| In preparation for Duke Ellington’s 70th birthday tribute dinner at the White House in 1969, President Nixon asked the maestro to submit a list of people he would like to see invited. Ellington submitted 135 names, and the White House sent out invitations to all save one—Frank Sinatra (but that’s another blog). Five female singers were invited, but only Mahalia Jackson accepted. The gospel diva had crossed Duke’s career path in 1957 when she lent her talents to his reworking of the Black, Brown and Beige suite for Columbia Records. |

- Contralto Marion Anderson, who had known Duke for decades, and sat with him on President Nixon’s Advisory Council on the Arts

- Diahann Carroll, who starred in the 1961 film Paris Blues that Duke scored

- Leslie Uggams, who appeared with Duke on several televised variety shows

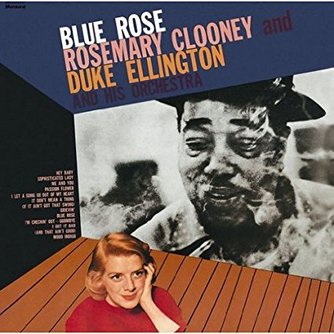

- Rosemary Clooney, who collaborated with Duke and the orchestra on the 1956 Columbia album Blue Rose

Clooney was the first singer not drawn from the ranks of the Ellington orchestra to cut a full album with the Duke. Only two other singers had that honor: Ella Fitzgerald and Frank Sinatra.

Moreover, the idea for the project came not from Ellington, but from Rosemary. She wanted to break free of her pop chains, and Duke needed a boost in association with a high-flying AM radio and TV variety show pop star. At the time (early 1956) the maestro wandered in a frozen wilderness of public apathy and needed a breakout. Blue Rose, he must have thought, could be the icebreaker.

As it would turn out, Blue Rose would be the first album ever to be overdubbed. Ellington recorded the orchestra tracks in New York, and Rosemary added her vocals in Los Angeles.

This technical first was necessitated by the fact the singer was severely pregnant and unable to fly to New York—which also meant that the album’s designated arranger, Billy Strayhorn, had to fly back and forth between New York and California to work with Rosemary on song selection, setting of keys and tempo, and other musical matters.

The material the two chose consisted of six Ellington standards—“Sophisticated Lady,” “I Let a Song Go out of My Heart,” “It Don’t Mean a Thing,” “I Got It Bad,” “Mood Indigo,“ and “Just Sittin’ and A-Rockin’"—and three lesser known Ellington-Srayhorn collaborations—“Grievin’” and “I’m Checkin’ Out-Goombye” (both from 1939) and “If You Were in My Place” (1938)—as well as three new Ellington tunes, one of which, “Blue Rose,” had no lyrics, but came with instructions: just scat along with it.

Prominent critics Will Friedwald and Gary Giddins had nothing but high praise for the album, the latter declaring “Sophisticated Lady” to be one of the finest recorded versions ever.

To my ears, however, the results are disappointing. Ms. Clooney, known for her sultry voice, is not sultry enough, sounding a mite tense and more like pop icon Dinah Shore than any jazz singer one could name.

Rosemary chose not to stamp her mark on the famed doo-wah doo-wah riff on “It Don’t Mean a Thing,” avoiding it altogether, leaving it to the instrumentalists. Her “ba-bee be-ba be-ba ba-ba” scatting on “Blue Rose” is amateurish, but Friedwald heard it differently, calling it “superlative.”

Nonetheless, one track, “Mood Indigo,” stands out, and could very well be one of the finest on record. Strayhorn rearranged the famous clarinet-trumpet-trombone-unison opening melody for Clooney’s wordless voice plus two trombones, which almost trumps the original.

As Ken Crossland and Malcolm MacFarlane opine in their biography Late Life Jazz: The Life and Career of Rosemary Clooney:

[While] mid-1950s sales of Blue Rose were unspectacular . . . its importance in the careers of both its protagonists cannot be overstated. For Ellington, it took him back to Columbia and opened the door for Ellington at Newport ’56, which became the best selling album of his career and launched a resurgence that sustained him until his death in 1974. [Hence, the delayed thank-you from Duke to Rosemary in the form of a White House invitation.]

For Rosemary, it convinced the girl singer from Maysville [Ohio] that she was more than just a chirruping hit-maker. The experience of working with Ellington, she said, “validated me as an American singer. My work would not fade with my generation. I had now moved into a very exclusive group. [As her many late-life Concord albums would attest.]

Perhaps I have been a little harsh in my assessment of the album in question. Take a listen to the recently released Blue Rose CD on the Columbia Legacy label, and you decide.

One thing everyone should be able to agree on is that somebody passed up a golden opportunity to have Rosemary—when her late-life jazz voice had fully developed—to re-record over the original Ellington tracks, assuming the tapes could have been found in the vaults, of course.

Now that would have been something.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed