Ticket prices are reasonable, and there is ample free parking. Artists are likewise treated with respect in a comfy greenroom: a separate dressing room with a washer and dryer.

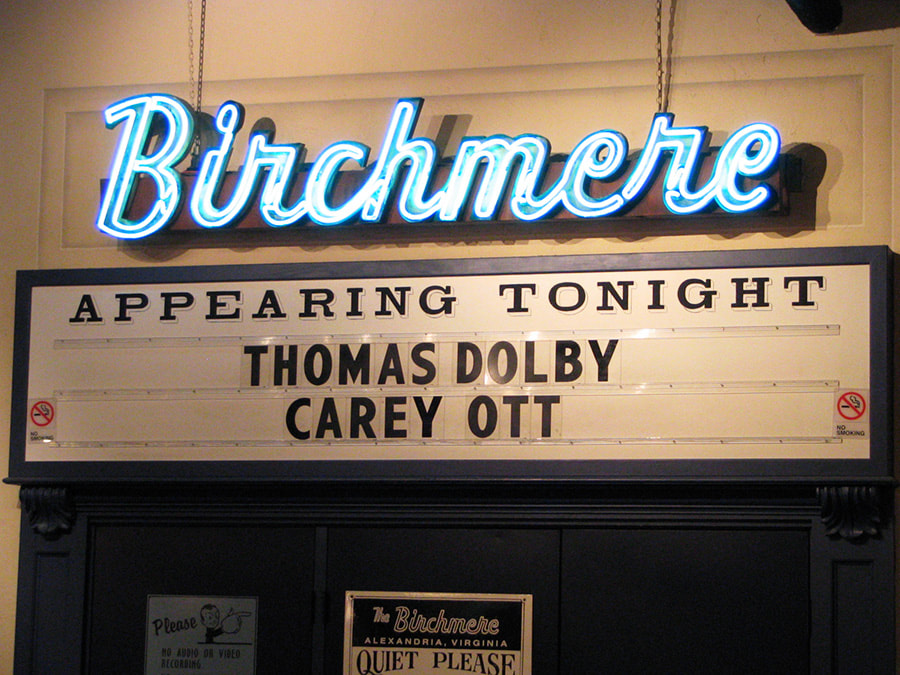

The Birchmere premiered as a bluegrass music club, and its history evolved into diverse entertainment, which is an understatement: can you believe bluegrass, country, western, folk (both European and American), rock, blues, R&B, gospel, funk, Celtic, zydeco, pop, and jazz (the focus of this blog)?

The Birchmere presents one or two artists just about every night of the week to mostly sold-out crowds. In sum, an iconic room with an excellent sound system that facilitates the connection between artists and the audience.

In their book, All Roads Lead to the Birchmere: America’s Legendary Music Hall, authors Gary Oelze (original and current owner) and Stephen Moore (musician, writer) devote a chapter to jazz that they call “Jazz Hands.”

The chapter profiles the 12 artists listed below. Biographical information is provided, along with a photograph taken at the club, an anecdote or two about their experience, and audience reaction. Another list is provided (names only) of artists who have appeared at the hall over the years.

Any jazz fan scanning the lists of artists below would likely conclude “pretty damn good, especially for a club that’s not a jazz club per se”:

| Joe Sample (Keyboards) Tuck and Patti (Guitar and Singer) Chick Corea (Keyboards) [3] McCoy Tyner (Keyboards) Ottmar Liebert (Guitar) [20] Herb Albert (Trumpet) [5] Ramsey Lewis (Keyboards) Herbie Hancock (Keyboards) George Duke (Keyboards) Dweezil Zappa (Guitar) [4] Jean Luc Ponty (Violin) [2] Candy Dulfer (Saxophone) [6] Note: [ ] number of times at Birchmere |

Other jazz artists who appeared at the Hall over the years include Gato Barberie (saxophone), Hugh Masekala (trumpet), Blue Note 75 All-Stars (tribute band), Jeff Lorber (keyboards), Kenny G. (saxophone), Najee (saxophone), Pieces of a Dream (jazz fusion), Preservation Hall Jazz Band (DixielandDixieland), Rachel Ferrell (singer), Robbin Ford (guitar) among many others.*

While jazz was not the dominant musical genre played at the Birchmere by any means, it was fairly represented. A decent mix of known stars and up-and-comers could count on their performances being well advertised on the club marquee, in well-placed newspaper ads, on the radio, and in recent years on the internet to followers numbering in the hundreds of thousands.

The result: well-attended shows and an uptick in name recognition. The latter is not to be overlooked. Birchmere attendees are known to be a mite more open-minded than most fans—they will attend an event outside their genre comfort zones simply because if it’s at the Birchmere, it has to be good. Not bad for a music hall not necessarily known as a jazz club.

A gig at the Birchmere is a resume-topper second only to Madison Square Garden and a few other performances spaces. In an era when jazz is not as popular as it once was—dropping from 13 percent in recorded music sales in 1960 to 1 percent today—thank goodness, the road to America’s Legendary Music Hall is still open and well-paved.

CODA

I highly recommend the referenced book below. No matter your specific musical preferences, you’ll come across numerous artists and songs that helped define your life one way or another. Moreover, I guarantee you’ll learn interesting facts about artists and songs you never knew before.

| *Gary Oelze and Stephen Moore, All Roads Lead to the Birchmere: America’s Legendary Music Hall (St. Petersburg, Florida: Booklocker.com Inc., 2021), 395–403. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed