The Modern Jazz Club

I likened the Modern Jazz Club in Cleveland to a hidden grotto where members of a breakaway religious sect came to worship their unrecognized gods, risking not life and limb so much as their social standing and reputations. There was a palpable excitement and danger to it all.

To talk jazz, life on the road, and women with these modern-day troubadours between sets was heady stuff for an outwardly reserved young man of 20 only recently discharged from the army. The exotic sounds heard nightly by the privileged few inside the Club—as it was known to aficionados—seemed all the more precious since it was beyond the hearing range of the ordinary public.

From the outside, the Club looked like a huge gray cinderblock that had fallen from on high but still managed to draw attention to itself by a single-entrance front door and one nearby recessed window with a neon sign that flickered a cursive Mod n Jazz Club.

The very sight of it brought on desolate thoughts and feelings of hovering loneliness. It was the only building left standing on Carnegie Avenue overlooking the industrial flats below for about a quarter-mile stretch between the arching Lorain-Carnegie bridge that connected the West Side to the once glorious, since faded downtown with its soot-encrusted banks and office buildings clustered around the landmark Terminal Tower.

The thousands of bus riders who passed the Club daily had to assume it was abandoned, awaiting the wrecking ball (forget the neon sign—that was there to ward off intruders). The fresh fish and fruit stall vendors at East Side Market on the other side of Carnegie Avenue probably took little notice.

The building was hard to see through the pollutant haze rising from the belching steel mills and manufacturing plants in the flats below. What vendor would risk life and limb to cross Carnegie among the streaking trucks and city buses to get to that dump anyway, assuming there was a reason to go there?

At least, that’s the way I remember it.

Inside—now, that was another story. The outer door opened to a closed vestibule quadruple the size of a phone booth, room enough for Tony the bouncer, a wall phone, and three patrons (two in winter when heavy coats and galoshes were worn). This was by design. The Club had a policy of not tolerating drunks, Tony made certain of that. In that close space, with his imposing size and Italianated demeanor, he collected the two-dollar cover charge (three dollars on weekends) asked for in the most threatening voice imaginable.

Tony knew how to ferret out potential troublemakers and lay down the law. “You like jazz?” he would ask. If the tipsy fellow answered, “Yeah, man, I’m hip,” or worse, “I dig Benny Goodman and Lionel Hampton, you know, the Vibraharp Champ.” Pretenders and swing fans need not apply.

Tony knew the guy had come to hear “Moonlight Serenade” and “Tuxedo Junction,” and would invariably become annoyed when the West Coast cats on the stand launched into an extended fugue with flute, oboe, and muted trombone. After all, this was the Modern Jazz Club.

In these instances, Tony would look the guy in the eye and growl, “Make a noise when the musicians play and I’ll mash your toes,” with a smile on his face, of course. If the guy nodded, Tony opened the door. If not, Tony shoved the two dollars in his hand and simply said, “Get out.” The crowds at the Club, according to the musicians, were the most respectful in the country.

But once the door to the club opened, you had to be impressed—that is, as soon as your eyes became accustomed to the prevailing darkness, especially on Monday nights when hardly anyone came. The sightline immediately ahead revealed a long, polished mahogany bar fronted by a row of perfectly aligned stools. In the middle of the bar sat an overly large and noisy cash register with a tendency to ring at the wrong times.

Many a dirty eye was cast in the direction of Shecky, the gruff, silver-haired bartender, who timed his commercial transactions during the set, never during the break, always during a slow ballad and never during a raucous, up-tempo jam. I was certain he hated the music. But being part owner, he could do whatever he wanted. Still, he was my bud, served me 6 percent beer right from the start, although at the time, it was illegal to do so for anyone under 21.

Behind the bar, a mirror fronted by shelves crammed with bottles of whiskey and bourbon reached to a rather low ceiling. Most bottles topped with a silvered pouring nozzle, ready for action. Christmas lights were strung along the shelves, and the entire bar area radiated a pervasive amber glow. A welcoming hearth indeed—shelter from the prevailing gloom that was Cleveland.

In a city of ten thousand neighborhood bars, one on every corner, it seemed, the Club bar would garner a four- or five-star rating, assuming someone would even care to rank it. The Cleveland bars were so ubiquitous, so taken for granted, it would be like ranking traffic signals, so no one bothered.

As you headed to the bar, you would need to step left to avoid the coat checkroom, the cigarette dispenser, and finally the jukebox, a genuine Wurlitzer, squat and thick, bubbling and glowing like a carnival carousel. Never ever, at least in my lifetime has there ever been such a well-stocked jukebox.

The classics, to be sure, some Louis Armstrong Hot Fives and Sevens, the 1940 big bands of Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Artie Shaw (thankfully, no Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, or Glenn Miller, the stuff you could hear anywhere). Plenty of sides from the bebop pioneers Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. Sarah Vaughn. Some Billy Holiday, newcomer Nina Simone.

But important to me was the modern stuff: cuts from early Miles Davis (Walkin’) and Thelonius Monk on the Prestige and Blue Note labels, Miles’s first Columbia LP (Round Midnight), the MJQ on Atlantic, Oscar Peterson and Stan Getz on Verve, Kai and JJ on Bethlehem, the West Coast cats—Chet Baker, Jimmy Giuffre, Art Pepper, Shelley Manne—on independent labels Contemporary and Pacific Jazz.

And Duke’s new band rocking Dimuendo and Crescendo in Blue at Newport on Columbia and the Count’s latest aggregation swinging “Corner Pocket” and “Shiny Stockings” on Verve.

It was the new sounds, less pleasant to the ear at first, but more familiar with repeated listening, that ultimately gave me the most pleasure.

I would arrive at the Club an hour before the first set to hear the latest offerings, always hoping someone would be there to feed the hungry Wurlitzer. Jimmy Smith, the first to play bop organ, was hard to take at first, he sounded too much like an underwater popcorn maker (if there was such a thing). And Cannonball Adderley’s swooping alto sound, so un-boplike, bothered me too. Don’t know why.

And what in the world was that Pithecampus Erectus thing by Charles Mingus? Total cacophonic chaos? Not really—it was the first aural sign of the Free Jazz movement that, in retrospect, was bursting on the scene in 1958, although many of us ardent jazz fans were clueless at the time. That jukebox was as responsible for my jazz education as DownBeat magazine, the record shops around town, and Tom Brown’s nightly radio jazz show on WHK.

That glowing Wurlitzer was to the Club as a coal-fired potbellied stove was to old-timers at a rural general store, or a stick fire to prehistoric man—a central source of warmth for all to gather about and swap tales. The musicians came to hear the newest sounds and pick up on the latest buzz.

With their busy schedules, on the road, hopping from town to town every week, and their need to focus on their own music, the musicians had less time than I did to follow the new thing—a fact that always bothered me. I wanted to learn from them, not the other way around.

I asked them, “Who do you like best on alto, Art Pepper or Lee Konitz, and are there some other guys I should know about?” And, “On that platter that you did with Terry Gibbs on Emarcy, who picked the tunes? Did you like the way Gibbs played? Is he better than Milt Jackson?”

Their answers always disappointed: “Never played with Konitz, don’t know,” and “Is that Gibbs album out? I haven’t heard it. Gibbs, he’s cool, so’s Jackson. MJQ, right?” How the hell was I supposed to learn about jazz if the musicians knew less than I did? After all, they were jazz musicians and they should know this stuff. I couldn’t even read music for Chrissakes, couldn’t play chopsticks if my life depended on it.

You may be wondering why these skilled musicians would ask me anything. It had to do with an assumption: no kid in his right mind (white kid, especially) would come to a jazz club (without a chick) just to listen to the music. I just had to be a musician, picking up technique, that sort of thing. Sure, fans existed, but in New York City, not polka-belt Cleveland, and certainly not a twenty-year-old like me. Jazz fans were older. Teens, well, they dug the Hit Parade, Elvis, rock and roll, American Bandstand, maybe R&B, Dinah Washington if they were hip, but not jazz.

Worse still, some of the bandleaders would saunter up to the box where I hung out, listen to a few cuts and start grilling me. “Hey, you seen this Grant Green in here?”

I’d say, “Well, no, he plays Detroit mostly—that’s what DownBeat says.”

“What else they say? I may be needing a new guitar soon.”

“They think he’s the next Wes Montgomery, but I heard him on that album with Lou Donaldson, and he sounds like Kenny Burrell, maybe funkier.”

“Hmm, funky. Whatcha mean?”

“He plays harder,” I’d say. “The notes are harder, more distinct, what you say, articulate. He digs blues and gospel, plays down and dirty.”

“Think he’ll fit in my band.”

“If you could get him to tone it down, play it smooth, a duller tone maybe, chording like Barney Kessel.”

“Let me tell you who I like, kid. Oscar’s man Herbie Ellis. You come here often, right? Ask him if he’d play with me.”

What did these guys think I was? A music critic? An agent? It was almost more than I could bear.

I got a kick every time the George Shearing Quintet hit the Club. Between sets, blind George plopped down next to the box, had his valet drop quarters and punch nothing but MJQ tunes. Shearing would hug the Wurlitizer like it was a red-hot mama, moan, and rock back and forth—it was embarrassing to watch, actually—occasionally shrieking out, “Percy. Percy. Percy. Listen to that bass. I’ve got to get old Percy Heath in my band. We could swing up a storm. Walk it, Per-ceee, walk it!”

I felt like a Peeping Tom, nose pressed against a bedroom windowpane. Three times I witnessed Shearing’s orgasmic rapture and convinced me for life that sightless people do have superior hearing ability, capable of plumbing unfathomable aural depths.

The rest of the Club? Quite ordinary, really. From the bar forward, a shoe box about 40 feet across stretching some 60 feet to the raised, wooden-plank bandstand that supported a piano, three microphones, and the musicians and their instruments, back dropped by a black curtain. In front of the bandstand, small round tables the size of birdbaths crammed together with two or three chairs circled around them.

The Club sat 100 some people, I guess, although on matinee Sundays, I swear there were 500 people in the place. Low ceiling, brick walls, no posters, speakers hung by the stage, over the jukebox, by the door. Didn’t need them really. That was it—your standard New York City jazz club transported to Cleveland.

But it was the music, oh God, the music.

In my unforgiving youthful state, how could I have known that almost half a century later, many of the musicians that stood on that sagging stage would reach legendary stature?

Those 1957–1959 years would be one of those singularity periods in jazz, a period now recognized as one the most fertile in jazz history, like 1922–1925, when Louis Armstrong and the Chicagoans first burst on the scene, or 1937–1939, when New York City blossomed full flower led by Duke, Goodman, and the Commodore Records crowd, or 1943–1946, when the bebop revolution of Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, and Charles Parker sprang from Minton’s Playhouse.

I saw the jazz giants of 1958 up close, watched their every move, talked to them. How could I have known they’d become legends?

At the time, they were my superheros, my nighttime DownBeat reading come to life. I had most of their records (skipped lunch to buy them). Records I didn’t have, I listened to in record shop booths for hours to the chagrin of storeowners—that’s why I had so many LPs. I had to buy them to gain afternoon access to the booth. But most important, it was my music.

I discovered jazz. I had to—who else but me knew about it? I didn’t know a kid my age in the whole of Cleveland who knew about it. I never saw any in the record shops either. Okay, I met two guys in the army who knew: a black guy from Detroit who turned me on to the Blue Note/Prestige sound and a surfer dude from California who knew all about the West Coast jazz scene.

Other than that, I was on my own. My mother was clueless, convinced the music was some Bolshevik anarchy crap that would turn me to dope and the Communist Party.

Early on, when kids my age listened to Teresa Brewer, Nat King Cole, Elvis, Pat Boone, as I did too, my ear still went to the occasional pop radio offerings of Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughn and the Four Freshman, the trombone breaks in the their songs tricking my ears. From the radio, to the record shops and the back-of-the-store listening booths to spend an afternoon, listening to one platter after another until the shop owner kicked me out. Nobody my age in Cleveland knew about jazz. I was the only one who knew.

At least that’s the way I remember it.

I saw and heard a virtual who’s who of the jazz world. Fiercesome pianist Oscar Peterson just had to be the hardest working man in show business (apologies, James Brown), especially on up-tempo numbers, sweat dripping off his face, his fingers flying lickety-split over the keyboard, accompanied by audible growls as guitarist Herb Ellis and bassist Ray Brown did their damndest to keep the pace.

It was quite a contrast to the pastoral jazz offered up by clarinetist Jimmy Giuffre’s trio with valve trombonist Bob Brookmeyer and guitarist Jim Hall that chased conventioneers out of the Club.

I can’t remember them all now. The hard bop quintets of Horace Silver and Art Blakey would come in for a week (not a day as now), followed by groups from the West Coast, mostly led by the sidemen from my back-store booth listening sessions: Shelley Manne, Shorty Rogers, Bob Cooper.

One outfit, a Cleveland favorite called themselves the Australian Jazz Quintet, featured a hard-charging tenor and alto duo with rhythm that totally blew everyone away when they switched to oboe and flute. Then Dizzy Gillespie showed up for a Sunday matinee with his State Department overseas-touring band to play before a packed house.

The stage couldn’t hold them all. Patrons had to be pushed back to make room for the sax section in front of the riser. I’ll never forget the closing number that lasted a half hour, seemed like, with Diz and the band shouting, “Take Me Back to Georgia,” over that body-shaking Manteca rhythm, capping it off with a hankie-waving “bye bye” finale. It ended with such thundering applause that the whiskey bottles jiggled on the shelves behind the bar.

But the most memorable evening occurred on a Monday night in April 1958 when Miles Davis brought his new sextet to the Club.

Miles and Me

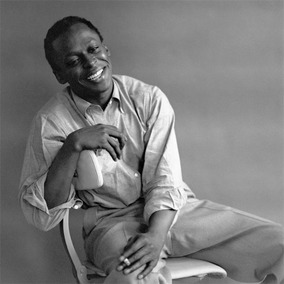

Miles Davis, 1955. © Tom Palumbo.

Miles Davis, 1955. © Tom Palumbo. Miles’s new sextet consisted of three players from his first great quintet—star tenor sax player John Coltrane, bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Philly Joe Jones—and two newcomers: alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley and pianist Bill Evans. Seven months later, this group (with Billy Cobb on drums instead of Philly Joe) would record the classic Kind of Blue, now the best-selling jazz album of all time.

A surprisingly small crowd for a Monday night eagerly awaited the first set, which was delayed by some fifteen minutes. Minus Miles and Philly Joe, the musicians finally assembled on-stage and talked among themselves for a spell before taking their positions.

Cannonball stepped up to the microphone and announced, “Welcome to the Miles Davis Drumless Sextet,” further explaining that drummer Jones, whose plane landed at the airport that afternoon, but his drum kit did not, was busily scouring the city for a set of drums, and he’d soon arrive at the Club with his instrument.

Cannon announced the first tune, Charlie Parker’s “Ah-Leu-Cha” off the Round Midnight LP, and then set the rhythm by snapping his fingers as Miles, trumpet in hand, sauntered on stage to join the drumless quintet in a rousing version of the bebop classic. From my bar stool near the jukebox, absent the drums in that half-empty Monday night space, I clearly felt the pulse and heard each instrumental voice perfectly, something you would never ever hear on a record.

Miles and Coltrane sounded different than they did on their recent Round Midnight and Relaxin’ LPs. Miles’s trumpet voice was stronger, brighter, and Trane’s improvisational turn was lengthier and more multi-noted. Six months later, critic Ira Gitler would characterize Coltrane’s emerging style as “sheets of sound” in the liner notes to Soultrane. The epithet would stick, and I couldn’t disagree based on what I heard that night.

DownBeat articles chastised Miles for his habit of turning his back on the audience. At the Club, when others soloed, the ostensibly brooding trumpeter walked off the stage, to the side, behind a flimsy black curtain. To me this behavior was not a sign of disrespect for the audience or the players. Quite the opposite, it was his way of focusing attention onto his fellow band mates during their solos. At least that’s the way I saw it.

Newcomers Adderley and Evans sounded a lot better to me in person than they did in the listening booth. My ambiguous view of both musicians changed significantly during the first number. Cannon could hold his own with any extant alto sax player—Lou Donaldson, Jackie McLean, Sonny Stitt—with a distinctive alto voice all his own.

I was disappointed when Miles dropped my favorite Red Garland—the block chord master of the slow blues—for Bill Evans, who didn’t sound like anyone else. He played block chords, too, but soft, cottony ones, not definitive and ringing the way Garland did. Against expectation the Evans piano meshed well with the band.

The rest of the set was a marvel to behold. Cannon, as gracious emcee, set the tempo for each number with adroit finger snaps that in some cases lasted for the entire tune. Miles remained on stage for the ensemble and his solo, but otherwise stayed in his special place behind the black curtain.

The tunes, as I remember them now, made up the standard Davis nightclub repertoire—ballads, blues, bebop classics—that would eventually show up on the Prestige LP series Relaxin’, Workin’, Steamin’ and Cookin’. The set was longer than usual, with everyone stretching out, Trane taking full advantage of the situation.

No doubt the band was covering for Philly Joe, who, it was later said, went frantically knocking on every high school band director’s door looking for a drum kit. Cannonball closed the first set by assuring the house the next set would not be drumless.

It was break time.

All the musicians left the stage save for Bill Evans, who never left his piano bench. Hunched over the keyboard, he played ever so lightly so only he could hear his impressionistic excursions. Cannonball joined some fans at a table and engaged them in an animated discussion. Coltrane dragged a chair to the right of the riser, pulled out a magazine, sat down, and began reading.

I left my bar stool and edged closer to where the tenor titan sat, hoping he might be reading DownBeat, a chance to start up a conversation. When I got closer to his corner, I found him chewing gum and reading a comic book—not exactly what I had hoped to find. I returned to my bar stool.

Paul Chambers and Miles had left the scene. But then out of nowhere, the brooding trumpeter reappeared on the stage, staring straight ahead. He stepped off the riser and threaded his way through the patrons at their tables and headed straight to the bar.

He stopped at the first customer and leaned in, then moved around to the next bar stool customer, stepped back, and moved to the next. There, same thing. Oh, my God, Miles was coming my way. I twirled around on my seat, facing away from the bar, and made ready to greet the hamlet of jazz.

Miles stepped in front of me and in that raspy whisper voice of his, he asked, “You play drums, muthafucka?”

I froze in place while my cortex went into overdrive. Miles thinks I’m a drummer for God’s sake. Just like all those other musicians who came to the Club, he thought I was a player. No, I’m just a fan. But what do I say to Miles. Do I just say no? This is MILES DAVIS. I’ve got to say the right thing, but what?

All the while his eyes are locked on mine. He doesn’t even blink. And he doesn’t say anything. I see his head wagging back and forth ever so slightly. What’s he thinking? Why are all these white boys so stupid? As I open my mouth to speak, he moved on to the next guy at the bar, and I heard him say, “You play drums, muthafucka?”

Then it dawned on me—he was looking for drums just like Philly Joe. Damn!

Just as Miles reached the end of the bar, in rushed the prodigal drummer followed by Tony, both carrying the various pieces of a drum set: snare, bass drum, cymbals, and high hat. Mission accomplished.

I swiveled back on my bar stool, asked the bar keep for another beer (even though I couldn’t afford it), hung my head, and lamented how I had blown my big opportunity. I could have asked him why Red Garland was no longer with the band and about that new album Miles Ahead everybody was talking about—a chance of a lifetime gone up in smoke.

The second set began like the first with Cannonball at the mic introducing the Miles Davis Sextet with Philly Joe Jones on the drums. The music began. I don’t know where Philly found those drums, but the ride cymbal could have been a garbage can lid, the bangy, splashy sound ricocheting off the walls, drowning out the rest of the band.

I downed my beer, slid off my seat, and headed for the door into the Cleveland night air and the nearest bus stop. Oh well, the night wasn’t a total loss. The music was great, and I could tell people I once met Miles Davis, and he asked me if I could play drums.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed