At various times during its history, jazz has surfaced to broad public awareness. The late 1950s was such a time, especially for jazz vocalists such as Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, and the Four Freshmen.

It is difficult to imagine today that Frank Sinatra was the premier male jazz singer of the 1950s. The 1950s Sinatra is not to be compared with the later Sinatra of Las Vegas, “My Way,” and “New York, New York” fame, just as the 1960s Louis Armstrong of “Hello Dolly” fame is not to be compared with the 1920s Armstrong.

Between 1954 and 1961, Sinatra recorded a series of classic LPs for Capitol with orchestrations mostly by Nelson Riddle or Billy May.

These recordings, now collected on 15 CDs, rank among the great musical works of the American 20th century along with the Armstrong Hot Fives and Sevens of the 1920s and the Miles Davis recordings of the 1950s. No male singer before or since has ever interpreted the classic Broadway and Hollywood tunes of the 1930s and 1940s—the so-called standards—with such sensitivity and swing.

Sinatra influenced jazzmen like no other singer before or since. When he recorded a song, it soon entered the jazz repertoire, that of Miles Davis, for example. During this period, Sinatra never compromised his musical integrity by playing down to the public, and he thereby brought jazz to a wider audience.

In 1958 Sinatra added the joyful Come Fly with Me and Come Dance with Me albums and the somber Only the Lonely to the classic Capitol series. Each record received rave reviews and sold very well.

Once again, DownBeat readers and critics voted Sinatra Top Male Jazz Vocalist, a position he held longer than any other male singer. Disc jockeys voted Sinatra’s singles “Witchcraft” and “All the Way” Best Songs of the Year.

No doubt about it, Sinatra was at his peak in 1958, as popular with the public as with the specialized jazz audience.

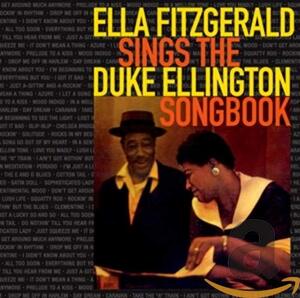

At the same time, Ella Fitzgerald had been recording a series of composer songbooks for the Verve label, interpreting the works of Harold Arlen, Irving Berlin, Cole Porter, Johnny Mercer, and Rodgers and Hart.

As usual, she won the Top Female Jazz vocalist in DownBeat, an honor she held for eighteen straight years. During her career, she also won eleven Grammys, more than any other female jazz singer.

Other female singers also were on the scene in 1958. Cool jazz singers Chris Conner, June Christy, and Julie London all had sizeable popular followings. Anita O’Day, with several mid-1950s recordings on Verve, was featured at the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival—a sign of her successful comeback.

New jazz singers Nina Simone and Mose Allison were heard on jazz radio programs and some juke boxes but had not yet made their marks with the general public.

Significantly, 1958 was the year of Billie Holiday’s last two studio recordings, both with orchestrator Ray Ellis. The first, Lady in Satin, was reported to be one of Holiday’s favorites but received mixed reviews from critics. The DownBeat reviewer, struck by the album’s bittersweet qualities—the life-worn voice of Holiday against lush strings—awarded it five stars.

Others criticized the incongruity of the lush musical setting for her croaking voice. Whatever the ultimate judgment of the Holiday/Ellis recordings, they represent the last testament of one of the greatest singers jazz has ever known.

INSTRUMENTALISTS NOT FAR BEHIND

Jazz instrumentalists had broken through to the general public as well. Dave Brubeck’s name was almost synonymous with jazz in 1958. He rode the crest of the West Coast wave higher and farther than any other jazzman and, in the end, transcended the genre.

His rather unique quartet that contrasted his full, bombastic piano with the dry martini sound of Paul Desmond’s alto, along with his popularity on college campuses and the backing of Columbia, all contributed to his success.

A surprise success with the public was the Modern Jazz Quartet: John Lewis (piano), Milt Jackson (vibes), Percy Heath (bass), and Connie Kay (drums). They played formal arrangements of classical music forms—fugues, concertos, and the like—and dressed in concert-hall attire.

But when they wanted to, they swung harder than any other group around. Arrangements aside, they were a swinging bebop group that endeared themselves to fans and critics alike.

The MJQ won both the readers and critics DownBeat polls for Best Combo in 1958. Nonetheless, jazz purists roundly criticized them for taking on airs of classical musicians and pandering to concert hall audiences. This was mostly a matter of appearances, however. The MJQ swung!

And in time, the quartet became the longest-running musical group with no personnel changes in jazz history.

One issue the author may wish to address comes in part 8 regarding the Modern Jazz Quartet. He writes, "And in time, the quartet became the longest-running musical group with no personnel changes in jazz history." The group did have an early personnel change, from Kenny Clarke to Connie Kay on drums. I’m sure the author knows this and means that AFTER that change, they were the longest-running group with no changes, but he might want to make that clearer.

Jonah Jones, a swing-era trumpeter and the Herb Alpert of his day, struck gold by playing a happy, easy-listening brand of jazz. George Shearing, an accomplished pianist, found public acceptance through his quintet’s smooth blend of piano, vibes, and guitar.

The sound was easy and melodious, with Shearing keeping his piano solos to a minimum. Both Jones and Shearing recorded for Capitol, a company with deep pockets to rival Columbia.

Towards the end of 1958, the small Chicago label Argo released But Not for Me, by pianist Ahmad Jamal, which became an instant hit with the public. Jamal, known to jazz musicians and revered by Miles Davis, had a spare brand of swinging jazz that the critics labeled “cocktail piano.”

The album received only two and half stars in DownBeat but the airwaves carried several tracks from the album, most notably “Poinciana.” Jamal’s version of this tune remains definitive.

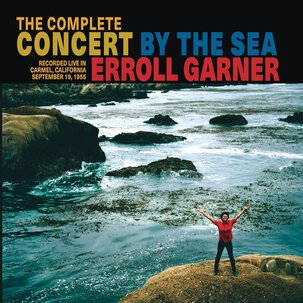

There is not a piano player alive who doesn’t either quote from the Jamal treatment when playing the song or botches his own version because Jamal’s version is so overwhelming. Jamal went on to prove his jazz mettle to critics and enjoys a reputation today as a singular stylist in the mold of Erroll Garner.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed