Gary Burton

The vibist’s two-handed, four-mallet approach spun soft, dreamy aural chords that separated him from his forebears on the instrument: Lionel Hampton, Red Norvo, Milt Jackson, and Bobby Hutcherson.

Conceptually, Burton chose to synthesize jazz and rock (even country at times), becoming one of the first jazz players to do so, though not as aggressively as later groups Miles Davis, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Mwandishi, Return to Forever, Lifetime, and Weather Report, giving these Johnny-come-lately outfits permission to use rock beats and distorted guitar in a jazz performance.

The guitarist on Tong Funeral is rising star Larry Coryell. Overall, the album comes across like a soundtrack to a theatrical performance, no doubt influenced by pianist Carla Bley, who would later expand on this construct in her epic Escalator over the Hill (1971).

Miles Davis

Both received top-rated reviews in DownBeat. The leader once again won top honors in the trumpet and combo categories in both the DownBeat critics and readers polls. Moreover, the trumpeter’s frontline star players also issued notable albums of their own.

Wayne Shorter

With this release, the idea began to build in the jazz community that Shorter was much more than a soloist—indeed, a composer of merit likely to join the ranks of John Lewis, Charles Mingus, and Duke Ellington.

Herbie Hancock

Today, however, this album with its interesting, simple melody sound clouds has gained an appreciative audience. Another way to put it: Miles Davis had his Birth of the Cool, and Herbie had his Speak Like a Child.

Duke Ellington

Far East Suite is my number one favorite, And His Mother, featuring all Strayhorn tunes, is my number two. In my opinion, Duke’s mid-1960s band is the equal of the maestro’s famed late ’30s/early ’40s Webster-Blanton band and deserves a name unto itself. Perhaps Ellington’s Second Testament band? Nope, that name’s taken by the Basie aggregation.

The reason why it’s so difficult to come up with a proper moniker is that it had not one or two but numerous outstanding soloists at or near their peak: Paul Gonsalves (tenor), Johnny Hodges (alto), Harry Carney (baritone), Jimmy Hamilton (clarinet), Cootie Williams (trumpet), Rufus Jones (drums), and, of course, Duke Ellington (piano). Band nickname aside, And His Mother is the Ellington ’60s band at its peak—the same could be said for altoist Johnny Hodges.

As Nelson Riddle was to Frank Sinatra and as Lester Young was to Billy Holiday, Billy Strayhorn was to Johnny Hodges. Stray’s compositions brought out that special, sensuous Hodges sound. As singer/author Lillian Terry recently put in her book Dizzy, Duke, Brother Ray, and Friends, “Heavens, when he blows those long, languid notes . . . it’s an actual caress!”

Yes—as on Hodges’s tribute to Strayhorn on “Blood Count,” “After All,” and “Day Dream,” the latter a late-at-night, sob-in-your beer favorite. The flip side of the Hodges coin—the bluesy side—Billy knew all too well, as illustrated on “Snibor,” “The Intimacy of the Blues,” and “Acht O’Clock Rock.”

Buddy Rich

Don Ellis

Other critics heard it differently and did not characterize the band as exciting. Magazine subscribers sided with Siders.

Rahsan Roland Kirk

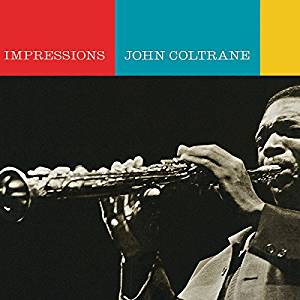

John Coltrane

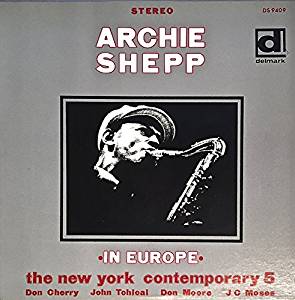

Two of Coltrane’s albums, the now classic Impressions and Om, were reviewed in DownBeat in 1968; the former received five stars, the latter four. The torchbearers, the tenor men closest to him stylistically and personally, forged ahead with new albums: Albert Ayler (In Greenwich Village), Pharoah Sanders (Tauhid), and Archie Shepp (In Europe).

Aretha Franklin

In my book Serendipity Doo-Dah Book One, I included a short piece on Ms. Franklin, covering her rise to prominence when she switched to Atlantic Records in 1967 and her recovery from her mid-career slump in 1977. Read it here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed