BIG BAND

While Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Woody Herman, Thad Jones-Mel Lewis, and the Gerald Wilson aggregations continued to hold down the fort, two upstart bands led by Don Ellis and Buddy Rich rose to prominence.

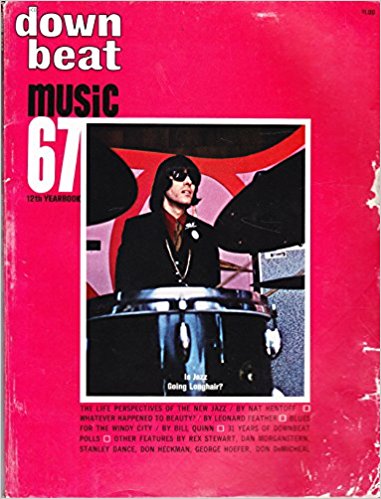

The exciting Ellis band featured unusual instrumentations and time signatures and polled fourth in the DownBeat readers’ Big Band category. Its leader, Don Ellis, came in forth in the Jazzman of the Year class.

Swing-era show drummer Buddy Rich powered his re-formed band to second place among big bands and took third place as Jazzman of the Year.

Bandleader and sax and flute player Charles Lloyd won Jazzman of the Year honors on the strength of his breakout the prior year, his highly publicized foreign trips, and popular Forest Flower album (Record of the Year, second place).

Don Ellis was the other new star. Besides fronting his well-rehearsed, rhythmically exciting band, he was acknowledged for his outstanding four-valve trumpet playing.

CLASSIC ALBUMS

Three members of the jazz pantheon—Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, and Sonny Rollins—released (close to, if not) their best albums: Miles Smiles, The Far East Suite, and East Broadway Rundown, respectively.

Sniping of the new music by DownBeat readers, critics, and musicians continued throughout the year. Yet there were signs of a growing acceptance. Based on his album reviews, poll positions, and festival invites, Ornette Coleman appeared to be assuming the role of the grand old man of free jazz.

Others, notably trombonist Roswell Rudd, seemed to be catching on, and the same could be said for the music as a whole, at least based on one metric: in 1967, 20 albums of the new music were reviewed in DownBeat, with an average four-star ranking. Not too shabby.

ROCK AND ROLL TREMORS

Rock rhythms were edging their way into jazz in 1967 (they had been for some time) and likewise into the pages of America’s premier jazz magazine, DownBeat. The magazine featured a four-page article on the Beatles that gave a decent history of the group, its influences, and concluded that the Fab Four were popularizers, not creators. Well, okay, creative popularizers.

Nonetheless, dear DB readers, you should have taken them (and their ilk) seriously. If the article didn’t grab their attention, then the seventh-place finish in the Record of the Year category for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band should have—the record lost out to Miles Davis, Charles Lloyd, Buddy Rich, and Duke Ellington.

JAZZ DEAD

Guitarist Gabor Szabo, who had been making some waves for himself with well-reviewed albums and meaningful club and festival dates, stunned the jazz world in a DownBeat article where he was quoted as saying. “Jazz as we’ve known it is dead.”

Putting aside exactly why Szabo made this remark, he later confirmed it, and the response from the jazz arts world was a resounding “no it isn’t.” (Harvey Siders, “Quotet,” DownBeat, November 16, 1967, 18.)

Every jazz person has things to carp about—inadequate pay, uncertainty about the status of their particular brand of jazz, lack of access to all forms of media, pressures from other more popular styles of music, on and on.

But true today, as it was in 1967, somewhere in the world at any given moment, there are people playing jazz in every conceivable style. Jazz as we’ve known it is still alive. See my recent July 2017 blog on the topic.

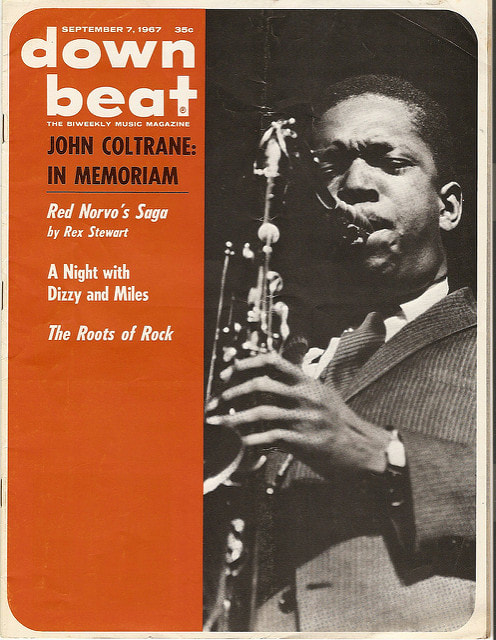

The year 1967 also saw the death of two prominent jazz deaths, John Coltrane (age 50) and Billy Strayhorn (age 52).

Read my next blog for part 2 of my look back at jazz 50 years ago.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed