In the first part of this blog series, we looked at two of the four jazz innovators who came to the fore in 1958—Miles Davis, John Coltrane. Here, we move on to the other two: Thelonius Monk and Ornette Coleman.

THELONIUS MONK

Thelonius Monk, a jazz icon dedicated to his art, finally received his long-overdue recognition in 1958. Monk, who today is regarded as a major composer almost on a par with Duke Ellington, languished in obscurity until 1957. This lack of recognition stemmed in part from the loss of his cabaret card in 1951 due to a questionable drug charge, which prevented him from working in New York City (the jazz capital of the world and his hometown). The neglect was also the result of his highly personal approach to the piano, misunderstood by many musicians and critics alike.

But his recordings didn’t go totally unrecognized. A handful of New York critics consistently championed his work. In 1957, after regaining his cabaret card, Monk played at the Five Spot Café in lower Manhattan six nights a week to capacity crowds. Musicians and critics began to spread the word.

Here was a pianist whose approach eschewed the modern and embraced the traditional, an unabashed melodist—albeit, a quirky one—who embellished and extended the melody like jazzmen of the past, yet sounded “far out,” more modern than modern. Here was a pianist not easily copied or understood at first hearing. As the jazz world soon learned, Monk’s music consisted of more than idiosyncratic, dissonant melodies.

The Five Spot gig was but a prelude to Monk’s discovery as a major jazzman. Some say “rediscovery” because of his early 1940s contributions to bebop, but the truth is that very few Americans had ever heard of him prior to 1958. Monk was profiled in DownBeat that year in an article headlined “Finally Discovered” and was awarded first place on piano—for the first time—in both the Critics and Readers Polls.

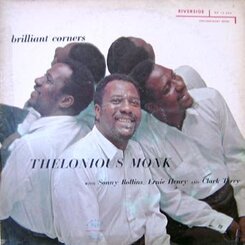

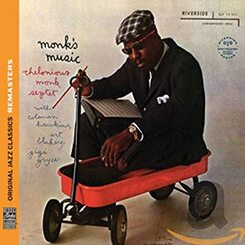

With Monk’s discovery, Riverside, his recording company since 1955, heavily promoted his early albums and recorded new ones, often with jazz greats, no doubt to confirm his newfound position within the jazz tradition. In 1959, Monk showcased his music in a big-band setting at a memorable Town Hall concert.

His 40-some composition legacy, which he essentially completed before his public discovery in 1958, equals that of any 20th-century composer.

ORNETTE!

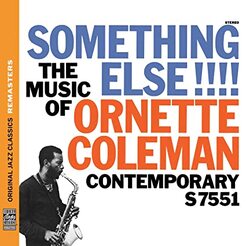

Ornette Coleman also came to prominence in 1958 with an album on the small Contemporary label entitled Something Else! The LP sounded like some quirky brand of bebop and received neither general critical nor popular acclaim, although the DownBeat reviewer gave it four and a half stars.

Ornette based his improvisations on the atmosphere or mood of a piece, deemphasizing the melody, the underlying harmonic structure, and the key. His approach to improvisation, not at first really understood by anyone, was variously labeled as modal, thematic, or intuitive. Ornette would later describe it as “harmolodic,” which, he said, “has as to do with the melody, the harmony and the rhythm all equal.”

While critics were labeling Coltrane’s music “anti-jazz,” they called Ornette’s “anti-music,” “chaos,” and worse. One critic said, “His is not musical freedom; disdain for principles and boundaries is synonymous not with freedom but with anarchy.” Ornette’s use of an occasional squawky white plastic alto saxophone didn’t help matters either.

While his detractors were legion, his supporters (who swore from the start he was a genius) were among the bigger lights in jazz music and criticism—Leonard Bernstein, Nat Hentoff, John Lewis, Gunther Schuller, and Martin Williams, to name a few.

One of the most controversial of jazz icons to this day, Ornette has never received the public acclaim or the financial reward the others have, even belatedly. In time, he was grudgingly recognized as a major innovator in jazz for launching free jazz and influencing many musicians, including Coltrane.

LASTING CONTRIBUTIONS

The fact that four major innovators of jazz—Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Thelonius Monk, and Ornette Coleman--came to the fore in 1958 is quite astonishing. Each, it could be said, was a tonal innovator. No one before or since has sounded like Miles, Coltrane, Monk, or Ornette on their respective instruments. It could also be said that each had far-reaching influence—another mark of innovation. Each, in his own way, was a composer, with Monk the most unique; and they all pointed the way to more, not less, freedom in jazz.

More significant, however, are their lasting contributions to musical improvisation, the key ingredient in jazz. Miles blazed the way for improvisations on scales and modes; Monk, on melody; Coltrane, on harmonic structure and eventually modes; and Ornette, on atmosphere or mood of a piece.

While not one of them was the first or only musician to explore these concepts in jazz, they all developed them to the point of universal admiration and recognition in the context of later 20th-century music.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed