So did the bebop masters of the 1940s: Dizzy Gillespie (trumpet), Stan Getz (tenor saxophone), J. J. Johnson (trombone), and Sonny Stitt (alto saxophone).

Of the several outstanding mainstream albums that year, two on the Verve label stand out. The first album brought swing-era trumpeters Roy Eldridge and Sweets Edison together with bebop trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie (four and a half stars, DownBeat), while the second paired bebop trombonist J. J. Johnson with the cool tenor saxophone of Stan Getz (five stars, DownBeat).

Beneath the mainstream and surface trends, other obscure musicians toiled according to their own lights to reinvigorate the music. In time, the jazz public would recognize musicians such as Charles Mingus (bass) and Cecil Taylor (piano).

JAZZ COVERS BROADWAY

In 1958, jazz players discovered Broadway and Hollywood musicals in a big way. More jazz versions of shows appeared in record stores that year than any other year before or since. To be sure, jazz musicians had plumbed show tunes since the very beginning of the Great White Way, but they had never devoted an entire album to the tunes from a single show until the late 1950s.

It all began with the surprise smash recording in late 1957 of a jazz version of My Fair Lady by Andre Previn (piano), Shelly Manne (drums), and Leroy Vinnegar (bass) on Contemporary. A classically trained and noted writer of film scores, Previn was a surprisingly good jazz pianist—Bud Powell (sort of) with a romantic tinge.

Previn later conducted the Pittsburgh and other symphony orchestras, but in 1958 he was the star of the best-selling jazz record in history, surpassing the previous top seller, Brubeck’s Jazz Goes to College recorded in 1954. Previn’s My Fair Lady was at the top of the monthly jazz charts all through 1958, falling no lower than fourth.

Although it was eventually surpassed in sales by Miles Davis’s Columbia recordings, My Fair Lady astonished the recording industry. The tuneful score and the popularity of the stage play and movie helped, as did the tasteful drumming of Shelly Manne, but the album’s smash status was well deserved; a darn good jazz trio record (five stars, DownBeat).

Understandably, a rash of similar recordings followed. Previn/Manne released four other show tune albums--Li’l Abner and Gigi in 1958, followed by Pal Joey and West Side Story.

Then came the onslaught: Gigi again (Shorty Rogers), Kismet (Mastersounds), The Music Man (Jimmy Giuffre), Porgy and Bess (Miles Davis), South Pacific twice (Chico Hamilton and Tony Scott), West Side Story twice (Manny Album and Oscar Peterson), and a host of other Broadway albums recorded by the Australian Jazz Quartet, Dick Marx, and others.

Every year has its fads, and this one belonged to 1958.

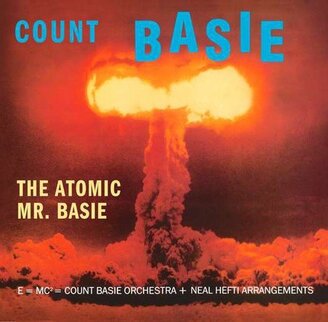

THE ATOMIC MR. BASIE

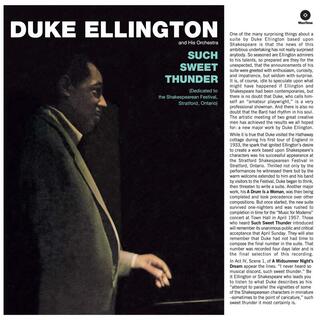

On top of everything else that happened in 1958, after a near decade-long decline, big bands surged back to popularity on the brass of the Count Basie and Duke Ellington orchestras.

Duke’s resurrection (he almost disbanded his orchestra of three decades in 1955) occurred around midnight on July 7, 1956, at the Newport Jazz Festival when Paul Gonsalves (tenor saxophone) took twenty-seven driving choruses on “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue,” causing a near rhythm riot among the 10,000 people in attendance.

Captured on vinyl by Columbia, the Newport recording received five stars in DownBeat.

The event was magical, almost mystical, a 1950s Woodstock that catapulted Duke and his band into the national limelight. Within weeks Duke was on the cover of Time, and whenever he was asked his age in later years, he would say only, “I was born in 1956 at the Newport Jazz Festival.”

In 1958, in the midst of his revival, Duke and his band toured Europe for the first time in eight years. The following year saw several more Ellington compositions and his first major film score for Anatomy of a Murder.

Duke was back! And so was the Count!

Basie’s comeback, unlike Duke’s, was not mercurial. After reforming his big band in 1953, his popularity steadily grew on the strength of hits such as “April in Paris,” with its “one more once” tag ending; and also “Shiny Stockings,” “Corner Pocket,” “Everyday and Alright, Okay, You Win,” the latter two with vocals by blues singer Joe Williams.

This album, the first of 20 on the Roulette label, and many say the best (DownBeat said four-and-a-half stars at the time), featured tunes written by a single arranger, Neal Hefti. Three of the tunes, “The Kid from Redbank,” “Whirly Bird,” and “Li’L Darlin’,” became staples in the Basie book for years after.

The Atomic band of 1958 was a powerhouse of talent to rival any band in jazz history, including Basie’s classic Kansas City band of the late 1930s.

This band exhibited ensemble power, precision, discipline, and dynamic control rather than the freewheeling, barrier-breaking soloists of the classic late-1930s Basie band. The Count himself said, “I have never bragged on anything, but the band I had [in 1958] was one I could have bragged on.”

Basie followed the successful Atomic with an album entitled Basie plays Hefti. He also benefited by Sing a Song of Basie, the sleeper LP of the year by the vocal group Lambert, Hendricks and Ross. LHR took scat singing to new heights by vocalizing meaningful lyrics to Basie tunes, ensemble passages and solos alike.

This record garnered a five-star DownBeat award and further heightened interest in the band. It came as no surprise, then, when DownBeat readers voted Count Basie and Miles Davis Jazz Personalities of the Year and elected Basie into the magazine’s Hall of Fame.

While other big bands languished in 1958—Stan Kenton’s, for example—the success of the two premier big bands paved the way for a general big band revival in the early 1960s.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed