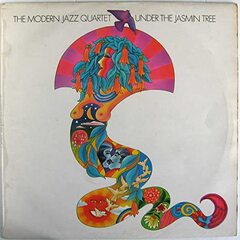

Newport All-Stars play in the Old Senate Office Building in Washington, DC, on June 18, 1962. From left: Ruby Braff (trumpet), George Wein (piano), Billy Taylor (bass), Marshall Brown (trombone), Senator Claiborne Pell, Pee Wee Russell (clarinet), and Eddie Phyfe (drums). (AP Photo)

Newport All-Stars play in the Old Senate Office Building in Washington, DC, on June 18, 1962. From left: Ruby Braff (trumpet), George Wein (piano), Billy Taylor (bass), Marshall Brown (trombone), Senator Claiborne Pell, Pee Wee Russell (clarinet), and Eddie Phyfe (drums). (AP Photo)

In a previous blog, I discussed a jazz concert sponsored by the Kennedy White House that was held at the Sylvan Theater on the Washington Monument grounds on the night of August 28, 1962. A gathering of mostly government summer interns heard the classic Brubeck Quartet followed by singer Tony Bennett and his trio. Columbia Records, with prominent producer Teo Macero on hand, recorded the music and belatedly released Bennett/Brubeck: The White House Sessions, Live 1962, on Columbia CD in 2013.

But surprise, surprise, there was another jazz group on the bill that night—the Newport All-Stars—led by jazz festival impresario and pianist George Wein. In fact, they opened the show, and Columbia recorded them as well but did not release the music. The sounds the interns heard that balmy summer night are now available to the public, thanks to the staff at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC (more on this later).

A swing Dixie outfit, the Newport All-Stars had been in existence since 1956 under the tutelage of George Wein. Over the years, numerous talented musicians have cycled on and off the roster. But during the 1958–1963 period, the core slots remained rather stable: George Wein (piano), Pee Wee Russell (clarinet), Ruby Braff (cornet), and Marshall Brown (valve trombone), supported by a pickup bassist and drummer, as was the case for the Kennedy-sponsored gig.

At the time, according to New Yorker critic Whitney Balliett, Wein’s group represented a type of jazz that was rapidly disappearing—relaxed, emotional, unpretentious, and of no school, firming the heart and brightening the eye.[1]

Pianist Wein was a swing stylist somewhere between Fats Waller and Teddy Wilson (Balliett again), though still comfortable in a bebop setting. His playing always amazed and exceeded expectations, especially for one burdened with the managerial complexities associated with staging festivals.

Clarinetist Pee Wee Russell’s playing was, well, a poet’s delight. From Balliett: “hopefully eccentric, squeaks, coppery tone, querulousness, growls, and overall hesitancy—most original stylist in jazz.”[2] And from another, writer/pianist Dick Wellstood, “crabbed, chocked, knotted tangle of squawks with which he could create such woodsy freedoms, such an enormous roomy private universe.” Nonetheless, all would agree that Pee Wee Russell could also coax pure and gentle notes from his instrument when he wanted to.[3]

Cornetist Braff took a pre-Bebop approach to improvisation, perhaps using more embellishment and vibrato than modernists, similar to his idol Louis Armstrong. Overall, he was a relaxed melodist, unique like his frontline companion, and should have been much better known.

Trombonist Brown had earned his festival wings with Wein back in 1958, when he worked his tail off to form the International Youth Band, which performed at Newport. The venture ultimately failed, done in by too many negative critical reviews. A later attempt at establishing a youth band made up of American high school kids succeeded, thereby reinforcing his exemplary leadership and teaching skills.[4]

As a trombonist, Brown never ranked at the top of the jazz polls, his reputation based on being a solid ensemble player. Wein once commented, “Marshall played decent valve trombone, although he never really had a trombone lip.”[5]

The rhythm section for the Kennedy gig consisted of Washington, DC, natives Billy Taylor Jr. on bass—yes, the son of famous pianist Billy Taylor—and Eddie Phyfe on drums.

The evening’s mostly youthful audience may not have been familiar with the Newport All-Stars and their brand of “rapidly disappearing” jazz. Their appearance occurred largely because three months prior, Rhode Island Senator Claiborne Pell, a former Newport Jazz Festival board member, invited the All-Stars to play a concert in the rotunda of the old Senate Office Building in Washington, DC.

The All-Stars played a lunch-hour show on Monday June 18 to some 500 senatorial staff members. It was the first such concert in the rotunda; the occasion was noteworthy enough to prompt the distribution of an AP Wire Service photo across the country. The next morning the All-Stars appeared on the NBC Today Show[6], and the Washington Post featured a front-page photo with the following caption:

|

Joint’s Jumping on the “Hill.” Sen. Claiborne Pell yesterday was host to the Newport Jazz Festival All-Stars, who conducted a jam session in the rotunda of the Old Senate Office Building. The visit here, which also included a concert last night for the Senate Staff Club, was designed to call attention to the annual Newport Jazz Festival, scheduled for July 6, 7, and 8 at Newport, R.I. In this picture, drummer Eddie Phyfe and bass player Billie Taylor [Jr.] swing out on a hot Dixieland number.[7]

|

The remainder of July and early August, Wein busied himself with establishing the inaugural Ohio Valley Jazz Festival outside Cincinnati, and on the festival’s last day, August 26, he joined the All-Stars on stage.[8] Two days later, after opening remarks by Rhode Island’s tireless Senator Pell, the band mounted the Sylvan Theater stage to perform for hundreds of summer interns (some with their parents) gathered on the Washington Monument grounds.

The band played six tunes, a well-paced mix of swing-era standards, four up tempo, one change of pace, and a Pee Wee special. Wein announced the title of each tune:

|

Up “Undecided” (1938): 5 min.

Up “Indiana” (1917): 6 min. “Blue and Sentimental” (1938):3 min. Up “Crazy About My Baby” (1929): 4 min. “Pee Wee’s Blues” (1930): 4 min. Up “Saint Louis Blues” (1914): 6 min. |

Applause from the largely student audience was respectful—if not overly generous—after individual solos and at the conclusion of a song, and then at the close of “Pee Wee’s Blues,” it was lengthy and loud, no doubt helped along by George Wein’s initial setup that promised a historic moment: “Pee Wee’s going to play the blues on the Washington Monuments grounds!” Drummer Eddie Phyfe also drew a huge ovation at the finish of his drum break on “Saint Louis Blues.”[9]

Thanks to the splendid work of Library of Congress staff, especially Bryan Cordell of the Music Division (Recorded Sound), the Newport All-Stars segment once lost has now been found. The entire Kennedy White House 1962 Sylvan Theater concert can now be heard at the Library.

As previously mentioned, fans can listen to the Bennett/Brubeck segments on a Columbia CD. Additionally, George Wein and the core group recorded in studio on October 12, 1962, which is available on George Wein & the Newport All-Stars LP/CD (Impulse).

There were only two Kennedy White House jazz events, the one described above and the other by the Paul Winter sextet for 10- to 19-year-old children of diplomats and government officials held in the East Room on November 19, 1962.

Interestingly, we have the music for both concerts, the former on Columbia CD (Bennett/Brubeck) and at the Library of Congress (Newport All-Stars), and for the latter, on Living Music CD (Paul Winter Sextet, Count Me In, 1962 & 1963).

There was only one other White House jazz event for which we have the music: President Nixon’s birthday extravaganza for Duke Ellington in the East Room on Blue Note CD: 1969 All-Star Tribute to Duke Ellington.

And that’s that!

How about all the other jazz events? For Presidents Johnson, Ford, Carter, Reagan, and the others? Isn’t it about time the music at the People’s House (as George Washington called it) is released to the people?

- Whitney Balliett, Collected Works: A Journal of Jazz, 1954–2001 (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2002), 174.

- Ibid., 76–77.

- Robert Hilbert, Pee Wee Russell: The Life of a Jazzman (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), xiii.

- George Wein with Nate Chinnen, Myself Among Others: A Life in Music (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2004), 184–86; 194.

- Ibid., 183.

- Ibid., 233.

- Photo caption “Joint’s Jumping on the ‘Hill,’” photographer Vic Casamento, Washington Post, Monday, June 18, 1962, page 1.

- George Wein, Myself Among Others, 432–35; Robert Hilbert, Pee Wee Russell, 241.

- George Wein comments, tunes played, and crowd reaction transcribed by the author from the audio: White House Jazz Seminar, Sylvan Theater, White House, 1962-08-28 (digital ID: 2603586), Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed