Most often identified with the jazz avant-garde of the 1960s, trombonist Roswell Rudd, together with West African (Malian) musicians, formed a cross-cultural ensemble to create an original sound neither jazz nor traditional African.

The result: MALIcool.

Rudd’s usual thick trombone sounds, growls, smears, and boozy blats along with his warm tone dances its way among the sonic wonderland of Malian instruments — kora (12-string harp), ngoni (plucked lute), balaphone (Afro vibes), guitar, bass, and djembe (hand drum).

After reconciling the two musical systems (7-tone open form with 12-tone closed form), arrangements for the most part were deliberately sparse, leaving room for everyone to improvise.

The album’s songs could not have been more varied: Thelonious Monk’s “Jackie-ing,” a traditional Welsh folk song, a re-imagining of Gershwin’s “Summertime,” and Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy,” and several African traditional numbers.

A close listen to the album’s ten tunes, specifically to the strings (kora, ngoni, and guitar) will let you know where country blues came from, ditto the balafon, where swing-era vibist Lionel Hampton came from.

John Ephland of DownBeat magazine wrote: “Jazz purists will no doubt scoff at this meeting of musical souls. No matter how you slice and dice it, this music, modest at times, is still a ballsy bit of panache, a marriage of seemingly disparate worlds into something that works.”

I agree, besides, most jazz purists did not scoff. Released in 2002, MALIcool made it onto various Top Ten lists of the year.

Drummer/arranger John Hollenbeck has put together a stunning album with cohorts Gary Versace (piano/organ), Kate McGarry and Theo Beckman (vocalists), and the 16-piece Frankfort Radio Big Band (five winds, four trumpets, four trombones, three rhythm — drums, electric and acoustic guitar, and bass.)

After a first listen, you will like Hollenbeck’s songs too, starting with the majestically arranged “Wichita Lineman.” The Jimmy Webb classic begins with a softly picked guitar line over a clarinet/flute chorus.

The crystalline pure voice of McGarry sings the first verse. An instrumental interval precedes Beckman’s take on the second verse before a rhythmic chording of piano, flute, and winds support a lengthy electric guitar solo.

The prominent role Hollenbeck assigns to the guitar here is perhaps a tribute to Glen Campbell’s and Wrecking Crew regular Carol Kaye’s guitar playing on the original hit version. Additional instruments and the vocalists enter the fray, a new but related melody develops, and the guitar makes a final statement before the coda: a gorgeous instrumental passage with voices in harmony and flutes a flutter.

John Kelman (All About Jazz) concluded: “It’s a song that’s been covered many times before but never so cinematically.”

Next up: “Canvas” by English singer-songwriter Imogen Heap from her 2009 album Ellipse.

The track begins with a riffing guitar followed by an instrumental statement of the melody. McGarry enters alone and then is doubled by Beckman giving voice to rather a singular melody that leads to a magnificent trombone solo. Hollenbeck’s drumming is persistent throughout, upping the tempo and the song’s energy at the close.

John Kelman again hits the nail on the head when he wrote, “If Wichita Lineman” is cinematic then Hollenbeck’s arrangement of Webb’s ‘The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress’ is positively IMAX.”

The arranger’s take on this lesser-known Webb tune is a sprawling 14-minute wall of compelling sound. The piece begins with just McGarry’s voice and piano before a layer of flutes and winds softly insinuate themselves into the arrangement.

The tempo picks up, and then guitar, drums and other instruments join in, piano becomes more dominant, volume steadily builds, drums more active. McGarry and Beckman join in, build, build, voices ooohing and aaahing.

Then a cooldown led by a lone clarinet before the entire orchestra climbs back up the aural staircase to greet a tenor saxophone solo at the top.

Beckman re-enters voicing the melody. McGarry joins him as the full orchestra roars into a symphonic ending with wind instruments mirroring the violins. Trust me, this is better heard than read.

“Man of Constant Sorrow,” whew!

The traditional folk tune’s tempestuous intro — low growly brass and winds and Hollenbeck’s tumultuous drums — lead to a second section of quick-strummed acoustic guitar and Beckman’s delivery of “Sorrow’s” first verse with McGarry’s repeating last line.

A killer lengthy tenor sax solo follows as Hammond organ punctuates the never-wavering strumming and drumming. Beckman sings the second verse.

McGarry repeats the last line as before. Alto sax solo follows, other instruments join in, low horns and organ chug away along with Hollenbeck’s constantly churning drums.

Beckman sings the final verse, and with McGarry, sings the last line “Meet you on that golden shore” 10 times! For the coda, organ, full orchestra, drums, vocalists go crazy, or as one critic put it, “Go Dixieland in the sixth dimension.” In other words, go free, like maybe Charlie Haden and the Liberation Orchestra.

Who could have imagined such an ending for a circa 1900 mountain folk song? John Hollenbeck, that’s who.

Free jazz originator Ornette Coleman’s “All My Life” originally sung by Indian singer-songwriter Asha Puhli in Coleman’s Science Fiction (1972) album is given a much different treatment by Hollenbeck.

Vocal honors to Kate McGarry, and what a lovely melody it is. At the outset, she sings over simple

piano accompaniment before the orchestra enters with a paraphrase. McGarry continues on with light orchestra backing, passing the baton to the band for a round of overlapping solos.

Then, with busy drums underneath, singer and orchestra carry the melody together, with the latter becoming progressively more dominant. The song ends with multiple instruments soloing.

Through it all, Ornette’s attractive melody is never far from listeners’ ears.

“Fall’s Lake,” a song from the indie-electronic artist Nubukazu Takemura featuring clarinet and distorted-sounding vocalists is not as interesting as the others. Too arty.

Hollenbeck’s song “Chapel Falls” closes the album in a relaxed mood. It starts with a repetitive piano figure underneath a sing-songy melody that is subsequently repeated by various sections of the band creating an ear-catching soundscape.

In essence, a mid-tempo toe-tapper, a good closer.

This is not, repeat not, a novelty album — far from it.

Pop/country singer-pianist Hornsby can indeed play jazz piano, especially in the company of heavyweights Christian McBride (bass) and Jack DeJohnette (drums).

The trio tackles familiar themes from the jazz songbook — “Solar” (Miles), “Giant Steps” (Coltrane), “Straight No Chaser,” (Monk), “Un Poco Loco,” (Powell), “We’ll Be Together Again,” (Fischer/Lane), and two Hornsby originals. The album’s standout track is his “Camp Meeting”: a slow-building churchified romp worthy of FM radio play. The interplay between pianist and bassist is extraordinary.

Jazz Times critic Steve Greenlee commented, “The music stretches and contracts, it races, it gallops and It rumbles. It sounds like Keith Jarrett and Chick Corea and Bill Evans, all of them and none of them.”

Precisely, it sounds like Bruce Hornsby.

In my opinion, the uniquely gifted Andrew Hill (1931–2009) never received his due as a jazz composer or pianist beyond the narrow jazz critical elite.

Regarding the former, people are quick to name Duke Ellington, Billy Stayhorn, Tadd Dameron, Charles Mingus, John Lewis, Thelonious Monk, Bill Evans, Benny Golson, Wayne Shorter for example, but never Andrew Hill.

Similarly, when bop and post-bop pianists are discussed, people will offer up the likes of Bud Powell, Horace Silver, Mal Waldron, Paul Bley, Cecil Taylor, and Carla Bley but never Andrew Hill.

This, even though he recorded 51 mostly highly rated albums (31 as leader featuring top-flight musicians) and even though he received many prestigious awards, for example DownBeat Hall of Fame, NEA Jazz Master, Jazz Journalist Association Lifetime Achievement, and the first Doris Duke Foundation Award for Jazz Composers. Andrew, it appears, was about as famous as Whistler’s father.

One last sad note, in Whitney Balliett’s voluminous 880-page Collected Works: A Journal of Jazz 1952–2001 there is not one mention of — you guessed it — Andrew Hill.

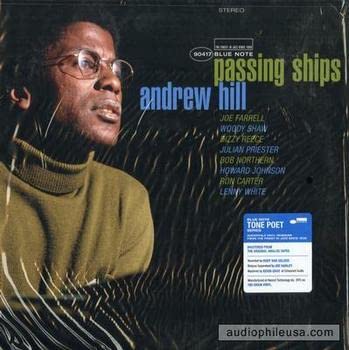

As for me, I fell in love with his 1960s Blue Note LPs (Black Fire, Smokestack, Judgement, Point of Departure, Compulsion) and one, Passing Ships, recorded in 1969 that was belatedly released on CD 34 years later.

Andrew surrounded himself with rhythm (Ron Carter, bass, Lenny White, drums) and six horns: (Woody Shaw and Dizzy Reese, trumpets), (Julian Preister, trombone), (Bob Northern, french horn), (Howard Johnson, tuba and bass clarinet), (Joe Farrell, soprano and tenor, and other winds) — a nonet performing seven original compositions.

This is a personal favorite even though it has obvious flaws. The recording and mixing are sub-par and Andrew’s arrangements for large ensemble are, while ambitious, sloppily executed at times (perhaps due to inadequate rehearsal time).

Andrew compensated for this by, as always, his appealing quirky, idiosyncratic compositions and outstanding soloing by everyone, especially Farrell, Shaw, and himself. Listen to the first tracks “Sideways,” “Passing Ships,” Plantation Bag,” and “Noontide.”

Ask yourself whether anyone of these compositions could make a hard bop playlist along with tracks by hard boppers Art Blakey, Horace Silver, Lee Morgan, Benny Golson, Jackie McLean, Donald Byrd, Bobby Timmons or Cannonball Adderley. You bet, most would, especially “Plantation Bag.”

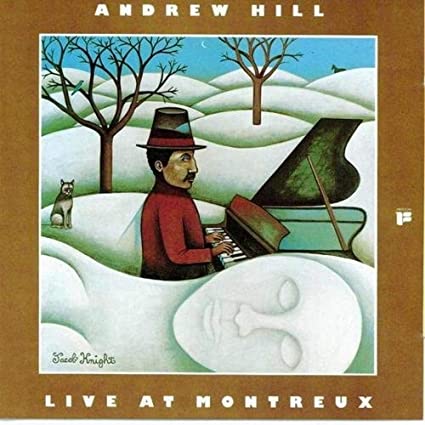

Live at Montreux (1975) is an excellent introduction to Andrew the solo pianist starting with the jagged, jaunty and delightful “Snake Hip Waltz” followed by the darker but still accessible “Nefertisus.”

The longest track on the album is the abstract and challenging yet entertaining eighteen-minute “Relativity.”

The pianist’s stylistic influences — stride, boogie-woogie, post-bop, and avant-garde are on full display. The album concludes with Andrew’s five-minute sketch of the melodic contours of Duke Ellington’s supreme contribution to the American hymnal “Come Sunday.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed