The 100th anniversary birthday calendar for this year is chock a block with 18 total centenarians, oldest to youngest as follows:

Money Johnson, Marian McPartland, Sir Charles Thompson, Howard McGee, Sam Donahue, Peanuts Hucko, Hank Jones, Rusty Dedrick, Eddie Jefferson, Arnett Cobb, Ike Quebec, Jimmy Rowles, Gerald Wilson, Tommy Potter, Jimmy Blanton, Bobby Troup, Joe Williams, and Jimmy Jones. (1)

I will single out four, each with a Duke Ellington connection, three of whom performed at the White House tribute to Duke Ellington on his 70th birthday on April 29, 1969.

Jimmy Blanton

In that brief time, according to Whitney Balliett,

Ellington starred Blanton and his instrument in concerti like “Jack the Bear” and “Bojangles” . . . as well as the highly unconventional duets that he recorded with Blanton—“Pitter Panther Patter,” “Mr. J.B. Blues” . . . his big tone and easy, generous melodic lines mov[ing] like rivers through every record they did together . . . His phrasing was spare and his silences were as important as his notes. He adopted a hornlike approach to his instrument—that is, he no longer just “walked” four beats to the bar but also played little melodies . . . Blanton’s accompanying was forceful; he pushed the band and its soloists by playing a fraction ahead of the beat . . . which lifted the band and made it swing. (2)

Marian McPartland

One of the first reviews she received as a jazz pianist at the Hickory House was by Leonard Feather in DownBeat magazine: “Marian McPartland has three strikes against her, she’s English, white, and a woman.” (3) Ten years hence, by the time her trio’s weekly stint at the Hickory was over, Marian had gained a measure of respect for her talents.

Her career for the next 10 or so years or so continued apace, performing at concerts and clubs, traveling extensively, and making one or two records every year.

Marian is probably best known for her Piano Jazz radio show that aired on NPR starting in 1978, where she interviewed and performed with hundreds of jazz (and some pop) singers, pianists, and other instrumentalists, continuously for 23 years. It won the coveted Peabody Award in 1984, the ASCAP–Deems Taylor Award in 1991, the New York Festivals Gold World Medal in 1988, and the Gracie Allan Award in 2001, presented by the Foundation of American Women in Radio and Television.

McPartland was named a Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), received a Lifetime Achievement Award from DownBeat magazine, and a Mary Lou Williams Women in Jazz Award. (4)

Not too shabby for a white English woman, eh, Mr. Leonard Feather?

As a lifelong admirer and friend of Duke Ellington, Marian was a shoo-in to be invited to perform at the maestro’s White House tribute on April 29, 1969. The Nixon administration went out of their way to make sure she did. They provided a limousine to shuttle her between the White House and her gig at nearby Blues Alley in Georgetown, managing to get her to the East Room in time for the late night jam session after the all-star band concert.

Duke greeted his Hickory House friend upon her arrival, and, fearing Willie “the Lion” Smith would monopolize the keyboard all night long, Duke urged Marian to take her turn at the grand piano. Once she was on the riser, the Lion said to her, “I suppose you want to play.”

“Yeah, I’d like to,” Marian responded, moving in a little.

“Okay,” Willie said as he walked off in a sulk. Ellington stood nearby chuckling to himself.

After a decent interval at the keys, McPartland zipped back to Blues Alley, where she greeted her guests with, “Sorry I’m late. I’m also doubling at the White House.” (5)

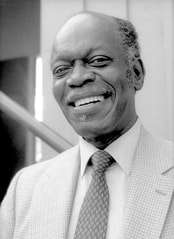

Hank Jones

From there, he became a Jazz at the Philharmonic mainstay (1940s), an accompanist for singers like Ella Fitzgerald (1950s), a CBS staff musician in New York City (1960s–70s), and the pianist on a thousand and one record dates. By then, his style had coalesced

Unlike most modern pianists, Jones constantly uses his left hand, issuing a carpet of tenths, little offbeat clusters, and occasional patches of stride. Jones’ solos judge, and they rest far above the florid, Gothic roil that many jazz pianist have fallen into. (6)

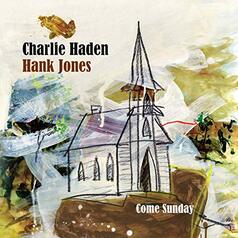

From the 1970s on, although Jones freelanced as before, he became widely regarded as the dean of jazz pianists through his recordings in the trio format—for example, Great Jazz Trio with bassist Ron Carter and drummer Tony Williams—and his duos with pianists Tommy Flanagan and John Lewis, bassist Charlie Haden, and guitarist Bill Frisell.

His rise in stature is evidenced, in part, by his NEA Jazz Master Award in 1989, his 19th-place finish in Gene Rizzo’s book The Fifty Greatest Jazz Piano Players of All Time (Hal Leonard, 2005), and his career-topping National Medal of Arts award bestowed by President George H. W. Bush in 2008. (7)

Along with guitarist Jim Hall, bassist Milt Hinton, and drummer Louis Bellson, Hank was a member of the all-star rhythm section that backed the all-star front line at Duke Ellington’s 70th-birthday celebration at the White House: trombonists Urbie Green (“I Got It Bad and That Ain’t Good) and J. J. Johnson (“Satin Doll”), altoist Paul Desmond (“Chelsea Bridge”), baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan (“Sophisticated Lady”), trumpeters Bill Berry and Clarke Terry (“Just Squeeze Me”), and the whole band on a raft of Ellington tunes.

No solos for Hank. Nonetheless, the pianist chorded the patented opening vamp Duke had crafted many years before on “Satin Doll,” and the East Room crowd reacted immediately—they knew what was coming—and trombonist Johnson delivered the familiar melody. (8)

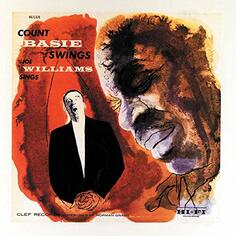

Joe Williams

Starting in the 1960s, Williams was a vocal soloist fronting various piano trios. He continued to expand his range, becoming a superior crooner and exhibiting a real depth of feeling on ballads. Recognition of this growth came in 1974 when Joe won DownBeat’s Critics Poll as best male vocalist—winning nearly every year thereafter for more than a decade. His stature as a polished and complete singer came in 1993 when he received the NEA Jazz Master Award. (9)

At the Ellington White House tribute, Joe sang three songs backed by the all-star band, starting with “Come Sunday,” which Gary Giddins has rightly crowned the Duke’s supreme contribution to the American hymnal. The spiritual theme was first introduced in 1943 at Carnegie Hall in Black, Brown, and Beige, Ellington’s first voyage into extended composition.

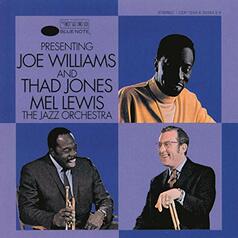

Williams loved singing Ellington songs and included at least one in nearly every performance. In his repertoire for some time, he sang “Sunday” at an earlier Ellington tribute in the summer of 1963 in New York City and again on record in 1966: Presenting Joe Williams: Tad Jones/Mel Lewis (Blue Note).

Mahalia Jackson’s rendering of this lovely hymn is unsurpassed. But on the male side of the ledger, no one has come close to matching the depth and poignancy that Williams has lent to the song. One of the critics in attendance the night of the tribute, Leonard Feather, characterized Joe’s version as “deeply moving.” Critic Morgenstern concluded, “Williams [is] singing as movingly as I’ve ever heard him.”

William’s brought the same amount of conviction and richness to “Heritage,” also known as “My Mother, My Father” as he did to “Come Sunday.” He sang slowly and thoughtfully, with the feel of an elegy. According to Doug Ramsey, there wasn’t a dry eye in the East Room when he finished.

A swinger from the satirical musical of 1941 of the same name, “Jump for Joy” closed out the All-Star band concert in truly joyous fashion. Joe’s caramel baritone perfectly enveloped the song’s gospel ardor and secular esprit. He had previously recorded “Jump” in 1963, and must have sung the song a hundred times after that 1963 studio date.

Whether it was this past familiarity with the tune, or Joe’s and the band’s sensing the concert finish line, Joe was out front but still solidly “in the pocket” for an all-out swinging climax to the concert. (10)

- Jazz Birthday Calendar, 1918.

- Whitney Balliett, Collected Works: A Journal of Jazz 1954–2001 (New York, St. Martin’s Griffin, 2002), 478–79.

- Marian McPartland, Marian McPartland’s Jazz World: All in Good Time (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2003), 1.

- Ibid., 166.

- Edward Allan Faine, Ellington at the White House, 1969 (Takoma Park, MD: IM Press, 2013), 138.

- Balliett, Collected Works, 837.

- Faine, Ellington, 60.

- Ibid., 93–133.

- Ibid., 66–67.

- Ibid., 126–30.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed