Hartman is a great singer, beloved of fans, critics, and, perhaps, more importantly, entire generations of singers, most of whom have never heard more than six tracks by him [from the Coltrane& Hartman masterpiece album].[1]

Another happy accident took place on that date as well. On the ride out from Manhattan to Rudy Van Gelder’s studios in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, to record the six planned selections, the driver turned the car radio on, and there was the voice of Nat King Cole singing Billy Strayhorn’s “Lush Life.”

Upon hearing the song, Hartman exclaimed, “Man! This is one of the great tunes of all time.”

Coltrane responded, “Do you know it?”

He did.

“Lush Life” was the second tune recorded that day, and not surprisingly, it was a classic, an archetypical reading that used the Cole version as a template in terms of tempo and overall format.[3]

John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman became the one recording that exposed the most people to Strayhorn’s lovely song, all because the car radio was tuned to the right station.

CODA

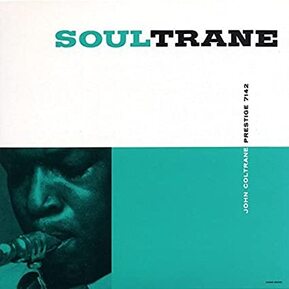

Coltrane certainly knew “Lush Life”—he had recorded an instrumental version for Prestige in January, 1958, released on his album Lush Life three years later.

- Will Frieidwald, The Great Jazz and Pop Vocal Albums (New York: Pantheon Books, 2017), 163.

- Edward Allan Faine, Serendipity Doo-Dah: True Stories of Happy Musical Accidents (Takoma Park, MD: IM Press, 2017), 75–6.

- Will Friedwald, The Great Albums, 166–7.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed