Critic Dan Morgenstern covered Monterey’s 10th annual jazz festival for DownBeat, his first time doing so, and he came away quite pleased [1].

September 15

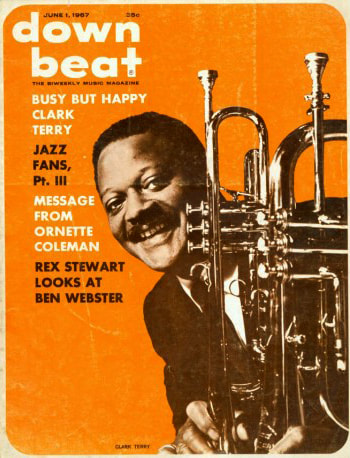

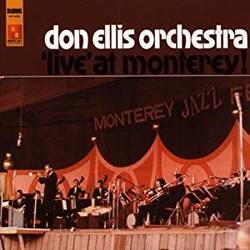

After a splashy afternoon opening, the showing of a commemorative film, the launching of gaily colored balloons and blinding light effects with an opening blast from the Don Ellis big band, the festival got down to business with the entertaining Dizzy Gillespie Quintet with James Moody (sax/flute), Mike Longo (piano), Russell George (electric bass), and Candy Finch (drums).

Diz and crew would back up other artists throughout the festival. Ubiquitous, irrepressible Diz joined the MJQ, Carmen McRae, and the Ellis organization onstage.

Saxophonist Illinois Jacquet, like Diz, appeared at Newport and, backed by festival mainstays John Lewis (piano), Ray Brown (bass), and Louis Bellson (drums), demonstrated that he was more than an extroverted stomper, playing ballads—even one on a bassoon!—but reverted to form, as at Newport, on his closer “Flyin’ Home.”

Next, the Don Ellis outfit offered a full set, highlighted by the rhythmically intricate New Horizons, the intriguing In a Turkish Bath, and the climactic Open Beauty. The band, Morgenstern admitted, “has a new palette of sound. The reed section (at one time featuring three soprano saxophones; at another, amplified flutes) is the most colorful, the trumpet section is the most brilliant. And the sound of the three basses bowing staccato together is something else.”

Overall, the band was much more impressive than it had been at Newport.

Newport had its vibe summit, and Monterey had its violin conclave with Europeans Svend Asmussen and Jean Luc Ponty and Americans Ray Nance and Stuff Smith—four distinct stylists that reminded everyone of the stringed instruments oft-overlooked but important role in jazz.

September 16

Morgenstern concluded that the blues afternoon was perhaps the greatest crowd pleaser of the entire festival. It began with the rousing gospel of the Clara Ward Singers and didn’t let up with blues singer/guitarists T-Bone Walker and B. B. King.

Interpolated in the midst of the bluesy afternoon, the Gary Burton Quartet with guitarist Larry Coryell received a well-deserved accolade from Morgenstern, who praised the empathy between players and noted that the ensemble was one of the most original and refreshing groups in contemporary jazz.

Early in the set, people began to dance, and soon they were snaking up and down the aisles while others stood on chairs digging and/or shaking, backed by shouts from others in the audience. That’s what it was all about—getting people to enjoy themselves.

Singer Mel Torme, appearing for only the third time at Monterey and backed by the Woody Herman Orchestra, offered a sparkling display of jazz singing. His set included a perfect Gershwin “Foggy Day,” a Porgy and Bess medley he also played on piano, a brilliant “Who Can I Turn To?,” a pyrotechnic “Bluesette,” during which the singer ate up the changes, and a fun-filled, scat-laced “Route 66,” which swung all the way. Morgenstern claimed he had never heard him better.

The Modern Jazz Quartet (MJQ to fans)—John Lewis (piano), Milt Jackson (vibes), Percy Heath (bass), and Connie Kay (drums)—opened their set with three numbers (including a superb “Pyramid”) before trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie came onstage during Jackson’s “Novano” and grabbed a piece of the action.

He remained for “Round Midnight” (both Diz and Jackson shone), and the “Bag’s Groove,” a triple treat for trumpet, vibes, and pianist Lewis. All in all, Morgenstern concluded, one of the musical highlights of the festival.

Closing things out for the evening were the Ambrosetti Quartet from Switzerland, including a gifted father-and-son team: Franco on trumpet, Flavio on alto. Both horn men proved excellent players with a good grasp of the idiom. And their set swung happily in a modern mainstream mold with avant-garde touches.

September 17

The day opened with the Ellis orchestra playing their second set, the music of Louie Bellson, who also sat in on drums. With Don Ellis conducting, the band tackled “Sketches,” a long, episodic number with moments of beauty, but the most moving Bellson piece was the memorial to Billy Strayhorn (who had died earlier in the year)—“unsentimental but full of feeling” was how Morgenstern described it.

For a climax, drummer Bellson featured himself, a set piece à la Buddy Rich, but with more attention to detail, if less volcanic power.

Guitarist Gabor Szabo’s group also drew a strong response from the crowd with “Spellbinder,” “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” and a piece with a long, unaccompanied bass solo, interesting ensemble counterpoint, and a rhythmically driving climax with tambourines a jangling.

Morgenstern reckoned that the group, while original, was not that radical. Elements of rock and raga entered into the picture, but they blended with a lot of jazz.

As it was at Newport, only one “New Thing” group was invited to Monterey—none other than a quartet fronted by the grand old man of “Free Jazz,” Ornette Coleman. His sidemen consisted of two bassists Charlie Haden and David Izenson and drummer Edward Blackwell.

Coleman’s most successful offering was his stunning saxophone during “Haight-Ashbury.” A trumpet piece was best on the ballad sections, less so on the up-tempo passages. It was graced by a fine, too-short Izenzon arco solo and expert use of mallets by Blackwell. Ornette’s turn on musette was a bit monotonous, however. “His new group promises much” was Morgenstern’s overall conclusion.

Next, yet another workout for the Ellis orchestra, this time playing the music of Yugoslav composer Miljenko Prohaska, who had had brought a lot of music and also conducted. Unfortunately, a good portion of the audience left during his set, and many missed the better parts of it.

Guest jazz soloists took part in most of the pieces—James Moody on alto and flute, Dizzy Gillespie once again, and drummer Louis Bellson. Morgenstern commented that the piece had to be one of the best ever written for drums and orchestra, and it inspired Bellson to a fantastic display of endurance, craftsmanship, and musicality.

Dizzy’s second set with his festival quintet began the evening with some monkey business, got the expected laughter, then landed a knockout with his horn on “Get That Money Blues,” followed by an old, pretty ballad “Accent on Youth.”

Next up, Diz’s old boss Earl “Fatha” Hines in a trio setting with Bill Pemberton (drums) and Oliver Jackson (bass) offered “Second Balcony Jump” and “Satin Doll.” Hines summoned reedman Budd Johnson to sing “Bernie’s Tune” and then play “It’s Magic” on soprano sax, switching to tenor to uncork a sizzling “Lester Leaps In.”

Backstopped by pianist Norman Simmons, drummer Candy Finch, and bassist Ray Brown, Carmen McRae etched “Midnight Sun,” gave “Lots of Love” new life, sang “Don’t Explain” in her own way, had a ball with “Satin Doll,” commanded attention with “For Once in My Life,” and broke it up with “Alfie.” It was, Morgenstern gushed, a masterly performance by a brilliant artist.

Bill Holman brought the festival to a close by conducting the Woody Herman orchestra in Holman’s Concerto for Herd. The opening section featured rich reed sounds piloted by Herman’s alto. The second movement brandished new textures of sound without resorting to freakishness.

The music was so moving that it lingered on through the opening of the final rousing movement that kept building without losing momentum. Morgenstern rhapsodized: this concert was the best music written for Herman since Summer Sequence (and of a higher caliber).

Time to go home.

Not everyone was pleased with 1967 MJF. Columnist Phillip Elwood argued that the festival had gone soft and conservative by presenting almost exclusively tried-and-true and popular performers—against the MJF charter that pledged to introduce important unknown artists and reacquaint the public with neglected jazz giants rather than playing it safe with a parade of name attractions [2].

Elwood cited several important artists that had never been invited to Monterey: Cecil Taylor, Roland Kirk, Archie Shepp, Don Friedman-Atiller Zoller. He contrasted this lineup with the 1967 MJF roster, which, for the most part, reads like a 78 rpm top pop-record list of 20 years before: Mel Torme, Dizzy Gillespie, Woody Herman, Earl Hines, and Illinois Jacquet.

Point well taken, Mr. Elwood.

- Dan Morgenstern, “Mellow Monterey,” DownBeat, November 16, 1967, 23–30.

- Phillip Elwood, “Playing It Safe?,” San Francisco Examiner-Chronicle, August 17, 1967.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed