All anniversary years are special, but 2015 is EXTRA special. It’s the 100th anniversary of the birth of three iconic jazz figures: Billy Strayhorn, Billie Holiday, and Frank Sinatra.

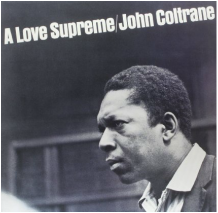

For jazz fans, 2015 will be a Yogi (“déjà vu all over again”) year for A Love Supreme. The music public could turn on to Coltrane’s multi-movement symphony as well, triggered by Andrew Grant Jackson’s new book 1965: The Most Revolutionary Year in Music (St. Martin’s Press, 2015). The book devotes three pages to the album (nothing jazz fans don’t already know) and includes the title in the psychedelic swirl of iconic names on the cover next to MoTown, below Rubber Soul, and above The Wailers, Folk Rock, and The Beach Boys. Sales of the album will definitely uptick from all the publicity.

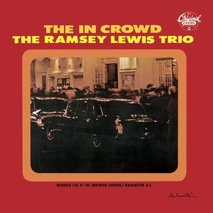

Think of it, a jazz-piano-trio single that vied with notable pop and rock hits for chart space: “Satisfaction,” “Tears of a Clown,” “Norwegian Wood,” “I Got You Babe,” “Do You Believe in Magic,“ “Gloria,” “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag,” “Uptight,” “Ticket to Ride,” and “Yesterday,” among others. Interestingly, there is no mention of “The In Crowd” in Andrew Grant Jackson’s 1965 book. For the full story, check out Michael West’s recent article in the Washington Post. (1) And to hear it in glorious wraparound Dolby sound, go to your local multiplex to see Woody Allen’s newest entry in the Oscar Sweepstakes Irrational Man. It is the soundtrack, played almost nonstop from beginning to end.

And let’s not forget, 1965 saw the founding of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) in Chicago by pianist and composer Muhal Richard Abrams. Among its early members would be reedmen Joseph Jarman, Roscoe Mitchell and Anthony Braxton, trumpeters Lester Bowie and Leo Smith, drummer Steve McCall, and the violinist Leroy Jenkins. Roscoe Mitchell would be the first to document this new music on record the following year.

As for the 1965 Newport Jazz Festival, Whitney Balliett of the New Yorker summed it up as “bland, banal, occasionally original, never exciting and . . . unintentionally funny. This comedy made the general mediocrity of the [four-day] weekend bearable.”(2) Well, it wasn’t all that bad. The MJQ presented an excellent set, as Balliett acknowledged, and many enjoyed an afternoon of drum legends Jo Jones, Buddy Rich, Roy Haynes, Louis Bellson, Art Blakey, and Elvin Jones. Top Balliett honors went to Jones for his ability to manipulate two or three rhythms at once.

To his credit, producer Wein allocated significant time to the “New Thing” musicians (Carla Bley, Paul Bley, Archie Shepp, and Cecil Taylor) that wasn’t well-attended, well-received, or well-introduced. MC Leonard Feather warned the audience, “Listening to this new music is not easy, but involves real effort, not mere receptiveness.”(3) Dizzy Gillespie was his usual ubiquitous self, sitting in with several groups and subbing for an ailing Miles Davis. Frank Sinatra provided Balliett’s “comedy” by his over-the-top arrival and departure that bookended his appearance with the Count Basie Orchestra, all carried out with commando precision.

At exactly 19:25, Sinatra and his entourage descended from the heavens in two helicopters with a roar, setting down behind the bandstand. At 21:00, Sinatra paraded onstage to join the Basie aggregation with his own drummer, trumpeter (Harry “Sweets” Edison), arrangements, conductor (Quincy Jones), and soundmen (who tinkered with the sound system to its detriment.) Allotted only five minutes for picture taking, photographers scurried about shooting fast and furious.

Frank then launched into a 20-song set that began with “Get Me to the Church on Time,” and included “Where or When,” “Street of Dreams,” and a boorish mid-set monologue, not unlike that heard on the Sinatra at the Sands LP recorded some seven months later. Set over, the capacity crowd of 15,000 embraced the singing legend with lengthy warm applause. With Basie’s “One O’Clock Jump” in the background, another roar, a slowly ascending helicopter blinked its red and green lights goodbye. It was a memorable evening. Wein packed the house. Ol’ Blue Eyes sounded great to some, not so to others, but it didn’t matter. This night, stagecraft trumped performance.

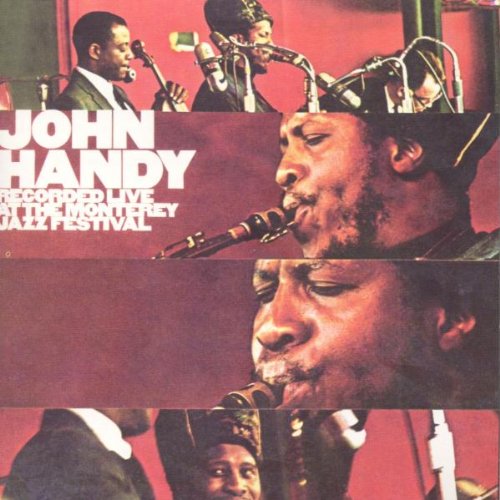

At the Monterey Jazz Festival, the standout performance was by altoist John Handy and his then unusual group, violin (Mike White), guitar (Jerry Hahn), bass (Don Thompson), and drums (Terry Clark). They played two long, captivating instrumental pieces that to this day remain as exciting as they were that September night. It’s hard to say why this music is still so fresh and mesmerizing. It was novel, for sure, violin and alto, and guitar, but, hey, this was the mid-sixties—novelty had been in vogue since the late fifties. That couldn’t have been it.

| It sounded alien to me, wonderfully so, as if touched by several unidentifiable musical influences. Peculiar jazz harmonies, some said, yet grounded in familiar jazz rhythms. Hard driving with group cohesiveness at its core, this was a memorable one-of-a-kind performance. Columbia recorded the music of Handy, White, Hahn, Thompson, and Clarke that night, releasing the John Handy Recorded Live at the Monterey Jazz Festival album in 1966. Check out part 2 of this post next week for a list of other worthy jazz albums of 1965. |

- Michael West, “In the Year Jazz Went Avant-Garde, Ramsey Lewis Went Pop with a Bang,” The Washington Post, April 3, 2015.

- Whitney Balliett, Collected Works: A Journal of Jazz 1954–2001 (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2002), 242–43.

- Burt Goldblatt, Newport Jazz Festival: The Illustrated History (New York: The Dial Press, 1977), 122.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed