Mother Nature, in the form of fog, shivery temperatures, and intermittent tropical rain bursts, rendered the 1967 edition unlikely to make anyone’s NJF top 10 list. Still, the show went on with the usual cornucopia of musical acts and thematic groupings, as summarized below from reports by attending critics Whitney Balliett [1], Burt Goldblatt [2], and Dan Morgenstern [3].

June 30

The first day began with a “History of Jazz” lineup, although jazz critic Balliett likened it to a parade of pianists: Willie “the Lion” Smith, Earl Hines, Count Basie, Thelonius Monk, and John Lewis.

The first “History” group, led by percussionist Michael Olatunji, represented Mother Africa, which quickly gave way to Chicago with Earl Hines playing arrhythmic whirlpools and upper register single note jubilations (Balliett), leading to the New York Stride of Willie “the Lion” Smith and his booming irregular chord patterns, and rifle-shot single notes.

Count Basie (and associates) resurrected the sound of Kansas City, the pianist audible only in short solos behind the horn players. The “History” lesson continued with the 1940s bebop kings of New York: trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, sax player James Moody, vibist Milt Jackson, pianist Thelonious Monk, bassist Perch Heath, and drummer Max Roach.

Balliett judged their performance disappointing save for Monk; he also praised John Lewis’s graceful and thoughtful approach to the piano. To complete the stroll down “History” lane, the first day’s concert concluded with saxophonist Albert Ayler’s quartet, the only “New Thing” group to appear at the 1967 festival after a somewhat controversial avant-garde breakout the previous year by saxophonist Archie Shepp.

July 1

The afternoon concert was labeled “The Five Faces of Jazz,” or the five ethnic influences on jazz, or better said, contributions from five jazz musicians from other countries—namely, guitarist Gabor Szabo of Hungary, Albert Manglesdorf of Germany, Michael Olatunji of Nigeria, Luis Enrique of Brazil, and Nobuo Hara, leader of the Japanese Orchestra Sharps and Flats.

Weatherman Balliett reported that the fog had been doing “the mazurka up and down Narragansett Bay all afternoon and [by nightfall] it circled once about the town and fell asleep,” along with much of the night’s concert that began with Herbie Mann on flute, Roy Ayers on vibes, and Charles Ganimian on electric oud.

This outfit presented a different perspective on what is and what isn’t jazz. Pianist Earl Hines slipped in with his usual outstanding set of classics, joined by Budd Johnson on soprano saxophone, but Newport Festival chronicler Goldblatt as well as critic Morgensten found it hard to fathom why the pianist was inserted in a lineup of relatively modern stars.

The John Handy Quintet (vibes, guitar, bass, drums and the leader’s alto sax) plodded through two endless numbers. Nina Simone, who sang at the previous year’s concert, got hung up in a couple of interminable laments about loose men and fast women.

Steady NJF presence Dizzy Gillespie appeared with his quintet and did four by-rote numbers, but the oddest disappointment in Balliett’s view was the Gary Burton Quintet with Larry Coryell on electric guitar that reached for a distillate of jazz and rock and roll but failed to grasp either one.

Not to be surpassed, Morgenstern rhapsodized: his solo was an eruption, a phenomenon, a staggering display of superhuman endurance, co-ordination and control. It was an event in defiance of nature, and it is safe to say that no other drummer (or human being) could ever match it. Whew!

July 2

The afternoon concert began with the Japanese Sharps and Flats Big Band that Balliett characterized as a formidable cross between the late Jimmy Lunceford and early Stan Kenton bands, and its soloists suggested trombonist J. J. Johnson, trumpeters Art Farmer, and Clifford Brown, plus drummers Gene Krupa and Louis Bellson.

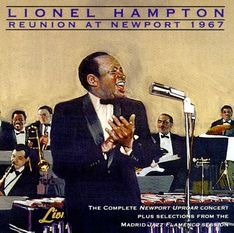

The main event was a vibraphone workshop—Bobby Hutcherson, Gary Burton, Red Norvo, and Milt Jackson, along with Lionel Hampton (believe it or not) making his Newport Jazz Festival debut.

According to Balliett, Burton sent up a ghostly unaccompanied ballad that was all willows and Debussy; Norvo produced a creditable (Cole Porter’s ) “I Love You,” and ended with his heavy mallet shtick—“slapsticks”—clumping around the keyboard like a slow-motion tap dancer.

Hampton unloaded his customary two-by-fours on a feverish “How High the Moon.” The audience kept interrupting him with bursts of applause. Hutcherson jammed a hundred notes into each measure on “Softly as in a Morning Sunrise,” and Jackson maintained his flowing lyric cool on “These Foolish Things.”

All five vibists got together for the closing “Hamp’s Boogie-Woogie,” accompanied by heavy rain. With a flood of perspiration running down their faces, Hamp and his colleagues took a bow to a cheering, smiling audience.

Goldblatt, more smitten than Balliett, called the workshop a Festival peak. Morgenstern said it was Newport at its best, the kind of happening that jazz festivals exist for.

There was an interpolated guest pianist in the midst of the workshop, much like Hines on the prior day’s evening concert, and the critics were none too happy about it. This time it was Billy Taylor, who captured the small, two thousand-member audience with his tremendous drive over an hour-long performance.

Unofficial weatherman Balliett reported that the rain for the evening was still reeling in low and cold at eight when the show began. He concluded all could have stayed home, summarily dismissing the night’s acts—Bill Evans Trio, Max Roach Quartet, Woody Herman’s Big Band, and the Miles Davis Quintet.

Goldblatt stayed the course and found much to like. Even with rain and sound system problems, he declared Max Roach’s unaccompanied drum solo, “It’s in Five,” the high spot of the evening and probably the whole Festival. Apparently, he was struck by the drummer’s individualistic clarity for sounds, giving new dimension and sensitivity without ever pounding (a là Buddy Rich, but he didn’t say).

Morgenstern followed suit: a masterpiece of musical intelligence and instrumental skill—perhaps the greatest musical drumming this listener has witnessed.

In 1966, Newport Festival Organizer George Wein introduced avant “New Thing” music for the first time. In 1967 it was rock music by the Blues Project—some of the group would go on to form the first rock-oriented jazz group, Blood, Sweat, and Tears.

Morgenstern felt the Project was probably not the best rock choice for a jazz festival. No matter, Wein needn’t have bothered because many in the audience headed for the refreshment area or out of the gates entirely.

Pianist Bill Evans, with drummer Jo Jones behind him emphasized the contrapuntal. Miles Davis closed the evening with several good moments, as did his tenor Wayne Shorter.

July 3

The afternoon was given over to big bands. Trumpeter Don Ellis’s 19-piece group featured an eight-man rhythm section: three bassists, four drummers, a pianist, and a mass of electronic equipment.

Odd-signature pieces were the specialty of the day, though the kind of music most of the weather-beaten audience wanted to hear. Ellis took his final bows before a few hundred people.

Still, Morgenstern, for one, was impressed, considering it an exceptionally well-drilled ensemble, an exciting band. The concert ended with a really BIG BAND, a 54-piece youth band from Massachusetts that played Basie, Goodman, Shaw, plus other compositions surprisingly well. Best of all, Balliett noted, were the glorious passages in which the brass section, 18 strong, opened up.

The evening concert was largely an extension of the previous evening’s tribute to Lionel Hampton. The opening acts: vibraphonist Red Norvo in a quartet setting (really needed?!); the Dave Brubeck Quartet showing more candlepower than usual (Balliett), Brubeck sounding better than he had in years (Goldblatt); jazz’s only opera singer Sarah Vaughan (according to Gary Giddins); and guitarist Wes Montgomery playing, at request, one of his breakout hits from the year before.

Goldblatt caught the moment: The audience danced in the aisles and stomped on their seats while Hamp and organist Milt Buckner hammed in a hilarious dance routine onstage as Jacquet kept wailing chorus after chorus. It was Hamp’s first appearance at Newport and the crowd let him know that it was a triumph.

Balliett was likewise impressed: Illinois went through his celebrated calisthenics, and it was like hearing Francis Scott Key sing the “Star-Spangled Banner.”

Time to go home.

Read my next blog for part 3 of my look back at jazz 50 years ago.

- Whitney Balliett, Collected Works: A Journal of Jazz, 1954–2001 (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2002), 272–24.

- Burt Goldblatt, Newport jazz Festival: The Illustrated History (New York: Dial Press, 1977), 130–39.

- Dan Morgenstern with Ira Gitler, “Newport ‘67,” DownBeat, August 10, 1967, 20–39.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed