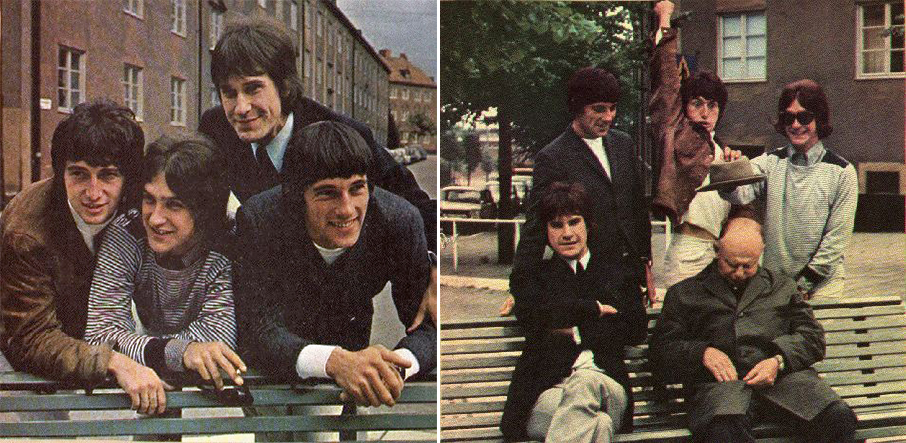

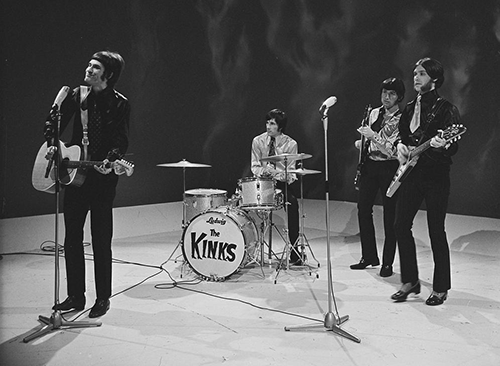

In 1964 a novice, kinkily-named British rock and roll band called the Kinks, formed by brothers Ray and David Davies, struggled mightily for recognition, a task made all the more difficult when teenage attention was hyper-focused on already established bands like the Dave Clark Five, the Turtles, the Yardbirds, the Rolling Stones, and the Beatles. Tough competition indeed.

The four-man Kinks made some headway when they scored a three-record deal with Pye Records.

Their first record managed to reach number 42 on the charts, enough to get the band a place on a rock-and-roll package tour of England and mention in the music trades.

The second single also flopped.

Pressure mounted. The third single on the Pye contract just had to be a winner.[1] A rock-and-roll band without a number one hit record was like a skiffle band without a tea chest bass. A miracle of some sort was needed, an intervention by the gods, but what?

As the group’s rhythm guitarist Ray Davies told Geoff Edgers of the Washington Post,

One day [in 1963] I saw this little green amp, like two doors down from where we lived. And [I bought it]. I had an argument with my girlfriend that day, and I was in a fit of rage and thought this amp didn’t sound right. So I got a razor blade. I slashed the cone speaker, and not knowing what I was doing at the time, didn’t even expect it to work. But I plugged it in and played and it sounded like a dog barking and I love it. We all grew to really love it and wrote this unusual kind of jazzy riff on the piano, which became “You Really Got Me,” and I started blasting it out through my little green amp. It seemed like everybody hated it when we were doing it, but when the record became No. 1 [in September 1964], everyone said: “Told you so.”[2]

Released in August 1964, the band's third single, “You Really Got Me,” went to number one on the UK singles chart and later in the year to number seven in the US charts.

All it took was a fit of rage, a slashed speaker cone, and a distorted sound from Davies’s little green amp.

Whether the guitarist or his girlfriend should receive the most credit for this happy musical accident is moot. Guitar distortion of this sort was old hat, invented (or discovered, if you will) more than a decade before in 1951.

That time, the speaker cone, rather than being slashed, was busted when someone accidentally dropped the amplifier on the ground.

On their way from Mississippi to Sun Studios in Memphis, Tennessee, to record their first record, Ike Turner’s band crammed themselves and two saxes, a guitar, and a drum set into a car when the inevitable flat tire happened. In their hurry to dig out the spare, they dropped the guitar amp on the pavement. Uh-oh.

Once they were at Sun Studios and meeting owner Sam Phillips—yes, that Sam Phillips, the one who nursed Elvis to worldwide acclaim—the guitarist plugged in his amp, and it sounded terrible, the speaker cone blown.

Sam pricked up his ears. It would sound different, he told the band, like another saxophone, and he went to the restaurant next door to score brown paper and wadded it inside the speaker.

Problem solved.

The rubbing sound between the saxophone and the distorted guitar in recording “Rocket 88” was instantaneous, the fuzztone taking the bass part, the horns riffing in unison, and Ike’s storming piano cutting through the churning mix.

No wonder “Rocket 88” became one of the most influential early R&B hits ever, as much for its exuberant drive as for its accidental fuzztone guitar that was copied by Chicago bluesmen who tampered with their speaker cones.

Later on, California guitarist Billy Strange used a fuzztone on his guitar. He did so on “I Just Don’t Understand” for Ann Margaret (1961) and on “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah” for Phil Spector (1962). And he did it the old-fashioned way by pulling one of the four 6L6GC vacuum tubes out of the back of his Fender Twin Reverb Amp.

Were the Davies brothers and the other Kinks totally unaware of this? The Beatles and the Rolling Stones were certainly aware. Paul McCartney used a fuzzbox—an early manufactured device called the tone bender—on his bass guitar on “Think for Yourself” on Rubber Soul (November 1965). Keith Richards used the early marketed Gibson Maestro Fuzztone on “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” (May 12, 1965).

What to make of all of this?

While the Kinks lagged behind introducing guitar distortion into their rock-and-roll mix, when they did, courtesy of an accident, it led to that coveted number one song followed by five top 10 singles in the US Billboard chart with nine of their albums charting in the top 40.

Today the Kinks are regarded as one of the most influential rock acts of the ’60s and early ’70s, and are ranked 65th on Rolling Stone's list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time.

For fans of that breakthrough song, Ray Davies later wrote a poignant origin story that he turned into a song “Little Green Amp” (2013).

CODA

Another lucky break, albeit a small one, came about with a change to the lyrics that helped the initial hit song’s appeal:

At the suggestion of [image consultant] Hal Carter, [Ray Davies] changed the initial address to the song, originally, he sang simply, “Yeah, you really got me,” but Carter urged him to toss in a girl’s name, any girl’s name, to address it personally to the listener. So Ray changed the lyric to “Girl, you really got me going”—changing the song from a vague fantasy to one of direct address.[3]

- Carey Fleiner, The Kinks: A Thoroughly English Phenomenon (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), 53–55.

- Geoff Edgers, “Q&A with Dave Davies,” The Washington Post, January 31, 2021.

- Fleiner, The Kinks, 54.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed