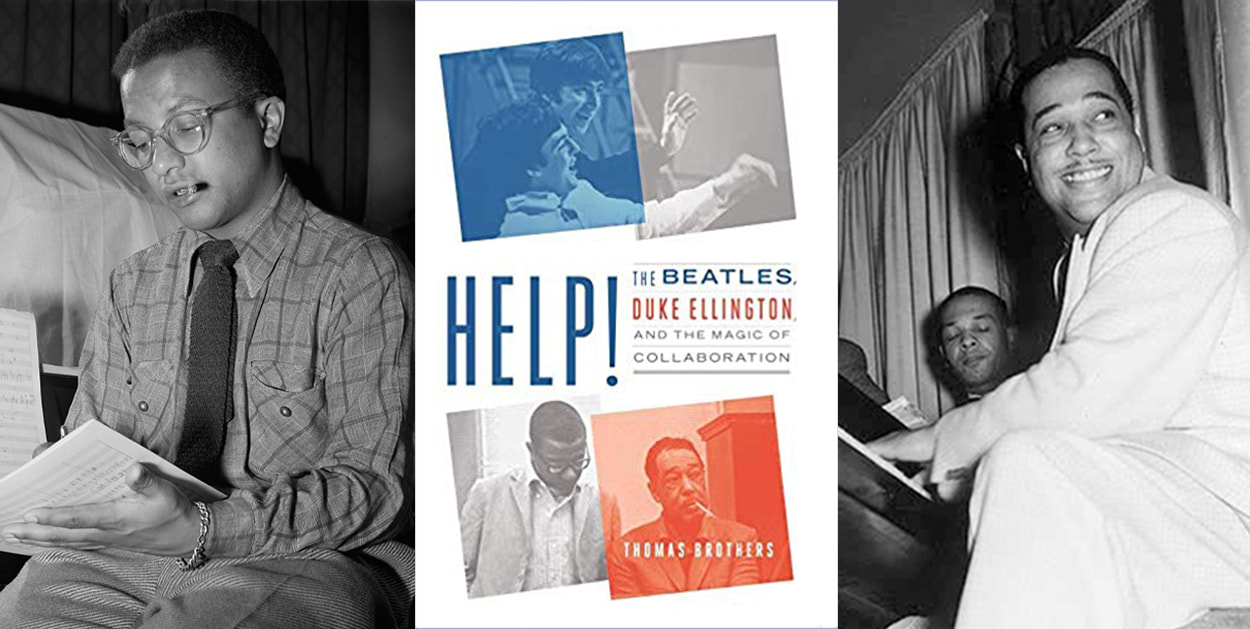

Brothers devotes one half of his book to Ellington, the other half to the Beatles. My review concerns only the former. The author concludes the Ellington section thus:

At age twenty-seven, the failed composer discovered a new way to generate music by extending material from his soloists through framing and conceptualizing, nipping and tucking, harmonizing, and arranging and enhancing with contrast and form. . . . [He got] the best of their arranging ideas, the best of their editing, the best of their creative use of timbre, and the best of their fully framed compositions.

And he didn’t give them credit.

As Brothers documents, with but a few exceptions, Ellington did not write the songs, instrumentals, and extended pieces we associate with him—some 1,500 copyrighted pieces. He borrowed fragments or fully formed melodies from his sidemen without giving them credit.

He poached from nearly everyone in the Ellington camp, from Bubber Miley, Otto Hardwick, Barney Bigard, Johnny Hodges, Cootie Williams, Ben Webster, Rex Stewart, Juan Tizol, Lawrence Brown to Billy Strayhorn.

And, yes, that would mean some of your favorite songs—“In a Sentimental Mood,” “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore,” “I’m Beginning to See the Light”—and many more were written by someone other than Duke.

And that goes for your favorite instrumentals, like “East St. Louis Toodle-O,” “Black and Tan Fantasy,” and “Cotton Tail”—way too many to mention here. For the complete story, I highly recommend Mr. Brothers’s well-researched and well-written book.

This is not to say that Ellington never composed anything of value on his own. He did, for example, the famous three-part introduction to “Mood Indigo,” “Solitude,” and “Amad” and “Depk” in the Far East Suite, but as Brothers makes clear, Duke’s compositions were the exception to the rule.

In addition, according to Brothers,

Noncrediting was part of Ellington’s ecosystem for sustained big-band success. First, it would have cost him massive streams of revenue [from lost song royalties], and second, it would have undermined his carefully managed image as a composer-genius unique in the sprawling field of jazz.

So why did his bandsmen all go along with it?

Security.

Ellington’s band was not only the most stable over those 40-plus years, but also—for most sidemen—the highest paying. Ellington’s ecosystem, as Brothers makes clear, included “giving raises and privileges to musicians who supplied their melodies, riffs, and pieces. . . . [Duke] preferred to keep the fluid dynamics of interactive creativity in the shadowy background.”

And for the most part, carping aside, his silent partners went along with it. A steady, well-paying job in a world-class orchestra was worth it.

The collective Ellington output remains unscathed; all that changes by the revelations in Help! is how we view Ellington. He is no longer the genius composer but the genius collaborator. Sadly, a lesser category with diminished importance and cachet than the former.

And it must be said, the new revelations do not tarnish in the least Ellington the conductor, pianist, talent scout, entertainer, agent, mastermind, and advocate.

An interesting exercise would be to assume that Ellington was the composer of every piece of music associated with his name. And then compare and rank the entire output with that of his American composer peers George Gershwin, Irving Berlin, Virgil Thomson, Jerome Kern, Cole Porter, Aaron Copland, Harold Arlen, Richard Rodgers, Hoagland Carmichael, and anybody else you would want to name.

I would rank the collective Duke at the top along with Gershwin and Rodgers.

As for Duke being, as is often said, jazz’s finest composer, does he now take a lesser place to Jelly Roll Morton or Fats Waller or Charles Mingus or John Lewis or anybody else?

All that can be said for certain, using contemporary terminology, is that Duke was CEO, COO, CFO, and President of Marketing and Public Relations of Ellington Inc. for over four decades.

CODA

According to Brothers, “Ellington’s career inevitably divides into two parts—before Strayhorn and after”—that is, before Strayhorn joined Ellington in 1939 and afterward.

But there was a third part—after Strayhorn’s passing in 1967 and before Ellington’s death in 1974—a seven-year period during which the maestro produced at least three major works: The Afro-Eurasian Eclipse, Latin American Suite, and New Orleans Suite.

Brothers did not evaluate or discuss this period, a shortcoming that could be addressed in the forthcoming paperback edition.

CODA CODA

It is my hope that Brothers’s in-depth look at collaboration in the Ellington realm will encourage other scholars to do the same for Duke’s peer composers mentioned above—George Gershwin, Irving Berlin, et al. Only then, can we reach a final judgment on Ellington’s compositional identity and practices.

To find out more about Thomas Brothers’s book Help!: The Beatles, Duke Ellington, and the Magic of Collaboration, click here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed