For his first opening act, he booked the inimitable Miles Davis. Kenny shares the story in his award-winning memoir, Off My Rocker*:

MILES IN THE RAIN

At the onset of 1985, I sat in the catbird seat, with the money and authority to book a 45-show summer concert series. There were a couple of problems, though. One, I didn’t know what I was doing. Two, Jerry Mack, the ousted promoter of record at Humphrey’s, was coming after us with a vengeance. He immediately went down the street to the far end of Shelter Island and started a competing series at the Kona Kai Hotel.

My first confirmation after becoming “captain of the ship” was Chuck Mangione, an artist whose music I equated with cotton candy, primarily fluff with no substance. One booking and I had already compromised my artistic values.

I dished out offers to any agent who would pay attention to me. That was a short list.

I pressed [Peter] Sheils [of the William Morris Agency] for days, trying to convince him to bring David Sanborn back to Humphrey’s. “I can’t, but stay by your phone.”

Famous last words that I would hear hundreds of times during my tenure as a concert producer. But Sheils came through the next morning.

“Are you sitting down?” he asked with an air of mystery in his voice that suggested that the original Mott the Hoople might be reuniting to tour.

“Go ahead,” I replied blankly, expecting an overpriced Stanley Turrentine confirmation at best.

“Okay. June 2 and 3, two nights of Earl Klugh. Confirmed. July 5, John Klemmer. Confirmed. July 20, Larry Carlton. Confirmed. And on April 21, your opening night will be . . . Miles Davis. Confirmed.”

I felt like a Major League Baseball GM who had just pulled off a spectacular four-for-one trade. All these artists added instant credibility to our series, but Miles Davis was the one I did backflips over.

Davis’s career was showing signs of revitalization in the early ’80s after he had disappeared into a cocaine haze from 1975 to 1980. The Man with the Horn, his 1981 comeback LP, had garnered positive reviews and reasonably good sales numbers, although his performances were erratic: brilliant one night, unfocused and plodding the next.

I didn’t know which Miles Davis would show up, but I did know that April was the tail end of the rainy season in San Diego and the forecast for April 21, which turned out to be accurate, was for sporadic rain accompanied by monsoonal winds.

I was neurotic enough about presenting my first concert without having the added distraction of intermittent rain throughout the evening. What if we had to cancel the show? Did we still have to pay the band? Of course we did, but maybe an understanding artist would give us some money back and share the loss with us. My naïveté was still in full flower.

During my first two years as a promoter, a consultant named John Harrington, a respected talent buyer for the Hollywood Palace, taught me the ropes and advised on the booking. He came down for the Miles Davis concerts and watched me with amusement as I paced back and forth in our dressing-room office, tensing up every time it began to drizzle. Harrington had seen it all during his career, but he’d never produced an outdoor event.

“Relax, Kenny, it’s a no-brainer,” he said. “The show goes on, the band plays, the show ends, everyone goes home, and you wake up tomorrow and do it again.”

With that pearl of wisdom, he whipped out a joint, lit it up, and insisted I partake.

“I don’t know, John. I still have to settle the show,” I said before taking the first of a half-dozen hits.

When the tour manager came by to get paid before the seven o’clock show, I was feeling no pain. I handed him the balance of the guarantee (Miles got paid $17,500 that night—supposedly a bargain) and went to the side of the stage to watch the performance. In later years, I’d sit in my designated ninth-row center aisle seat, but on this night, I didn’t want to be confronted by any audience members who might blame me for the weather.

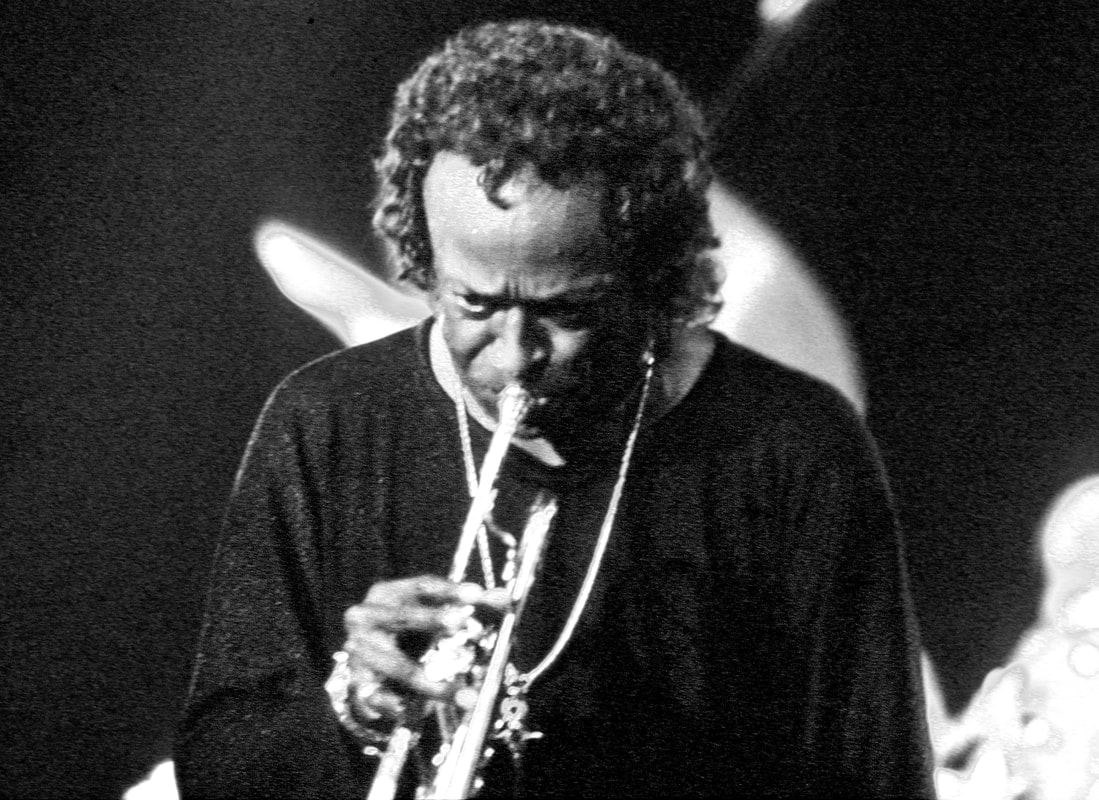

The early show started on time in a steady rain. By the second song, a little-known piece of funk-fusion called “Maze,” the sky responded with some up-tempo activity of its own, drenching the performers and the audience. Amazingly, the musicians played through it with smiles on their faces, including the trumpet-wielding front man.

Davis, dressed in black from head to toe, including a Gaucho hat, sunglasses, and gloves, never faced the crowd and didn’t say a word the entire night. But the performances were riveting enough to keep the fans (1,339 paid for two shows) mesmerized throughout their own mud-encrusted Woodstock by the Bay.

Even though Davis’s repertoire consisted of all recent material (no Birth of the Cool, Kind of Blue, or Bitches Brew that night), the audience was clearly excited by his playing as well as by his cherry-picked band of young lions that featured guitarist John Scofield, saxophonist Bob Berg, and future Rolling Stones bassist Darryl Jones.

In George Varga’s glowing concert review in the San Diego Union the next morning, he wrote, “If last night’s weather might have been better suited for a Jacques Cousteau television show about coastal storms, no one bothered to tell Davis. The mercurial trumpeter turned in a fiery performance that burned strongly from start to finish.”

When the second show came to a close, shortly before the 10:30 curfew, I wrestled with whether I should knock on Miles’s door to thank him for getting me through my “debut performance.” Even though he had a racially mixed sextet, he was notorious for his distrust of the white music biz establishment, especially concert promoters.

As I played head games with myself, his dressing-room door opened and I stood face-to-face with Miles Davis, who was heading to the green room for some post-gig food and beverage.

More than slightly tongue-tied, I extended my hand and thanked him, identifying myself as the promoter. I’ll never forget his handshake: a backhand, contorted twist of the wrist latching onto the tips of my thumb and first two fingers.

“How did you do?” he asked with his characteristic rasp.

“It really doesn’t matter,” I said, startled that a performer of his magnitude would be curious about the promoter’s financial outcome. “This was the first concert of my career, and no matter what happens from here on in, I’ll always be able to say that I presented Miles Davis in concert. You have no idea what that means to me.”

“Yeah, yeah. But how did you do?”

“We, uh, lost some money,” I said, “but I don’t care. Miles Davis just played at Humphrey’s and—”

He grabbed my wrist and looked me straight in the eye. “Next time,” he said, “you gotsta charge more.”

It reminded me of the simplicity of David Carradine in Kung Fu. If I had charged more, the bottom line would have been higher and we might have broken even. He nodded and proceeded down the path to dinner enlightenment.

In 1986, we presented Miles Davis again. Adhering to Miles’s strategy, I raised the ticket price from $16.50 to $18.50. Attendance dropped by 200 and we lost $2,500.

*Excerpted with permission from Off My Rocker: One Man's Tasty, Twisted, Star-Studded Quest for Everlasting Music, published by Sandra Jonas Publishing, 2013.

|

KENNY WEISSBERG has worn nearly every hat in the music industry. He produced and hosted radio shows for eight stations from 1971 to 2007, wrote newspaper and magazine articles for 17 publications, fronted his own rock band, and produced Humphrey’s Concerts for more than two decades. In his page-turner of a memoir, Off My Rocker, Kenny presents an insider's view of a crazy life devoted to music.

Follow him on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/kenny.weissberg |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed