One thinks of Cannonball Adderley’s cover of the score for Jump for Joy (1), the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra’s many performances of Ellington-Strayhorn suites and thematic materials, including the Far East Suite (2) and recently, the Asian American Orchestra’s version of the Far East Suite, which earned a year 2000 Grammy nomination (3), and the Slovak Soul Party! (4) with its take on the one Ellington suite that would make nearly everyone’s top five (my number one).

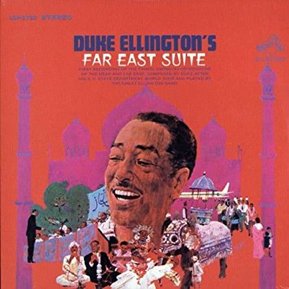

The suite’s inspiration was mostly influenced by the sights, sounds, and smells absorbed by Ellington and co-composer Billy Strayhorn during the band’s 11-week tour of South Asia and the Middle East in 1963, which afterward, as Duke later said, seeped out on paper for the band’s musicians to elucidate.

Tourist Point of View

IN FIVE evocative minutes, Ellington and Strayhorn were able to highlight all the orchestra’s important elements: the scorching trumpet of Cat Anderson; the well-matched burnishes of the trombone section; the burry, shaded timbre of Gonsalves’s juggernaut tenor, rising from the rich textures of the reed section; the unmistakable touch and prominent accents of Ellington’s piano; and the dark energy that characterized much of his later writing. (5)

Familiar yet intriguing, “Tourist” prepares the listener for more unusual things to come.

Blue Bird of Delhi (Mynah)

Isfahan

Hodge’s stiletto sharp, crystalline pure sound slows the breath, wells the eyes, and stills the body while Ellington’s orchestra puffs occasional sound pontoons to keep the alto’s melodic line afloat, mimicking to some extent, what arranger Gil Evans did for Miles Davis. If perfection needed a definition, it can be found here.

Depk

The piece opens with the reed section articulating the eminently whistle-able theme, then a mirroring by the brass, and a back-and-forth between the sections that leads to a short piano interlude by the maestro. The piece retraces it steps back to the reed section opening before the denouement, the thinning out, Hamilton-Carney by themselves, whistling the happy theme to a fade.

And how often, one wonders, has Ellington or anyone else for that matter, paired a high-register clarinet with a baritone sax so effectively?

Mount Harissa

Gonsalves to me has three voices: a lowing moan one hears on the “Tourist” opening and the R&B driving wail heard at Newport ’56 and another where he splits the difference between the two as heard here on “Mount Harissa.”

Others have called his sound snaky, smoky, or serpentine, but in all cases, a swinging, “please don’t stop” songful moan. His spotlight partner Duke deserves most of the credit, however, for both the composition (along with Billy Stayhorn) and his magnificent, incomparable piano work. In an album full of jewels, this one shines the brightest.

Blue Pepper (Far East of the Blues)

This Eastern-tinged melody gives way to the flipside of the Hodges coin, the bluesy side, but in this instance, a solo of clipped, start-and-stop notes that suggests rather than delineates. In other words, a near parody of a typical Hodges blues solo. And it works!

Enter high note trumpet specialist Cat Anderson. He takes his cue from the Rabbit (Hodges’s nickname) and sputters, squeaks and squeals over Speedy’s head-wagging, rock-steady groove. An absolute delight! And did anyone at the time think to release a 45 rpm single with “Pepper” on the A side and “Isfahan” on the B? It would have charted on college jukeboxes and radio stations for sure.

Agra

Duke’s desire to “take in a little more territory” to musically portray the torment felt by the imprisoned man led to Harry Carney’s languorous, weighty voice on baritone saxophone to plumb the depths of amorous despair.

The number could have equally been assigned to altoist Johnny Hodges—it is a lovely Billy Strayhorn melody after all—but the result would have been more sweepingly romantic, not when anguished unrequited love is called for.

As it stands, Carney delivers a performance to rival any of his ballad solos, including “Sophisticated Lady.”

Amad

The featured soloist, Lawrence Brown, mimics the high-pitched quivering Islamic call to prayer on his trombone, something he and the other members of the orchestra heard daily in many of the countries they visited.

Ad Lib on Nippon

Fugi

This is a piano trio number with Ellington sharing the spotlight with bassist John Lamb. To start, Duke picks out a spare, repeating seven-note melody, while Lamb plucks out well-placed bass notes.

This segment morphs into a lovely Dukish melody accompanied only by Lamb’s bowed bass. Duke next drops irregular dissonant chords as Lamb strums his bass like a koto (perhaps). The pair returns from whence it all began. A showcase for the musician’s talent, “Fugi” offers one delightful sound image after another.

Igoo

The trio kicks off a fast tempo swinger and the ensemble quickly follows. Sections trade the theme back and forth with trumpeter Cat Anderson sounding an exclamation point at end of each brass section statement.

Nagoya

Multi-stylistic pianist Ellington eschews his penchant for dissonance and taps a less-used keyboard style to sketch an uncommonly beautiful melody. Only John Lamb’s softly bowed bass disturbs the quiet. This one ranks up there with the maestro’s “A Single Petal of a Rose.”

Tokyo

This is an up-tempo vehicle for co-composer Jimmy Hamilton. Never sounding better on what must be his longest outing on record, he starts off with a short clarinet solo that evolves into a series of trills. The brass and reed sections return buttressing Hamilton’s pure-toned, full register improvisations for a rather lengthy workout. The woodwind master closes the piece, appropriately, without accompaniment.

Over the years, Ellington suites have come under attack by several critics for not being suites at all, the argument being that the themes introduced at the outset are not recapitulated or further developed.

See Terry Teachout’s book DUKE: A Life of Duke Ellington for a catalog of slights registered against Ellington compositions. (10) Kurt Gottstalk slammed the Far East Suite in particular, saying the nine pieces that make up the suite are scattered and lack an overriding theme—the concept is carried out in the titles more than the music. (11) Ouch!

Alan Bumstead reports that some critics have pointed to the fact that the Far East Suite does not actually work as a “suite” in a musical sense—the compositions are too varied to work as a part of the whole. (12)

Other critics see a coherent togetherness in the suite that others don’t. But it doesn’t matter. It is not a Eurocentric suite, it is an American jazz suite of the sort Ellington wrote all his life, one characterized by the unpredictable unfolding of different sound images one after the other.

The work as a whole is a beautiful piece of music, the tracks—I’ll call them that—seem to work together regardless of intent. The whole can be enjoyed just as it is, as itself, repeatedly. And that’s all that matters.

Still others have questioned the integrity of the suite from another angle—the fact that certain pieces were composed prior to the orchestra’s foreign trip, like “Isfahan” and a section of “Ad Lib on Nippon.” Ellington believed they belonged in the suite, and that’s good enough for me. A work’s creation story, no matter how fascinating, should not interfere with the enjoyment of the final result. The proof is in the pudding, and not in its various ingredients. Duke’s ambitious album won a Best of the Year award from DownBeat magazine and a Grammy for Best Large Jazz Ensemble. Some pudding!

- Julian Cannonball Adderley, Jump for Joy, 1959, Mercury MG 36146.

- The SMJO has performed at least 10: Such Sweet Thunder, Far East Suite, Queen’s Suite, Nutcracker, Degas Suite, Anatomy of a Murder, Black, Brown and Beige, Peer Gynt Suite, Personal Communication, Kenneth R. Kinnery, Program Director, Smithsonian Jazz, Washington, DC, September 1, 2016.

- Far East Suite, Anthony Brown’s Asian American Orchestra, CD Baby.

- Slavic Soul Party! Plays Duke Ellington’s Far East Suite, ropeadope, RAP-314.

- Neil Tesser, Duke Ellington’s Far East Suite, 1999.

- Richard Cook and Brian Morton, The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD, 7th edition (New York, Penguin Books, 2004), 502.

- Stanley Dance, East Meets West through the swinging music of Duke Ellington, original liner notes, Duke Ellington’s Far East Suite, Bluebird first editions 82876-55614-2.

- Ibid.

- THE FAR EAST SUITE: Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn Arrangements, eJazzlines, The Global Source for Jazz .

- Terry Teachout, DUKE: A Life of Duke Ellington (New York: Gotham Books, 2013).

- Kurt Gottschalk, “Duke Ellington: Far East Suite,” All About Jazz, 2004.

- Alan Bumstead, “Duke Ellington, Far East Suite, 1967,” 2011.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed