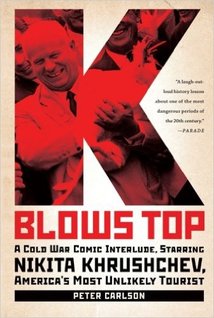

In his book, K Blows Top, author Peter Carlson offers a delightful retelling of the famed “Kitchen Debate” between then Vice President Richard Nixon and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, held in a model American home surrounded by a media scrum at the American National Exhibition in Moscow in July 1959.

The two combatants traded barbs over tract homes, washing machines, housewives, rockets, computers, and robots, with Nixon giving (almost) as much as he got. Only once, as Carlson summed it up, did the two agree on anything: "Hearing an American jazz band in the distance, Nixon remarked, 'I don’t like jazz music,' and Khrushchev replied, 'I don’t like it either.'" (1)

NIXON AND JAZZ. First, throughout the debate, Nixon mightily praised and staunchly defended everything American except jazz, that most democratic music. The political thing for him to have said was, “How do you like our American jazz?” His sparring partner would have answered the same, “I don’t like it.” And then Nixon could have said, “Well, maybe you’ll learn to like it someday.” Obviously, the politic thing to say eluded him, overwhelmed as he was by a distaste for the music.

Second, some 10 years later, after the vice president became President Nixon, he would ironically become the first president to venerate jazz by awarding the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor to Duke Ellington—the most articulate spokesperson, prolific composer, and honored personage in jazz for over four decades. Nixon did this, not because he had a change of heart (grew to like the music in the intervening years) but for other reasons, chief among them was his desire to trump the grandiosity of the JFK Camelot years with a glittering celebratory affair at the White House. And it was Nixon—and nobody else—that suggested Ellington be given the nation’s highest civilian honor.

On the night of the ceremony at the mansion—appropriately Duke’s seventieth birthday on April 29, 1969—and after a sumptuous banquet, speeches and a 90-minute all-star jazz concert followed by a jam session, Nixon told arts aide Leonard Garment, “If this is jazz, we should have more of it at the White House.” (2) Moreover, 11 months later, after another White House jazz event—by the so-called World’s Greatest Jazz Band—a reporter asked the president how he liked the music, and he replied, “I like jazz. It was an excellent band.” Ah, progress. From “I don’t like jazz “ to “I like jazz” in only 11 years—that’s progress. (3)

Thirteen jazz events were held during Nixon’s tenure, six for Heads of State (France, Germany, Iran, Italy, Ivory Coast, and Mexico). No invite was extended to the Soviet Premier. (4) Having been deposed (retired with pension) prior to Nixon taking office, Khrushchev would not have attended in any case. However, from his dacha outside Moscow, he no doubt took notice of Nixon’s doings and, wagging his head, thought, “Doesn’t like jazz, huh? Can’t believe a thing that guy says.”

CODA. Nikita Khrushchev accepted President Dwight Eisenhower’s invitation to tour the United States for two weeks in late summer 1959. Half the country, according to Peter Carlson, seemed eager to show the visitor the “real America”:

Trumpeter Louis Armstrong suggested that the Soviet premier visit a jazz club to experience “the swingin’ feel of freedom.” Sitting in his dressing room after a gig in Las Vegas, Armstrong said he’d love to play for Mr. K. “He’s a cat, man,” Satchmo said. “He’s a human being, like anybody else. And if a man don’t like music, he wouldn’t be in the position he’s got.” (5)

- Peter Carlson, K Blows Top: A Cold War Comic Interlude Starring Nikita Khrushchev, America’s Most Unlikely Tourist (New York: PublicAffairs, 2010), 28.

- Edward Allan Faine, Ellington at the White House, 1969 (Takoma Park, MD: IM Press, 2013), 179.

- Edward Allan Faine, The Best Gig in Town: Jazz Artists at the White House, 1969-1974 (Takoma Park, MD: IM Press, 2015), 80.

- Ibid., 139-44.

- Carlson, K Blows Top, 57.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed