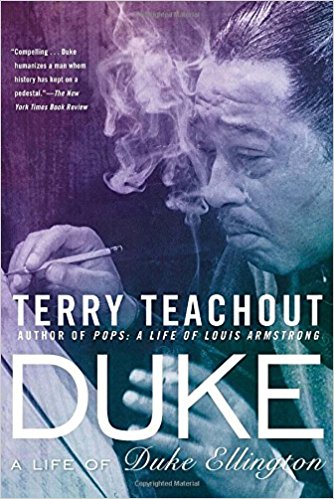

| In Ellington at the White House, 1969, I tender the view that Duke Ellington is America’s premier composer, not just the greatest jazz composer, a consensus view if there ever was one, but the greatest composer of any kind in the history of American music. Along comes critic Terry Teachout in his book Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington to challenge the absolute greatest view and raise the question of Ellington’s overall standing in the ranks of 20th-century American composers. Teachout takes aim at the maestro’s songs, as well as his longer and larger works: the concertos, suites, and programmatic pieces. |

And why did Duke do this? Not because he had the talent to recognize a good melody when he heard one, but because, as the Wall Street Journal critic implies, he was incapable of coming up with a good tune all by himself, simply not a “melodist.” In other words, Duke stockpiled other people’s melodies, much like comedian Milton Berle stockpiled other people’s jokes.

True, the inspiration of many Ellington songs came from others. Hence, according to Teachout, Ellington is a collaborative composer, a qualification that detracts from his status in comparison with other composers.

Here is the rub: For this re-categorization to hold, we can’t consider Ellington in isolation. We know a lot about the musical Ellington, but what about other composers? Where did they get their inspiration? From whom did they poach? And who did they collaborate with? Certainly with their lyricists, orchestrators, show directors, and producers. But to what extent?

Did George Gershwin and Richard Rodgers seclude themselves in underground, soundless caves, only to later emerge with their conjured musical phrases etched on stone tablets? Of course not.

To one degree or another, their melodies reflected aspects of the world around them in collaboration with other human beings. The process by which their tunes came about may not be as well known as Ellington’s. But it cannot be assumed that they did not draw from sources outside themselves. Teachout’s charge of radical Ellington collaboration is overblown.

I believe it is the maestro’s larger and longer works that separate him from most (if not all) of his fellow composers. Here, our intrepid critic is downright skeptical, dismissing Ellington’s early large-scale works Creole Rhapsody, Symphony in Black, Reminiscing in Tempo, Black, Brown and Beige, and Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue as inferior; referring to his theatrical efforts Jump for Joy, Beggar’s Holiday, A Drum Is a Woman, and My People as second-rate or worse; categorizing his late-career suites Such Sweet Thunder, Far East Suite, Latin American Suite, and the Afro-Eurasian Eclipse as no more than fitfully inspired, with few solos interesting enough to justify their length; and eschewing Ellington’s Sacred Concerts as lacking memorable themes.

Over the years, as Teachout documents, music critics have slammed Ellington’s masterworks as formless and shallow, aimless, less than unified, slight, not good enough, pretentious, and patchwork, as well as lacking indelible melodies, harmonic direction, and structural cohesion.

Teachout drags out all the disparaging remarks, and by not challenging them, the assumption can be drawn that he is endorsing them.

When the critics are not characterizing the maestro’s music as “floor show music for tourists,” they target his “mosaic” method of composition, which they see as a string of unrelated cameos, especially not suited for large-scale works bearing the name concerto or suite.

Teachout also singles out the mosaic composer’s penchant for falsifying true inspirations for songs and taking preexisting compositions and shoehorning them into fresh thematic works. It matters little at this remove that “Harlem Air Shaft” had nothing to do with life in a Harlem apartment, or that “The Star-Crossed Lovers” on Such Sweet Thunder had nothing to do with Shakespeare’s plays, or that “Isfahan,” on the Far East Suite, was originally named “Elf” before the orchestra even toured the Far East.

All this inside baseball stuff is interesting, but it doesn’t matter when you listen to Ellington’s music in 2018.

In conclusion, Teachout says, “The majority of Ellington’s critics agree that he was at his best in the forties,” and then quotes composer/conductor Gunther Schuller: “[Duke] never really understood the nature of the problem he was facing in undertaking to write in larger forms.”

Then Teachout states, “It is a verdict in which most scholars concur, though it does not diminish his stature in the least.”

Oh, yes it does, Mr. Teachout.

You may say Duke is still one of the greatest of composers of any kind in the history of American music, but by letting all the trash talk stand without challenging it one bit, it does diminish his stature.

Could anyone who has read your book, taken your conclusions at face value ever honestly believe that Ellington is America’s premier composer, outranking his Great American Songbook peers Harold Arlen, Irving Berlin, Hoagland Carmichael, George Gershwin, Jerome Kern, Cole Porter, and Richard Rodgers, among others? To say nothing of Eurocentric American composers like Aaron Copland or Charles Ives?

Could those readers believe that Duke even belongs in that elite Songbook group?

CODA

Numerous books have been written about the Great American Songbook composers, individually and collectively. None of these books has attempted to rank the various composers, perhaps out of respect for the individuals involved. Nonetheless, isn’t it about time for someone to conduct such a study involving a large number of experts? It would be welcomed, that’s for sure.

A model for such exists. Ten years ago, Hal Leonard published The Fifty Greatest Jazz Piano Players: Ranking, Analysis & Photos by Gene Rizzo. Setting aside both major and minor quibbles with that effort, the book remains a valuable reference. While open for debate, the number of composers considered should be less than 50, preferably less than 15.

The biggest hurdle to overcome is the number of experts and their identity (and secondarily, a funding mechanism for such an endeavor).

So who do you think is the greatest American composer? And who are the top 15? And why?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed