Saxophone/flute player Charles Lloyd burst onto the California jazz scene in the mid-1960s on the strength of (1) albums Dreamweaver (1966) and Forest Flower (1967) featuring his first great quartet Keith Jarrett (piano), Cecil McBee (bass), and Jack DeJohnette (drums), and (2) the group’s appearances at Bill Graham's youth-filled Fillmore clubs.

After several years of pop adulation Lloyd entered into a period of (what should we call it) semi-retirement.

Lloyd’s real resurgence began in the 1990s when he signed onto the ECM label, recording sixteen albums with them followed by a stint with Blue Note into 2020, recording five albums.

The bulk of these albums feature Lloyd’s second great quartet (also known as the new quartet) Jason Moran (piano), Reuben Rogers (bass), and Eric Harland (drums). The best of which, in my opinion, is the highly entertaining Passin’ Thru (2017).

The album opens with Lloyd’s composition “Dreamweaver,” also recorded by his first quartet. The second quartet’s take is longer (by six minutes) and more complex, as Tom Jurek wrote:

"The version commences with a modal, post-Coltrane intro as the saxophonist explores tones and space before the drummer Harland checks into its groove, one that touches on the blues, folk music, a pop-style chorus and gospel before moving off to explore Eastern modalities, post-bop, and (some) dissonances before circling back to its lovely melody."

The following tracks reflect the various genres and styles mentioned above, singularly and collectively.

“Nu Blues” is a be-boppin’ swinger by the Jason Moran Bop Trio. Moran is rollin’ the keys like Bud Powell, Rogers is Ray Brown or Oscar Pettiford walkin’ the bass, and Harland is bebop originator Kenny Clarke keepin’ time on his ride cymbal, kickin’ the bass drum, and adding his own polyrhythmic textures. Tenorman Lloyd joins the Trio and its throwback time to a 1950s Norman Granz Jazz at the Philharmonic concert battlin’ it out with Flip Phillips and Illinois Jacquet.

Well, that’s the way I heard it.

“How Can I Tell You” is about as close the new quartet could get to a late-night slow dance dreamy ballad. Moran’s (almost) cocktail piano and the drummer’s use of brushes sets the mood for the leader’s lyrical saxophone offering to the song’s inspiration, singer Billie Holiday.

On “Tagor” Lloyd stirs the bluesy stew prepared by his rhythm mates with his Eastern sounding flute. At the start Moran strums the piano strings like a guitar, Rogers adds a Motown melodic bass line, and the drummer drives “Tagor” forward with a snare and hi-hat attack.

At the mid-point, with no loss of drive, Moran moves to the keyboard to pound out a funky chording interval over a rock-and-roll backbeat. Start to finish this is a hand-clapper.

The title track opens with unaccompanied bass and then, boom!, the band takes off with a high energy up-tempo dance-like excursion into bop. Moran’s piano and Lloyd’s tenor solo engage Roger’s and Harland’s rhythms with startling athletic lyricism.

Bordering on playful and/or novelty, “Passin’ Thru” is a crowd pleasin’ groove.

The album closes on a respectful note with “Shiva’s Prayer.” A beautiful unaccompanied piano piece by Moran, with lovely arco bass playing by Rogers, and soft drums by Harland.

Then quiet.

Scott Yanow in his ultimate guide to the great jazz guitarists opined, "Sonny Sharrock was the first truly avant-garde guitarist in jazz. . . When Sharrock burst on the scene in the mid-1960s, he was not only free in his choice of notes but in . . . his use of feedback and distorted sounds. He preceded Derek Bailey and Jimi Hendrix. During an era when few jazz guitarists even acknowledged rock, Sharrock was playing explosive solos that made him the Pharoah Sanders of the guitar.”

Interesting, then, that he would pair up with saxophonist Sanders, along with bass player Charrette Moffet and drummer Elvin Jones in 1991 to record Ask the Ages, the consensus definitive and most essential album of Sharrock’s career.

This is unquestionably a free jazz album, how could it not be with Sonny Sharrock, Pharoah Sanders, and Elvin Jones ripping it up as if it was 1965.

Yet it is something else again, appealing and accessible to a wide range of music fans. Proof of this can be found on google: type in “rateyourmusic.com Ask the Ages,” select the top entry, and read the 45 reviews, and you’ll see what I mean.

Ask the Ages has six original Sharrock compositions: two scorchers “Promises Kept” and “Many Mansions,” two mellow and melodic “Who Does She Hope to Be” and “Once Upon a Time,” and two in-betweeners, “Little Rock” and “As We Used to Sing.” It is the mellow tunes (and secondarily the in-betweeners) that make this album so appealing with “Who Does She Hope to Be” generally favored over “Once Upon a Time.”

But for my money, the latter is the exceptional track.

While each instrument is heard in “Once Upon a Time,” it is the collective daresay “symphonic” — like sound that matters.

Sonny’s guitar, chording Hendrix-like and soloing at the same time (dubbing may have been involved); Pharoah’s tenor sax, offering a repetitive hummable figure; and Elvin’s non-stop striking of his drums with mallets, yes, with mallets not sticks or hands, creating a rhythmically throbbing pattern. Occasionally, Sonny spices the group’s malleting stew with a memorable Santana-like guitar line.

Overall, a never-to-be forgotten, compelling track.

While Sinatra’s time capsule albums are Wee Small Hours in the Morning, Songs for Swinging Lovers, Only the Lonely, and a few others, the “Jazziest” is Frank Sinatra with the Red Norvo Quintet Live In Australia 1959.

A rare album where Frank sings his well-known fan favorites, not as originally recorded with a large studio orchestra, mind you, but backed by a small jazz combo live.

From Will Friedwall’s liner notes:

“He just melted into it . . . He took responsibility (like a conductor) he beat off the group and everything, he did his own thing, and the band played great for him . . . [Alto/flute] player Jerry Dodgion elaborated: the informal format also encouraged Sinatra to vary both the program and the arrangements themselves . . . He could be different every night which is more in keeping with a jazz group.”

For me, Ol’ Blue Eyes' best live album is Australia 1959.

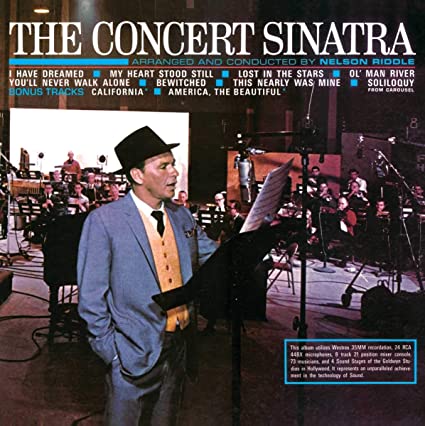

In the entire recording oeuvre of Frank Sinatra there is nothing like The Concert Sinatra, an album of extended performances by Frank and a 73-piece symphony orchestra arranged and conducted by Nelson Riddle.

The recording features eight tunes (lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein on all but one.) These are not the vocal offerings of familiar Sinatra poses, the finger-snappin’ swingin’ bachelor or the down-and-out sad sack propped against the lamppost.

No, this is the full-voiced light classicist in the manner of contemporaries Todd Duncan, Howard Keel, Gordan McRae, or (almost) Paul Robeson.

In other words, Frank gets as close as an American pop singer can to the bel canto style.

On no other album does Sinatra reveal such strength in his lower register and overall dynamic range. This album is in a class by itself. Discussions of what category it belongs to: jazz, pop jazz, pop, or Broadway — are irrelevant.

It’s simply incandescent.

No male interpretive singer of the 20th century other than Frank Sinatra could have pulled this off.

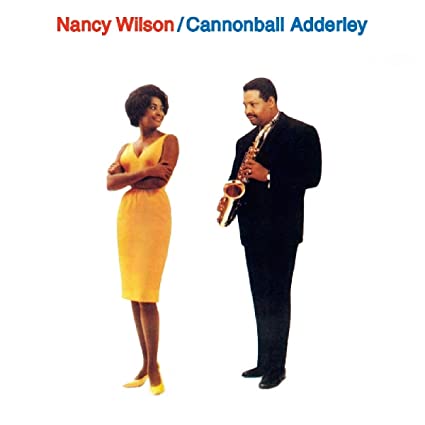

I bought this CD for two reasons: one, my fondness for the classic Adderley Quintet (Cannonball (Alto), brother Nat (Cornet), Sam Jones (Bass), and Louis Hayes (Drums) with Joe Zawinal (Piano); and two, my piqued curiosity after I read an article in Downbeat magazine in 2004, listing the best jazz vocalist albums chosen by 73 jazz singers (21 male, 52 female).[1] At the top, number one, was the album Nancy Wilson/Cannonball Adderley originally recorded in 1961.

After multiple listenings, I came around to understanding the record’s appeal to the Downbeat singers, helped along by Nancy Wilson’s statement in the album’s liner notes that she considered her vocals on the album “as a sort of easy-going third horn.”[2]

Jazz singers (all singers?) in particular desperately want to be a thoroughly integrated member of the band — not off to the side or out front, but in the mix. And that, in fact, was what Nancy was in this instance and what the DownBeat singers heard and no doubt wished for themselves.

The album is doubly interesting because it is not entirely a vocal album, five of the 12 tracks are instrumentals by the quintet (every one outstanding) especially Cannon’s alto solo on the trumpet warhorse “I Can’t Get Started” and the brothers cookin’ on “Teaneck,” but it is the seven Wilson tracks that caught the ears of the DownBeaters.

Highlights for me are the gentle cornet playing by Nat behind Wilson on “Save Your Love for Me” and Nat’s tune “The Old Country;” and Cannon’s bopish swinging sax duet with Nancy (and Nat) on “Never Will I Marry” and “Happy Talk.”

Sam Jones bass is superb, especially on “A Sleeping Bee.”

- “Singers” All-Time Favorite Vocal Jazz Albums, DownBeat, June 2004, 48.

- Ron Grevatt, original liner notes, Nancy Wilson/Cannonball Adderley, Capitol Records, 2004, Compact Disc, CDP 077778120421.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed