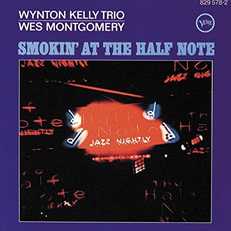

Interestingly, that same year, Wes recorded what many believe to be his best jazz album ever, the now-classic Smokin’ at the Half Note with the Wynton Kelly trio (Miles Davis’s rhythm section at the time). From the opening thirteen-minute “No Blues” to “Unit 7” to “Four on Six,” the Kelly trio mirrored Montgomery’s insistent drive throughout. Smokin’ indeed!

The latter album was but prelude to jazz top sellers Forest Flower and Love In.

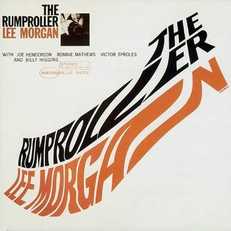

Many considered Rump a solid jazz album, but not the hoped-for chart-topper like the earlier funk buster.

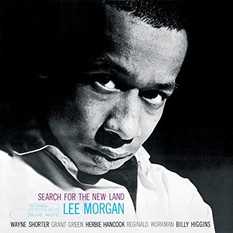

Nonetheless, an excellent record with an outstanding cast: Wayne Shorter (ts). Herbie Hancock (p), Grant Green (g), Reggie Workman (b), and Billy Higgins (dms).

An excellent outing with exotic touches.

In turn, the Duke issued his Concert of Sacred Music, recorded live at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco. The maestro’s return to long-form composition was applauded by many in the jazz arts community.

The Modern Jazz Quartet countered with Blues at Carnegie Hall, putting to rest all that nonsense about the group corseting jazz and smothering bebop with their more formally structured pieces (fugues, rondos, concertos).

When they wanted to, as in this eight-blues set, the boys could swing their asses off, pure and simple.

| Lastly, two sidemen from Miles’s second great quintet (not yet named as such) recorded now classic albums under their own name: Speak No Evil by saxist Wayne Shorter and Maiden Voyage by pianist Herbie Hancock. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed