Here, I look at the remaining half of my collection and discuss several of the singular, transcendent albums. They're listed in no particular order.

For Wes Montgomery, 1966 was a breakout year. The most influential jazz guitarist since Charlie Christian, Montgomery was known for his thumb plucking and innovative approach to playing two notes at the same time an octave apart.

Interestingly, the year Montgomery crossed over to the pop market with his R&B hit “Goin’ out of My Head,” he recorded what I (and many others) believe to be his best jazz album with the Wynton Kelly Trio (Miles Davis’s rhythm section at the time).

From the opening 13-minute “No Blues” to “Unit 7” to “Four on Six,” the Kelly Trio mirrored Montgomery’s insistent drive throughout. Smokin’ indeed!

Rollins surprised many with his 20-minute title track featuring his tenor and extracted mouthpiece, along with John Coltrane’s rhythm section bassist Jimmy Harrison and drummer Elvin Jones with trumpeter Freddie Hubbard (on one track).

At the time, many people thought Sonny was about to join “New Wave” pioneers Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry because of the use of just a mouthpiece. But, no, it was Rollins simply saying he could play free if he wanted to, and this was the way it should be done. I agreed, wishing he had done more of it.

Here is recorded proof that pianist Powell’s abilities were still intact well into the last decade of his life. Maybe not on a par with his superhuman playing of the 1940s, but mighty close.

This album presents the cream of his performances between 1959 and 1961, including a driving duet with expat tenor man Johnny Griffin on “Idaho” and “Perdido,” both of them grunting their own throaty comments as the music swirls and swoops. Bud, in a trio setting with bebop drummer Kenny Clarke, essays his own compositions—“John’s Abbey” and “Buttercup”—showcasing his firm touch and unceasing swing at both medium and up tempos. This is a historically significant album.

Kip Hanrahan, not exactly your well-known jazzer, has taken a rather eclectic approach to music, regularly assembling diverse groups of Latin, rock, folk, and jazz musicians (and poets) in the studio and recording them for his own American Clave label.

Conjure contains a track with a most unlikely title—“The Wardrobe Master of the Universe”—sung by folk artist Taj Mahal, a bouncy tune that received extensive airplay on my home stereo. The ensemble, with Carla Bley on piano, sets up an infectious Latin-popping groove from the get-go. After Mahal’s vocal, David Murray enters with the most concise R&B, jazz, funky avant bop solo imaginable, all over his horn top to bottom—that was obviously improvised, but so perfect you’d think it had been scored and then woodshedded for years!

Post-bop pianist Hawes recorded a lively set in Paris accompanied by the two expats Jimmy Woode (bass) and Arthur Taylor (drums). Two tracks stand out, the Hawes-composed jazz waltz “Sonara” and the lovely Richard Rodgers ballad “My Romance.” The former, buoyed by a loose and fluid rhythm section, is the most infectious jazz waltz ever recorded, bar none.

The lengthy “My Romance” is a Hawes favorite, a ballad that can be played as such or at a medium tempo. He does both here and even adds a ringing block chord segment. Simply gorgeous. There is, as far as I know, no better jazz piano instrumental treatment of this song.

The “Satch” and “Josh” are none other than Oscar Peterson and Count Basie. Two dissimilar pianists could not have been found on the planet to cut a duo record, backed by a superb rhythm section: Freddie Green (guitar), Ray Brown (bass), and Louis Bellson (drums).

Peterson’s technique is complex and prolific. Basie’s is simple and sparse. Peterson is arabesques, fluttering appoggiaturas, and grace notes, and Basie is bare bones. And does it ever work. Why? Despite differences, they both share an atomic sense of time and a fathomless understanding of the blues. In fact, 6 of the 10 songs on the album are jointly composed blues, and the rest are standards. A more delightful, one-of-a-kind record is not to be had.

Seldom in jazz history has a new jazz movement been so thoroughly documented as on the Wildflower series. Thirty-two performances by 60 new wave musicians were recorded at the loft home of saxophonist Sam Rivers over seven May nights in 1976.

The music resulted in five separately issued LPs played by a veritable who’s who that included Hamiett Bluiett, Charles Brackeen, Anthony Braxton, Marion Brown, Dave Burrell, Anthony Davis, Ola Dura, Julius Hemphill, Fred Hopkins, Oliver Lake, Byard Lancaster, George Lewis, Jimmy Lyons, Ken McIntyre, Roscoe Mitchell, David Murray, Sonny Murray, Sam Rivers, Henry Threadgill, and Abdul Wadud.

Please forgive the mostly unrecognizable name list—none were household names at the time, even in the jazz community. But that is the point here: this was the first assemblage of wildflowers intent on adding yet another branch to the growing jazz tree.

As percussionist Chano Poso was to Mario Bauza and Dizzy Gillespie, Armando Peraza was to pianist George Shearing on this historic latin jazz album. Peraza was featured on congas and other percussive instruments at every Shearing quintet performance for over 12 years.

My young jazz ears, tuned to odd time signatures and ethnic rhythms from the get-go (don’t know why), delighted in listening to the rhythmic sounds of Armando on this LP, as well as at five Shearing club performances I attended from 1955 to 1961.

Yet another time signature mash-up—the first time in history Western musicians (all from the UK by the way) and Indian musicians played together from a written score. Improvising by both sets of musicians took place, especially by alto player Joe Harriott, who played his own brand of free jazz.

Not all fans and critics took to the fusion, but I did. Maybe a little stilted at times, but always exciting and swinging. As Mayer proclaimed, “World Music began here,” and who is to say otherwise.

A trombonist most prominent in the ’50s and ’60s, Green was not really a skilled technician. He often relied on a satchel of repetitive licks, but what licks and what a sound, a blues-drenched Tommy Dorsey sound, less vibrato than Dorsey, with a smooth, high-register wail that split the differences between swing, R&B, and bebop. Though many of his albums are out of print, you can still find this early outing. No other like him, ever.

In the 1970s Gillespie hooked up with producer Norma Granz on his newly formed Pablo label. After several pairings with jazz masters from his era, Diz implored Granz to put aside all these “history” recordings and let him record something “modern.”

The result: Dizzy’s Party, a hip-shaking Latin jazz album for funk fans, with two electric guitars, drums, and Brazilian percussion to support trumpet and saxophone. Granz should have released a single from what he called Dizzy’s dance album. I saw the band twice, and it was a party.

The West Coast–based Counce group was one of the great quintets of the 1950s: Curtis on bass; the underrated Carl Perkins on piano; Frank Butler, the cleanest, most impeccable sounding drummer of the era; and two journeymen, Harold Land on tenor sax and Jack Sheldon on trumpet.

Bounce is their standout album. The best track: “Stranger in Paradise” from the Broadway show Kismet. The band never swung harder than on this medium tempo romp, but the standout solo belongs to Sheldon, who overcame his technical limitations (obvious on the other tracks) to produce a perfectly logical and memorable solo.

Had Sheldon played at this level consistently, he would have been a household jazz name, along with other notable middle-register trumpeters like Chet Baker, Miles Davis, and Art Farmer.

Here is yet another eclectic album where rock, pop, and jazz musicians pay tribute to Thelonius Monk. The Carla Bley track features her 15-piece big band with guest Johnny Griffin on tenor saxophone doing their version of Monk’s quirky “Mysterioso.”

The cut begins with the band in full force sounding like a tool and die shop clanking away at full capacity and melds into a gorgeous contrasting counter theme, a Johnny Griffin solo, a routine but faux ending, a piano trio interlude featuring Bley, and then the REAL ENDING, which is what makes this track so memorable—the band laying down sumptuous chords as Griffin soars up and down his instrument sounding like a baritone, tenor, and alto all rolled into one.

The finale makes me think of other rousing endings: Stravinski’s Sacre Du Temps and Mousorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition.

Most jazz fans haven’t heard of New York–based trumpeter Charles Sullivan. Few records to his name, that’s for sure, but on this one, there is a magical moment, a 30-second coda to “Now I’ll Sleep,” a song with a rather depressing lyric sung by a young Dee Dee Bridgewater.

As the song seemingly ends, the recording engineer switches to reverb (the click is heard), and Sullivan switches from trumpet to flugelhorn for a lilting improvised duet with Ms. Bridgewater. Dee Dee’s wordless vocal intertwines around Sullivan’s rich line, first mirroring then contrasting—like a double-helix strand of DNA.

On the same album, another magical duet, this time with pianist Onaje Allan Gumbs on “Good-Bye Sweet John,” a musical interlude repeated three times with increasing volume and bravura—a china-lovely chamber piece evoking simultaneous feelings of sadness and triumph. Countless times I’ve returned home, slapped on the disc, and dropped the needle to hear these two romantic snippets.

One of the first trombonists to explore free jazz, Moncur presided over a recording session with a to-die-for lineup: altoist Roscoe Mitchell, drummer Andrew Cyrille, pianist Dave Burrell, and tenor Archie Shepp. One track is transcendent, the 12-minute “When,” the reason why this album should be in every fan’s collection, whether a free jazz devotee or not.

After stating the riff-like theme, Moncur improvises variations on his riff before passing the baton to Mitchell, who in turn elaborates on the trombonist’s excursions. With his Texas R&B roots in mind, Shepp expertly weaves among his predecessor’s instrumental statements.

Excellent solos all, but what makes the frontline commentary delicious is the rhythmic underpinning: Burrell’s steady vamping piano and Cyrille’s churning cymbals produce a recognizable forward motion. In simpler words, this tune swings!

Several decades ago, I hosted a radio program for several months and my opening theme song was “When.”

In the second half of the 1970s, former President Carter, seeking a thaw in US-Cuban relations, sent jazz, rock, and salsa musicians to Cuba to jam with their Cuban counterparts, often producing collaborative recordings. This LP, organized and produced by multi-instrumentalist David Amram, is one such effort, and it’s a fine one.

Most prominently, it introduced two unknown and exciting Cuban jazz voices—trumpeter Arturo Sandoval and saxophonist Paquito D’Rivera–—to the American public. Soon after, while on tour, both Arturo and Paquito defected to the US, began touring and recording albums of their own, and became US citizens. Arturo Sandoval received the Medal of Freedom from former President Obama in 2013. Viva our cultural exchange programs!

What to make of The Case of the 3 Sided Dream in Audio Color (full title)—a double LP with side 4 blank, three-minute-long Kirk-spoken ramblings between tracks, two versions of three songs, and Kirk’s usual accomplished playing of two to three instruments at once? Sounds quirky, but it’s not.

With contributions from keyboardists Hilton Ruiz and Richard Tee, baritone saxophonist Pat Patrick (on holiday from Sun Ra), and drummer Steve Gadd, it’s downright groovy, possibly Kirk’s most broadly accessible album.

No question, here is a jewel produced by a seven-member jazz piano choir (Stanley Cowell, Nat Jones, Hugh Lawson, Webster Lewis, Harold Maybern, Danny Mixon, and Sonelius Smith).

Recorded live in concert, this two-LP album captured a seemingly unimaginable and otherworldly aural experience. Or as Phyl Garland of Ebony described it, “The torrent of sound springing from70 fingers is so powerful and majestic as to be unlike anything one has ever heard.” The sound produced, especially on the lengthier, driving all-hands-on-deck numbers, is orchestral. On other no less enjoyable tracks, there is at least a sense of familiarity—a theme statement followed by sequential solos by each choir member as in Monk’s “Straight No Chaser.” A stunning album.

Following on the heels of the big band revival of the late 1950s led by Duke Ellington, Count Basie and Maynard Ferguson, Herman launched the Fourth Herd in 1963, one of several bands he fronted over his musical career.

This latest edition featured aggressive soloists (Bill Chase, Sal Nistico, Phil Wilson) and current jazz standards “Watermelon Man” (Hancock), “Better Get It in Your Soul” (Mingus), and “Days of Wine and Roses” (Mancini). I saw this flat-out exciting aggregation at Basin Street East in New York City on my honeymoon.

A standout live performance by altoist John Handy and his unusual group: violin (Mike White), guitar (Jerry Hahn), bass (Don Thompson), and drums (Terry Clark).

It’s hard to say why this music is still so fresh and mesmerizing. It was novel, for sure, violin and alto, and guitar, but hey, this was the mid-’60s, novelty had been in vogue since the late ’50s. Sounded wonderfully alien to me, peculiar jazz harmonies some said, yet grounded in familiar jazz rhythms. Hard driving with group cohesiveness at its core, this was a memorable, one-of-a-kind performance.

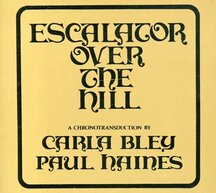

The Jazz Composers Orchestra Association (JCOA) was formed by Michael Mantler and Carla Bley to give avant-garde jazz musicians an opportunity to play large, extended compositions normally not economically or artistically viable.

The JCOA tapped the likes of trumpeter Don Cherry, trombonist Grachan Moncur III, violinist Leroy Jenkins, pianist Cecil Taylor, trombonist Roswell Rudd, and trumpeter Clifford Thorton to each create lengthy compositions to record. The best-known project, however, remains the massive opera Escalator over the Hill, produced by Michael Mantler, book by Paul Haines, music by Carla Bley.

Encapsulated in a three-LP box set with illustrated playbill, Escalator was performed by some 40 well-known American and European new wave musicians with contributions from pop stars Jack Bruce, Linda Ronstadt, and Viva. Although not designed for wide audience appeal, this monumental work stands as a defining artifact of that overly ambitious and optimistic decade, the 1960s.

These are but a tiny few of the exceptional treasures from my jazz LP collection. Nonetheless, I think you’ll agree with my conclusion from part 1: Over a 30-year period beginning in 1954, I was a fan with eclectic tastes, preferring a diverse mix of traditionalists (Powell, Green, Gillespie) and avant-garde musicians (Grachan Moncur III, Loft Jazz Artists, Carla Bley).

Thank you for accompanying me on my trip down memory lane.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed