Four jazz icons came to prominence that year. Record bins overflowed with numerous recordings that would become enduring jazz classics. Public awareness of jazz was near an all-time high due to the notoriety of the beatnik jazz subculture, the popularity of West Coast jazz, and the musicality of household-name jazz musicians like Basie, Brubeck, Ellington, Fitzgerald, Getz, Shearing, and Sinatra.

And jazz was big business for the first time since the 1930s.

Four icons—Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Thelonius Monk, and Ornette Coleman—came to the fore in 1958, each to a different degree of public recognition and critical acclaim. They not only changed the direction of jazz forever but now rank among the handful of true jazz innovators who preceded them: Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Coleman Hawkins, Earl Hines, Jelly Roll Morton, Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, and Lester Young, to name the most prominent.

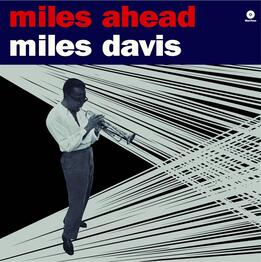

MILES AHEAD . . . WAY AHEAD

First and foremost, 1958 was the year of trumpeter Miles Davis. Record bins were filled by his prodigious output since his return to jazz in 1954, including his second full-scale masterpiece Walkin’. That album spawned the funky, hard bop jazz of the late 1950s and 1960s, much as his first masterpiece, Birth of the Cool, launched the “cool” West Coast jazz of the 1950s.

More importantly, record bins held the recorded work of his first great quintet: Paul Chambers (bass), John Coltrane (tenor saxophone), Red Garland (piano), Philly Joe Jones (drums), and, of course, Miles himself (trumpet). In terms of impact, these recordings—five albums in all—can be compared to Louis Armstrong’s classic small-group Hot Five and Hot Seven performances of the late 1920s. Miles’s quintet defined anew the potential for small-group jazz and expanded the emotional range from unbridled joy (Judy Garland) to fierce drive (Coltrane) to alternating complex sorrow and crisp rapture (Miles), often in the course of a single tune.

A collaboration between Miles and arranger Gil Evans, Miles Ahead featured the gentle lyricism of Miles on flugelhorn supported by a symphonic brass and reed choir. Miles’s use of the flugelhorn not only introduced a new sound to jazz but also rescued that instrument from the relative obscurity of marching bands. The album received the equivalent of a Grammy Award in France and an excellent five-star rating in DownBeat, the premier US jazz magazine of the day.

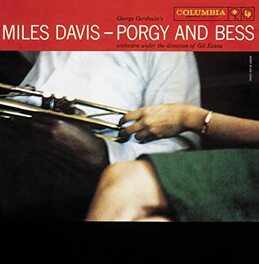

In late 1958, Columbia released the second Davis/Evans collaboration: a magnificent orchestral version of George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. Like Miles Ahead, Porgy and Bess featured a sustained dialog between Miles and the orchestra. Unlike the previous album, it exhibited a wider emotional range with Miles more dominant, partly because of his use of trumpet. It, too, received a five-star award in DownBeat.

Miles and Gil joined forces again on Sketches of Spain and Quiet Nights, but only Spain would maintain the excellence of Miles Ahead and Porgy and Bess. The Davis/Evans collaborations stand out as major contributions to 20th-century music, almost on a par with the classic small-group performances of Miles's first great quintet. His place in the jazz pantheon would have been assured on the basis of the quintet recordings and the orchestral collaborations with Gil Evans. But Miles had just begun.

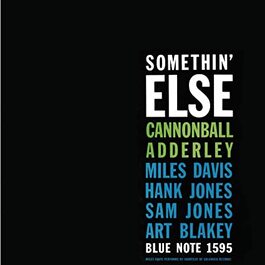

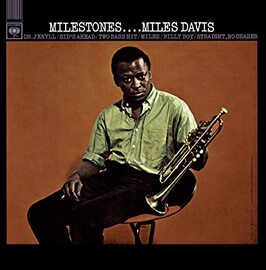

In mid-1958, Miles formed his first great sextet by adding Adderley to his quintet lineup. The group recorded Milestones and again opened up new musical territory, basing certain tunes and improvisations on modes and scales instead of on the song-form harmonic sequences that had been the favored approach for most jazzmen in the 1940s and 1950s. This time, DownBeat awarded Milestones only four stars.

Soon after Milestones, Miles replaced Red Garland with the introspective Bill Evans on piano and Philly Joe Jones with Billy Cobb on drums and produced the second great sextet. This group played at clubs and concerts throughout 1958 and recorded Kind of Blue in early 1959—one of the most celebrated albums in jazz history. The album expanded on the modal approach first revealed on Milestones and emphasized melodic over harmonic variation. Blue received almost instant universal acclaim and once again brought Miles a five-star award in DownBeat.

Without doubt, 1958 was Miles’s year, creatively, critically, and publicly. He emerged from the jazz underground onto the national scene as the year began with a feature story in Time magazine, a clear sign that Miles had arrived.

In midyear, Life International listed Miles as one of the 14 Black people who had achieved a stature of greatness. At year’s end, he had won first place in the DownBeat Critics and Readers Polls on trumpet and shared Jazzman of the Year honors with Count Basie. With general public recognition came financial recognition as well. He commanded concert and club fees comparable to only a handful of jazzmen—Dave Brubeck, Erroll Garner, and Chico Hamilton—while his albums sold at five to 10 times the norm for jazz.

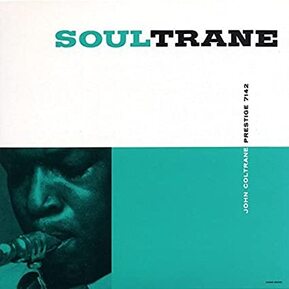

COLTRANE BREAKS THE SOUND BARRIER

The year 1958 was also good for another jazz icon, John Coltrane. While critical acclaim for Coltrane was not universal—there was even hostility in some quarters—and public recognition years off, Coltrane emerged that year as a new force on the tenor saxophone.

Some saw Coltrane, a key member of the great quintet and sextets, as riding Miles’s coattails to undeserved prominence. But others saw something new in his tenor playing: an extension of Coleman Hawkins, perhaps, but somehow different. Coltrane thought in sixteenth notes, while most players—and critics—thought in eighth notes.

They typically said his playing on Miles’s albums flawed otherwise perfect recordings. One critic said of Milestones, “Coltrane records material best left in the practice room.” DownBeat’s reviewer of the Newport Jazz Festival that year claimed Miles was hampered by the “angry young tenor” of Coltrane, another label that stuck. The DownBeat Critics Poll at midyear placed him fifth, behind fellow tenorists Stan Getz, Sonny Rollins, and Ben Webster.

The negative criticism continued into the 1960s, some reviewers arguing that his playing was “anti-jazz.” But after Coltrane picked up the soprano saxophone and recorded “My Favorite Things” in late 1960—rescuing that instrument from obscurity as Miles had rescued the flugelhorn—and recorded A Love Supreme in 1964, critical opinion turned mostly positive.

Coltrane’s playing continued to evolve amid controversy until his untimely death in 1967. As is so often the case, only after his death were his contributions to jazz seen as truly revolutionary. While never enjoying the same broad public acceptance as Miles, Coltrane was viewed as an inspirational leader for his uncompromising dedication to his art.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed