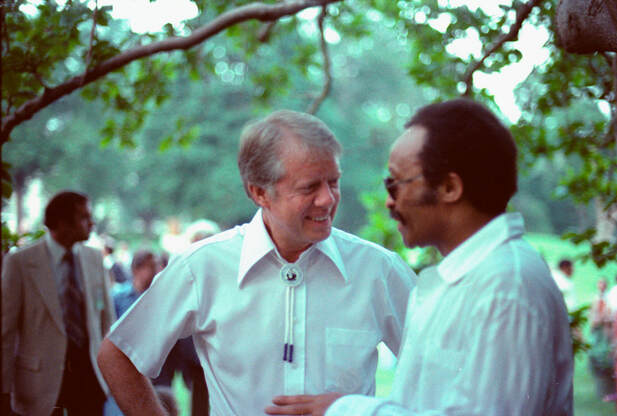

But others claim that President Carter’s South Lawn gathering some nine years later, billed as the first White House jazz festival, tops the Duke event by a country mile.

Frankly, it’s hard to disagree: Carter’s introductory speech and the gasping, jaw-dropping lineup of jazz stars were exemplary.

On June 18, 1978, Carter stepped up on the specially erected stage on the South Lawn of the White House and—facing the 800 people gathered before him (musicians and their families and invited guests)—gave the most enlightened and heartfelt speech by any US president on America’s own music. And he did so extemporaneously:

|

You are welcome to the first White House jazz festival. I hope we have some more in the future. This is an honor for me—to walk through this crowd and meet famous jazz musicians and the families of those who are no longer with us, but whose work and whose spirit and whose beautiful music will live forever in our country. If there ever was an indigenous art form, one that is special and peculiar to the United States and represents what we are as a country, I would say that it’s jazz. Starting late in the last century, there was a unique combination of two characteristics that have made America what it is: individuality and a free expression of one’s inner spirit. In an almost unconstrained way, vivid, alive, aggressive, innovative on the one hand, and the severest form of self-discipline on the other, never compromising quality as the human spirit bursts forward in an expression of song. At first, this jazz form was not well accepted in respectable circles. I think there was an element of racism perhaps at the beginning, because most of the famous early performers were black. And particularly in the South to have black and white musicians playing together was not a normal thing. And I believe that this particular form of music—of art—has done as much as anything to break down those barriers and to let us live and work and play and make beautiful music together. And the other thing that kind of separated jazz musicians from the upper levels of society was the reputation jazz musicians had. Some people thought they stayed up late at night, drank a lot, and did a lot of carousing around. And it took a few years for society to come together. I don’t know. I’m not going to say, as President, whether the jazz musicians became better behaved or the rest of society caught up with them in drinking, carousing around, and staying up late at night. But the fact is that over a period of years the quality of jazz could not be constrained. It could not be unrecognized. And it swept not only our country, but is perhaps the favorite export product of the United States to Europe and in other parts of the world. I began listening to jazz when I was quite young—on the radio, listening to performances broadcast from New Orleans. And later when I was a young officer in the navy, in the early ’40s, I would go to Greenwich Village to listen to the jazz performers who came there. And with my wife later on, we’d go down to New Orleans and listen to individual performances on Sunday afternoon on Royal Street, sit in on the jam sessions that lasted for hours and hours. And then later, of course, we began to learn the individual performers through the phonograph records and also on the radio itself. This has had a very beneficial effect on my life. And I’m very grateful for what all these remarkable performers have done. Twenty-five years ago, the first Newport Jazz Festival was held. So this is a celebration of an anniversary and a recognition of what it meant to bring together such a wide diversity of performers and different elements of jazz in its broader definition that collectively is even a much more profound accomplishment than the superb musicians and the individual types of jazz standing alone. And it’s with a great deal of pleasure that I—as president of the United States—welcome tonight superb representatives of this music form. Having performers here who represent the history of music throughout this century, some quite old in years, still young at heart, others newcomers to jazz who have brought an increasing dynamism to it, and a constantly evolving, striving for perfection as the new elements of jazz are explored. George Wein has put together this program, and I’d like to welcome him and all the superb performers whom I met individually earlier today. And I know that we all have in store for us a wonderful treat as some of the best musicians of our country—of the world—show us what it means to be an American and to join in the pride that we feel for those who’ve made jazz such a wonderful part of our lives. Thank you very much.[1] |

He next touched on two of the several reasons that slowed acceptance of jazz as an art form in this country—namely, racism and a musical elitism that categorized jazz as roadhouse or speakeasy entertainment.

But it was Carter’s personal recollection of his early jazz experiences that piqued the most interest. In fact, to many, it came as a shock: Jimmy Carter?! The peanut farmer from Georgia known to be a classical devotee (by those in the know) or maybe a Southern rock enthusiast (by those not in the know)—was a jazz fan? And an avid one at that! Who knew?

And the lineup of talent on the South Lawn that memorable day was beyond “Wow!” From the daughter of bluesman W. C. Handy and 90-year-old pianist Eubie Blake to avant-gardists Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor, and everyone in between. Here’s a full list:

|

Piano

|

Saxophone

|

Trumpet

|

Drums

|

|

Eubie Blake

Chick Corea Gil Evans Herbie Hancock Dick Hyman John Lewis George Russell Billy Taylor Cecil Taylor McCoy Tyner Mary Lou Williams Teddy Wilson |

Benny Carter

Ornette Coleman Stan Getz Dexter Gordon Illinois Jacquet Gerry Mulligan Sam Rivers Sonny Rollins Zoot Sims |

Doc Cheatham

Roy Eldridge Dizzy Gillespie Joe Newman Clark Terry |

Louis Bellson

Denardo Coleman Jo Jones Max Roach Tony Williams |

|

Bass

|

Guitar

|

Vibes

|

Singers

|

|

Ray Brown

Ron Carter Milt Hinton Charles Mingus |

George Benson

|

Lionel Hampton

|

Pearl Bailey

Katharine Handy Lewis |

He acknowledges “the big event held on the South Lawn” as “the best party we’ve ever had—the Newport Jazz Festival twenty-fifth anniversary. About 800 people came, and we had a collection of jazz musicians that was really remarkable.”

But that’s it, except for the anecdotes about himself and his daughter: “I went on stage with Dizzy Gillespie, and joined him in a rendition of ‘Salt Peanuts.’ It was a high point in my life when the New York Times complimented my singing,” and “Amy performed on the violin, which was a real hit.”[2]

The president’s ardor for the European import is abundantly clear in White House Diary as he rhapsodizes about classical performers who came to the White House—pianist Vladimer Horowitz, opera singers Roberta Peters and Leontyne Price, and cellist Slava Rostropovich—and takes forays with First Lady Rosalynn to hear classical expositions at the Kennedy Center and Metropolitan Opera.

He also tells us (which many knew at the time): “In the inner White House office, we established a high-fidelity sound system, and for eight or ten hours a day I listened to classical music.”[4]

We have the music for the first event available from Blue Note Records in 1969 All-Star White House Tribute to Duke Ellington. Not so the latter. NPR recorded the music but has not released it. So what’s the hold up?

- Recording courtesy of the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum.

- Jimmy Carter, White House Diary (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010), 136, 202.

- Ibid., 136.

- Ibid., 12.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed