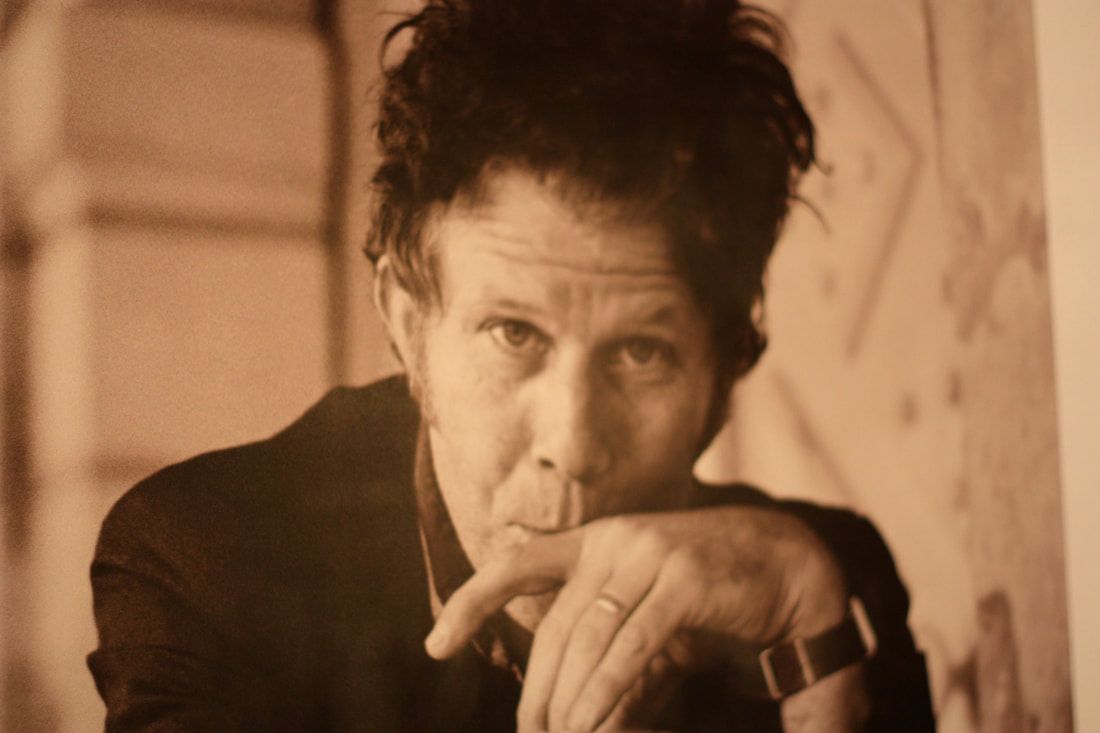

The voice alone is beyond category and, despite best efforts by journalists over the years, beyond accurate description. It has been variously characterized as a scabrous rasp, garbage crusher, low growl (like Satchmo without the joy), smashed foghorn, bullfrog croak, hungover whisper, hemorrhage, cross between a mellifluous baritone and a heavy equipment breakdown, and born old smoking.

Waits himself has said, “My voice is still a barking dog at best.”

As his fans know only too well, Waits career comes in two parts: the early years (the “complacent years,” as Tom has called them) through 1982 and everything thereafter (the “adventurous years”). No one would disagree with Tom here. Critics have called this later music disembodied ham-radio, savage-yard symphonies, lunatic cabaret, taxonomically confounding vaudeville, and stone-age blues.

But the early years—the years when we first got to know him—were anything but complacent. Sorry, Tom, but many of your fans respectfully disagree. Except for the first album, Closing Time (Elektra, 1973), the music from this period is a mélange of jazz, heart-throbbing ballads, and neo-beat poetry.

As the New Yorker magazine said in 1976, his soulful serenades reflected a Kerouac/Bukowski–like landscape

that is bleak, lonely, contemporary: all-night diners, cheap hotels; truck stops; pool halls; strip joints; Continental Trailways buses; double-knits; full-table rail shots; jumper cables; Naugahyde luncheonette booths; Foster Grant wraparounds; hash browns over easy; glasspacks and overhead cams; dawn skies “the color of Pepto-Bismol.” His songs—mostly blues—are not everybody’s cup of Instant Nestea, but they range from raunchy to beautiful. [1]

Almost all of his songs relied on pretty melodies, and some were unabashedly romantic. Go back and listen to his early albums, The Heart of Saturday Night (Elektra, 1974) through to Heartattack and Vine (Asylum, 1982). There are one or two love songs on each and every one—songs that wife Kathleen Brennan would call grand weepers (as opposed to grim reapers, the flip side of the Waits coin).

One from the Heart corked the early-period bottle in 1982. This movie and soundtrack album, like no other in the Waits oeuvre, illuminates the romantic facet of the Waits diamond. Tom got a huge assist from two unlikely sources—film director Francis Ford Coppola and the serendipitous, genre-busting addition of country singer Crystal Gayle, who, with her pure country voice, limned Waits melodies better than he could himself and, in duets with Tom, wedded that tear in her throat with the gravel in his.

In the spring of 1980, Waits learned that director Coppola, who had just released Apocalypse Now, wanted him to score his latest film, a romantic trifle about Hank (Frederick Forrest) and Frannie (Terri Garr), a couple whose relationship had soured. They drift apart and wind up in the arms of exotic new partners (played by Nastassja Kinski and Raul Julia), but of course get back together again.

This lover’s tango is set against the glowing backdrop of a Las Vegas Strip that Coppola had constructed on a studio soundstage at a horrendous cost (the same studio where Michael Powell had shot his fantasy The Thief of Baghdad—Coppola’s favorite film—40 years before). Francis did not conceive of Heart as a traditional Hollywood musical; none of the stars would actually sing.

He wanted a kind of running lyrical explanation to move the story forward. Waits would write songs that expressed the inner feelings of the characters; Tom would sing Hank and (initially) Bette Midler would sing Frannie. It was Waits’s duet with Midler on Foreign Affairs (Elektra, 1977) that inspired Coppola’s vision: a lounge operetta with piano, bass, drums, strings, jazz horns, and vocal commentary.

Waits had contributed songs to films before, Stallone’s Paradise Alley and Altman’s A Wedding among them, but Heart was an offer he couldn’t refuse. Coppola had put the entire score in his hands and told him: “Anything you write that deals with the subjects of love, romance, jealousy, breakups can find its way into the film.”

Waits elaborated:

There was never any gospel script. There was a blueprint, a skeleton . . . Before I started writing anything, I met Francis in Las Vegas. In a hotel room, he took down all the paintings from the walls and stretched up butcher paper like a mural. Then he sketched out sequences of events and would spot, in very cryptic notations, where he wanted the music. I was able to get an idea of the film’s peaks and valleys. [2]

Waits first enlisted long-term collaborator Bones Howe, who had produced and managed sound on his first six albums. Together they assembled an all-star cast of Hollywood musicians, mostly jazz guys they had worked with before—notably, trumpeter Jack Sheldon, tenor saxophonist Teddy Edwards, and drummer Shelley Manne.

Today “legendary” often appears before Sheldon’s name; due in part to his prominent long-running gig on the Merv Griffith Show and his own network TV show, Run Buddy Run. But it is his signature trumpet sound—lyrical, mid-range, striving—that has brought him accolades. His playing is sometimes mistaken for the early-career, romantic excursions of trumpeter Miles Davis.

Teddy Edwards, a saxophonist in the mold of Dexter Gordon (but mellower) simply got better as he got older, and was playing at his peak at the time of the Waits recording.

Widely admired for his crisp, precise sound and his ability to create a colorful tonal palette from his drum kit, Shelly Manne was a favorite of Waits, particularly for his drum work behind Peggy Lee on “Fever.” Manne played drums on two previous Waits albums, and their collaboration on “Pasties and a G-String” and “Barber Shop” are word-jazz classics.

Jazz pianist/vibist Victor Feldman and organist Ronnie Barron, who had appeared on Waits most recent album, came along for the ride, as did Waits newcomers—jazzmen all—vibraphonist Emil Richards, drummer Larry Bunker, and pianist Pete Jolly, who would man the piano chair so Tom could concentrate on his singing. Lastly, as he did on two recent Waits albums, Bob Alcivar arranged and conducted the string orchestra.

But Heart’s female voice proved to be elusive. Midler wasn’t available. Then God intervened. Kathleen Brennan (who later became Waits's wife) suggested country singer Crystal Gayle, the younger sister of Nashville legend Loretta Lynn. Crystal had 10 albums to her credit and had broken out nationally with her crossover mega hit in 1978: “Don’t It Make My Brown Eyes Blue” (eventually, astonishingly, one of the 10 most performed songs of the 20th century).

Her voice was undeniably sumptuous (but soulless some said) and seemingly at odds with Waits's grizzled growl and the urban squalor of his whiskey-soaked compositions.

This didn’t faze Kathleen. She’d recently heard Crystal’s rendition of the Julie London standard “Cry Me a River” off her 1978 release When I Dream (United Artists Records) and was impressed with the strength and purity of the young singer’s voice.

Check out next month’s blog—part 2—for a list of Waits’s 12 songs in this most underappreciated movie soundtrack, along with the reasons for the film’s disappointing failure at the box office.

- James Stevenson, “Blues,” The New Yorker, December 27, 1976, anthologized in Mac Montandon, Innocent When You Dream: The Tom Waits Reader (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2005), 20.

- Jay S. Jacobs, Wild Years: The Music and Myth of Tom Waits (Toronto: ECW Press, 2006), 105.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed