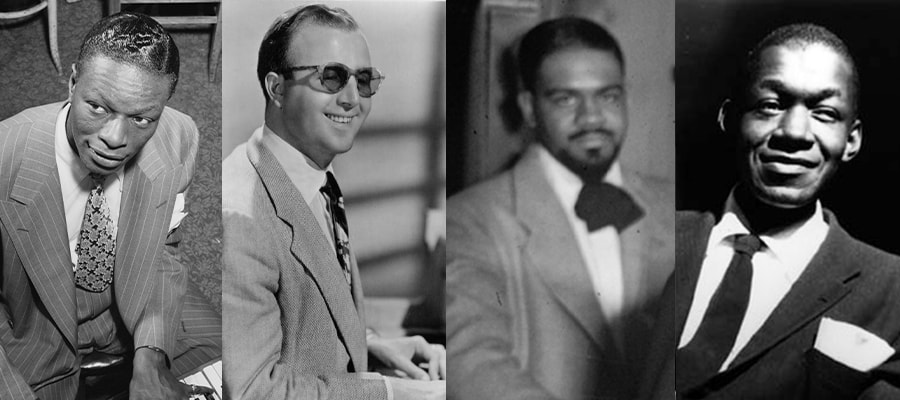

Herbie Nichols, Al McKibbon, Israel Crosby, Snooky Young, Buddy Morrow, Nat King Cole, Mercer Ellington, Lennie Tristano, Benny Harris, Ella Johnson, George Shearing, Art Blakey, Anita O’Day, Hall Singer, Babs Gonzales.[1]

Below, I spotlight four jazz legends from this group.

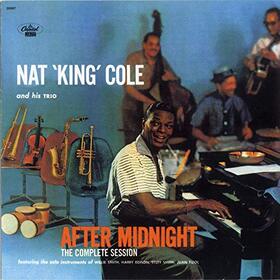

Nat King Cole

In the June 2004 issue of DownBeat magazine, a diverse group of 73 jazz singers (21 men, 52 women) were asked to name their top all-time favorite jazz vocal albums. The top 30 were listed; Midnight placed 12th. (Johnny Hartman and Frank Sinatra, the only higher-placed male singer albums, 2nd and 6th, respectively).[2]

[Nat and [his pal, trumpeter Harry “Sweets“ Edison] were at a [Dodgers baseball] game in August 1956 and they were overjoyed when [their] team . . . won, so much so that they had to let off steam by playing. Four calls were then made, first to Cole’s producer Lee Gillette to arrange for studio time at the Capitol Tower, and then to three regular members of his working trio, guitarist John Collins, bassist Charlie Harris, and drummer Lee Young. Upon arrival at the tower, Cole, Edison, and the trio quickly and exuberantly laid down five masters on songs they already knew very well.[3]

The songs had been previously recorded in other contexts, of course, and here they were expanded with more and longer solos—jam session style—exactly what Cole wanted. Nat and producer Gillette were delighted with the results and decided to turn the pianist’s impromptu jam into an album project—12 more songs over three more sessions, each with a different guest soloist.

Next up, Willie Smith, a swing era alto saxophonist second only to Duke’s Johnny Hodges. For this session, Cole edged off his jam session perch a touch and recorded newer material: “Don’t Let It Go to Your Head,” “You’re Lookin’ at Me,” and “I Was a Little Too Lonely (And You Were a Little Too Late),” the latter written by Ray Evans and Jay Livingston, the tuner pair responsible for Nat’s breakout hit “Mona Lisa.” The session ended on a jam session favorite with Nat and Willie stretching out on a finger-snapping “Just You, Just Me.”

For the third session, Cole wanted a Latin tinge and brought in Cuban percussionist Jack Constanzo and Ellington boneman Juan Tizol, composer of “Caravan,” which they dutifully played and followed it with the perfect companion piece “The Lonely One.”

Constanzo sat out while Cole and Tizol delivered the best slow ballads on the album: “Blame It on My Youth” and “What Is There to Say.” Freidwald rhapsodized: “Cole has never been more convincingly romantic, and he’s brilliantly supported by both Tizol and his own piano playing. As an interpreter of great love lyrics, the King takes a royal back seat to no one.”

The last session’s four tracks featured the “sainted collaboration” (Friedwald’s term) of Nat with grand swing era violinist Stuff Smith. They teamed up on a laid-back “Some-times I’m Happy,” “I Know That You Know” at race-horse tempo, with ripping piano-violin exchanges, a moderately swinging “When I Grow Too Old to Dream,” and a relaxed treatment of “Two Loves Have I.”

At the time of its first release, Midnight was a one-of-a-kind album, and it has remained as such. Nat King Cole never worked with a small jazz combo of that variety again.

CODA

Comments accompanying the Midnight 12th-place finish:

Grady Tate: “We know he is a genius at the piano but what he does vocally is unbelievable. One can understand each and every word he sings and the phrasing is impeccable. Nat set such a high standard for male singers.”

Tuey Connell: “The juxtaposition of the bop-leaning piano playing and his conversational delivery entices and challenges the listener at the same time.”

John Pizzarelli: “An amazing combination of spontaneity and arrangement. Everybody’s contribution from Lee Young’s drumming and John Collin’s guitar to Sweet Edison’s trumpet and Stuff Smith’s swinging violin perfectly compliment Nat’s swinging ease.”

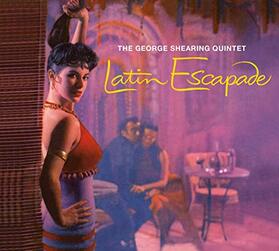

George Shearing/Al McKibbon

During WWII, Shearing met American jazz musicians (e.g., Fats Waller, Coleman Hawkins) while they were touring. They assured him of great success in the US. George crossed the pond to New York City, where he began to attract attention on the beboppin’ 52nd Street.

Gene Rizzo, author of The Fifty Greatest Jazz Pianists of All Time—who ranked Shearing ninth—continued the story from there:

In ’49, Shearing formed his famous quintet–a unique blend at the time of piano, vibes [Marjorie Hyams], guitar [Chuck Wayne], bass [John Levy], and drums [Denzil Best]. It became one of jazz’s biggest attractions. The quintet’s tight arrangements were based on the locked-hands style of Lionel Hampton’s pianist, Milt Buckner. Its formula, easily atomized, but less easily executed at fast tempos, featured the piano voiced in four-part chords. The right hand’s top, or melody voice, was doubled by the left hand within an octave. The vibes played in unison with the upper melody, the guitar with the lower.[4]

The initial lineup responsible for the unique “Shearing Sound” recorded for Discovery, Savoy, and MGM. The result—the nigh impossible—a hit jazz record: the immensely popular “September in the Rain,” which sold over 900,000 copies![5] Other not-as-popular singles followed, “I Remember April,” for example.

George continued to soak up the sounds of bebop piano masters Bud Powell and Hank Jones, and the newly arrived Latin rhythms (Latin jazz). He got his first taste of Latin music at the Club Clique in midtown Manhattan when he played opposite the Machito orchestra. He later reminisced: “The sounds were incredible, the rhythm complex, the bass lines were so interesting. I wanted to record Latin music, but the opportunity did not appear until I met bassist Al McKibbon, who knew the roots of Afro-Cuban music.”[6]

Detroit-born Al McKibbon—who shared the same birth year with Shearing—moved to New York in the 1940s. In 1947 he joined Dizzy Gillespie’s big band and played with Cuban percussionist Chano Pozo. Al learned the fundamentals of Afro-Cuban drumming from Pozo and played on the original recording of Dizzy’s “Manteca.”

Later he participated in the recording Birth of the Cool with Miles Davis. Particularly adept at blending Latin rhythms with straight jazz, McKibbon was at the heart of the Shearing Quintet from 1951 to 1958.[7]

In September 1953, the George Shearing Quintet, which now included Cal Tjader on vibes, Belgian-born ”Toots” Theilemann on guitar, Bill Clark on drums, Al McKibbon on bass, Catalino Rulon on maracas, and Candido Camero on bongos, recorded an album for MGM. Shearing was not pleased with his piano performance. McKibbon suggested he listen to the recordings of Noro Morales and Joe Loco so he could learn to ad-lib the Cuban montuno.

Shearing later said, “My ears became attuned to the authentic Afro-Cuban music thanks to AL McKibbon, the Machito orchestra, and Armando Peraza and Willie Bobo.” It was the Afro-Cuban whisperer McKibbon who suggested Shearing hire Peraza, who was regarded as a true virtuoso, unequaled as a bongo player and capable of amazing solos on conga drums.

Peraza joined the Shearing band in 1953, an association that would last eleven years. McKibbon declared, “When Armando came into the band, that was a new day.”[8]

Indeed, as Peraza later recalled:

I used to sit down with Shearing and sing melodies to him. He would play them on the piano and develop an arrangement. He was blind but he could see my ideas, my dream. Shearing said he loved my harmonic concepts. He allowed me to compose, to create.[9]

These albums contributed to the general acceptance of the music, along with the quintet’s appearances at jazz clubs, supper clubs, college campuses, and spaces generally off-limits to other jazz groups.

Between 1956 and 1963, I attended five shows: three in Cleveland, Ohio (two at the Modern Jazz Club, one at Public Hall) and two in Columbus, Ohio (one at the Kontiki Polynesian Restaurant, the other at a downtown hotel). Each set featured a Latin segment with Armando Peraza front and center.

Besides being an outstanding classical and bebop-influenced jazz pianist and the leader of an instantly recognizable, one-of-a-kind jazz quintet, George Shearing deserves plaudits for his early contribution to, and promotion of, Latin jazz, a genre that would attain significant popular status in the 1960s and beyond.

Herbie Nichols

A belated shout-out to a most deserving pianist-composer: Herbie Nichols. Jazz critic Gary Giddins writes:

[While] an incontestably modern and unique voice, and despite his own fabled persistence, he was only able to document four tunes for Savoy (1952), two albums for Blue Note (1955–56), and one for Bethlehem (1957) . . . He wrote over a hundred songs, but only 30 were recorded by himself, another three by Mary Lou Williams, and one by Billie Holiday.[11]

Pianist Frank Kimbrough marveled: “It’s bizarre. He wrote twice as many tunes as Thelonious Monk, yet he’s always been famous for being unknown.”

Well, perhaps not so much now. Nichols was inducted into the DownBeat Hall of Fame in 2017, more than five decades after his death from leukemia.[12]

- Jazz Birthday Calendar, 1919.

- Frank-John Hadley, “30 All-Time Favorite Jazz Vocal Recordings,” DownBeat magazine, June 2004, 48.

- Will Friedwald, The Great Jazz and Pop Vocal Albums (New York: Pantheon Books, 2017), 69–75.

- Gene Rizzo, The Fifty Greatest Jazz Pianists of All Time (Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2005), 35–36. See also additional confirming source: Len Lyons, The Great Jazz Pianists: Speaking of Their Lives and Music (New York: Quill, 1983), 98–100.

- Raul Fernadez, Latin Jazz: The Perfect Combination (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2002), 82.

- Ibid., 83.

- Ibid., 82–85.

- Ibid., 83, 77, 82.

- Ibid., 76.

- Ibid., 82.

- Liner Notes, Gary Giddins, Herbie Nichols--The Bethlehem Years, Bethlehem Records, LP, BCP 6026, 1976.

- Herbie Nichols, “Rightful Honor,” DownBeat Magazine, August 2017, 36.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed